Bodies are innately fascinating. We’re curious to see the bodies of others because we long to understand more about being human, as if another’s nakedness will disclose information and revelations we can’t ascertain otherwise. Inevitably, this ongoing fascination has been reflected and codified throughout the history of art, where the nude continues to appear in so many varied guises and forms.

From the physique photography of muscled male torsos deftly dodging censorship laws from a time when homosexuality was criminalised, to portraits of young women in naked, unguarded moments in their bedrooms, and a husband’s obsessive photographic study of his vivacious wife, we have gathered ten of the best photo stories considering the body published on AnOther over the past year.

Geography by Zora Sicher

Spanning 14 years of prolific image-making, right from her earliest foray into photography, aged 16, Zora Sicher’s photo book Geography navigates her archive of tender, raw portraiture. The Brooklyn-born photographer has a relationship with everyone who appears in the book, which perhaps accounts for the unguarded, intensely intimate quality of her portraits. “The book is a mapping of time, bodies and spaces,” she told AnOther. “There’s no fashion work in here, there are no hired models, it’s all people that I was very close to, or am very close to.”

Gilded Lilies by Steph Wilson

During a feverish fortnight in this year’s springtime heatwave, Steph Wilson shot a series of portraits of her friends adorned with very little but their most treasured pieces of jewellery. Taking inspiration from Peter Hujar’s 2025 retrospective at Raven Row, her guiding principle was to create a series of images echoing the weight and gravitas of Hujar’s work. Wilson photographed people from her creative milieu, selecting artist and maker friends she felt had a particularly heightened relationship with objects, including Harley Weir, Elsa Rouy, Charles Jeffrey, Michaela Stark, Michael James Fox and George Rouy, among many others. The mood of Gilded Lilies is intimate, reflective and dense with mystery; just her sitters and their chosen jewellery with what Wilson describes as its fascinating potential to keep “our secrets well after we’re dead”.

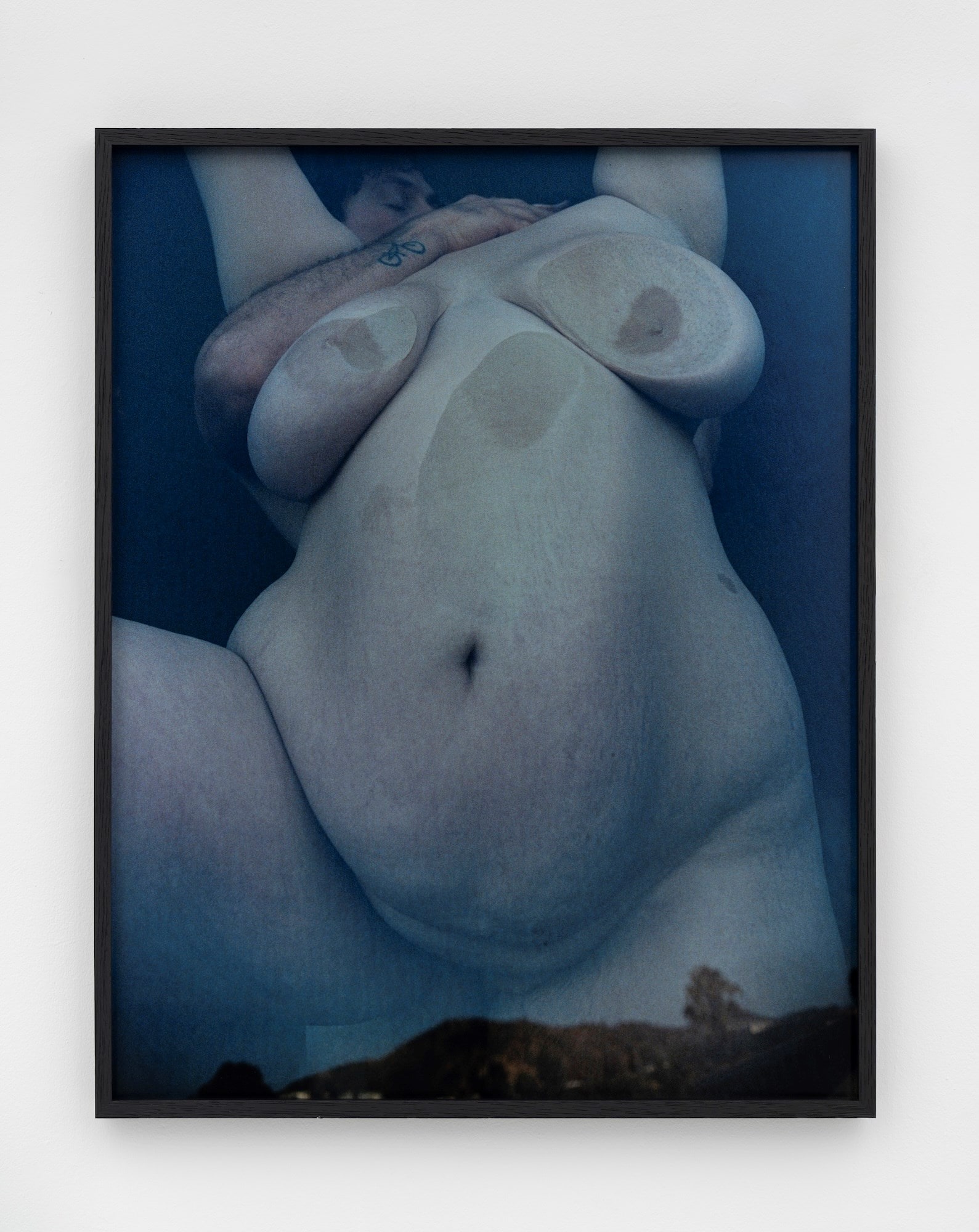

Blue Hour by Senta Simond

As a photographer who so often explores the feminine figure as both subject and object, Senta Simond turns her enquiring lens on her partner, model Leon Dame, in this series of tender portraits. “I was never really interested in photographing men before, but because of him, I started to look more at the male figure in photography,” the Swiss-born photographer told AnOther. Blue Hour is interspersed with totemic symbols of masculinity – torn denim, white briefs, the sleek bonnet of a car – yet the portraits are shot through with the intense intimacy of a lovers’ collaboration, and by Dame’s unique presence. “He’s very bodily,” she explained, “he really knows how to inhabit himself, like a dancer sometimes. It can be something very emotional.”

Small Death by Martha Naranjo Sandoval

For Martha Naranjo Sandoval, taking pictures is an act of love, inherited from her father who worshipped her with his camera as a child in Mexico City. Emigrating to New York in 2014, Naranjo Sandoval has been assembling the vast archive of images which she dreamed would one day become her first photo book. Her debut monograph, Small Death, has been carefully selected from an archive of over 50 rolls of film shot during these years, throughout which her experience of being an immigrant in America, forging a new life in a new city, and inhabiting her body have been inscribed and explicated with tremendous beauty and compassion.

Rooms by Greta Ilieva

Greta Ilieva uses her camera to explicate the world around her. Growing up between London and Bulgaria, her childhood was bohemian, and nudity was a natural part of life with her photographer mother. Through her own practice, she began contemplating the more private relationships women have with their bodies – the memories and emotions they carry, how we inhabit our bodies when we’re unobserved. Ilieva’s series of portraits of women naked in their bedrooms investigates these questions. Though the sitters are the subjects of this inquiry, the pictures feel intimate and natural; we don’t feel we are intruding on their privacy as much as being invited into it. The portraits are interspersed with photographs of the women’s beds – unmade and uninhabited, and there’s something almost as intimate about the contours of their sheets and pillows as the contours of their bodies.

Echo by Guen Fiore

The concept of beauty has always occupied Guen Fiore. Growing up in Italy, she felt conscious of not fitting into what she perceived as the beauty ideal, which made her even more curious about transgressing its confines. Echo brings together portraits of women aged 17 to 24 whom the self-taught photographer scouted on Instagram, drawn to each sitter for the way they presented themselves with supreme confidence. “Someone told me that these girls somehow remind them of me, so there’s probably been a lot of mirroring,” Fiore told AnOther. “Maybe photography has helped me see the beauty in those girls, which helped me to see beauty in myself as well, which I have always struggled with.”

The Garden by Harley Weir

Gardens have always been potent symbols of beauty, desire and temptation. For Harley Weir, they have a complicated dual nature. Earlier this year, the acclaimed artist took over two floors of Hannah Barry gallery in south London for her exhibition, The Garden. One floor was devoted to enshrining memories of her adolescence – new works collaging old secret notes from friends at school, cuttings from teen magazines, dried flowers. The lower floor looks toward the second major shift in women’s lives – the mid-thirties onwards, when girlhood evaporates and women are socialised to believe their desirability and visibility begin their descent. This is the second coming of age, and Weir’s works on paper – at times horrifying, often disarming, always beautiful – explore childbirth, the decline of one’s parents, hormones, egg freezing, blood and blowjobs.

Yoko by Masahisa Fukase

Masahisa Fukase’s obsession with his wife, Yoko Miyoshi, is chronicled in Yoko, a photo book which brings together a collection of incessant portraits. Originally published in 1978, 15 years after the pair met, the pictures show a stormy, passionate romance which continued to dominate both their lives long after their marriage had ended. Among the spirited portraits of Yoko dancing on a tabletop, laughing with armfuls of cats, or lying prone and naked with only a crab covering her crotch, there’s also a sense of growing resentment from Fukase’s muse. “In the ten years that we lived together, he only looked at me through the lens of a camera, and the photographs he took of me were unmistakably depictions of himself,” she complained.

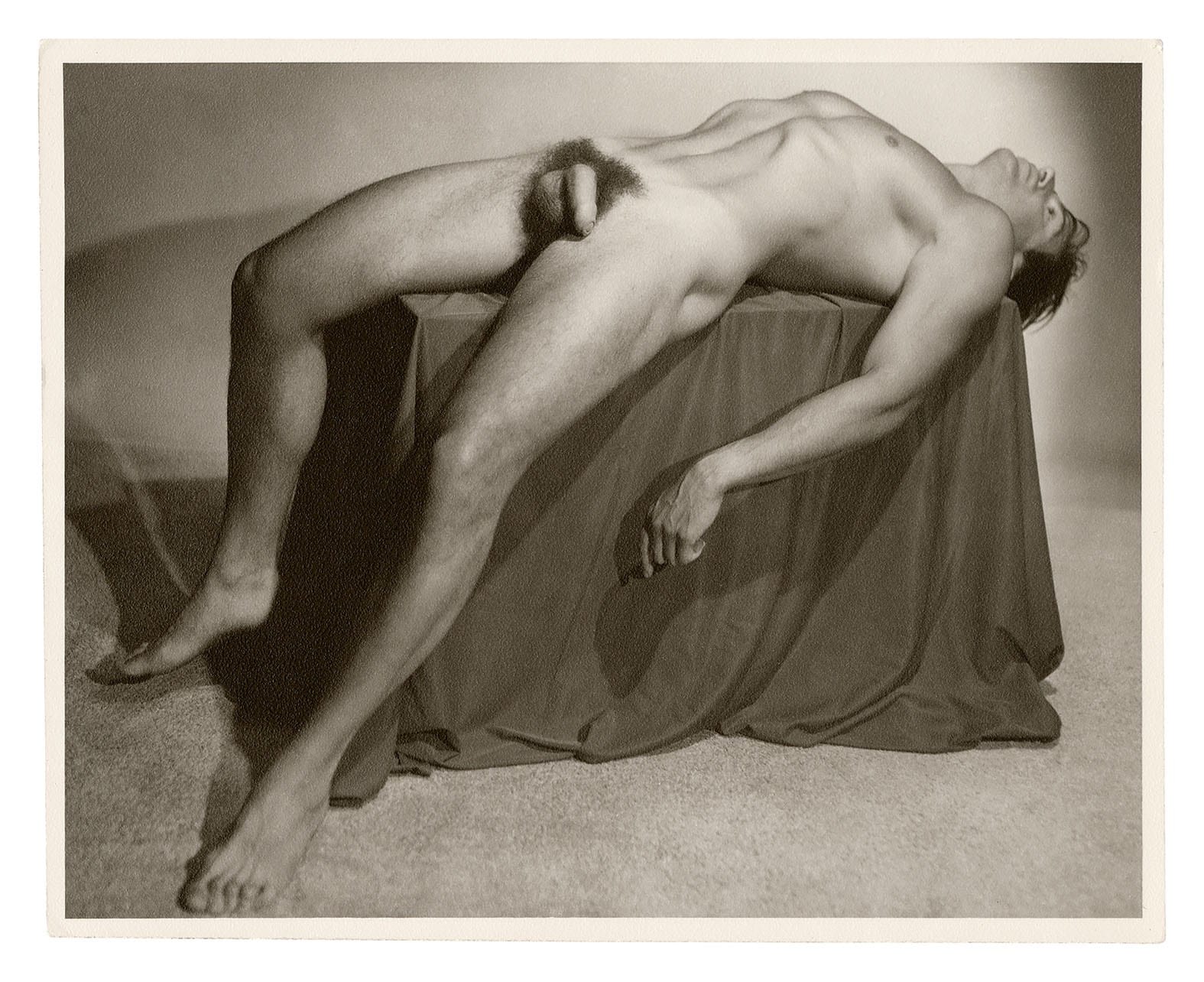

Physique by Vince Aletti

Edited by renowned critic, collector and curator Vince Aletti, Physique is a magnificent collection of over 250 photographic prints that reinstate the male nude to a classical ideal. Shot predominantly in the 1940s, 50s and 60s, when homosexuality and the depiction of male frontal nudity were criminalised, this style of homoerotic portraiture was created under the guise of “health and fitness”. For Aletti, there’s an appeal to the more ambiguous, less explicit photography of this earlier era. “After physique, the penis became the main focus of everything. It’s less refined. It doesn’t need classical styling, just a guy with a big dick,” Aletti told AnOther. “Physique was a response to restrictions and laws that kept photographers on a short leash, and what made it lively was they were constantly pulling at that leash.”

No Shows by Nick Offord

The waiting around and hanging about that is endemic to life as a model at fashion week afforded Nick Offord plenty of opportunity to take pictures of himself and the model friends he made during these years. No Shows collects his photographs of life on the road, going to castings, travelling to shows and killing time in budget hotel rooms. In contrast to their poised performances on the catwalk, the young men in Offord’s portraits are languid and relaxed, lounging semi-naked on their beds, leaning from hotel windows in their underwear, prone and shirtless on cushions with cigarettes dangling from their lips. One picture shows a close-up of bare feet with bloodied, bandaged heels exposed – a glimpse at the real bodies behind the glamorous illusion of fashion.