After nearly half a century, the Japanese artist’s classic book has been republished, offering a fresh take on one of photography’s greatest love stories

Not since his passing in 2012 has Masahisa Fukase drawn as much attention as he has this year. The depiction of the photographer’s life on the big screen in Mark Gill’s biopic Ravens coincides with the reissuing of two masterpieces for the first time in nearly half a century. Homo Ludens was originally published in 1971, while Yoko came in 1978, 15 years after Fukase met the love of his life to whom he dedicated this book. Yoko Miyoshi has herself played a hand in the conception of the reprint, while publisher Akaaka has revived the original with an upscale and fresh, contemporary cover.

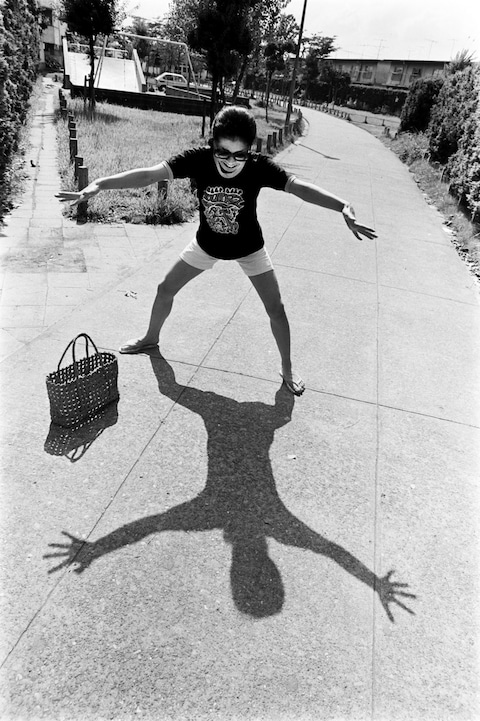

“He, Fukase, appeared before me on a hazy spring day,” recalled Yoko. “He had a buzz cut, swayed his hair right to left as he walked, and wore a baggy crimson polo shirt. My cheeks glowed with the freshness of youth and I spent my days completely unfamiliar with facial packs and other such beauty treatments.” She also had no idea the world was actually full of people called photographers. But she soon become the main subject of one, striking impossibly elegant poses in a slaughterhouse while rocking bright white lipstick. The opening pages of Yoko throw off all kinds of sparks, chronicling the young couple’s life together, as they fell in love, got married and moved into a new danchi complex in Soka, which was a place of dreams for them and their two cats.

As you leaf through the book, images collide and unveil the spirit of their bond – defiant, fierce and fun – all the while evoking the gentle thrums of time. The mundane meets the theatrical, from fortune papers and New Year’s snow to dancing on the kitchen worktop naked. The bulk of their time is spent in and around Tokyo, but there are also snapshots of their travels to their respective birthplaces. One chapter lingers in 1974 New York, where Fukase’s works were included in the New Japanese Photography exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. Here, Yoko is pictured kneeling beneath her own portrait, and later, billowing on Montauk Beach, as if the gusts might blow her away. The book’s high point is the series of ritualistic window shots Fukase took of Yoko leaving for work every morning. Sequenced in quick succession, they echo the photographer’s quiet desperation, an increasingly anxious desire to capture every last bit of her – trophy photos in case she never came home.

“In the ten years that we lived together, he only looked at me through the lens of a camera, and the photographs he took of me were unmistakably depictions of himself,” said Yoko, who went on to dub her husband an “incurable egoist”. Often levelled at Fukase is the notion that he obsessively photographed Yoko as a way of plumbing the depths of his own being, but, then again, who doesn’t photograph to find themselves? In any case, it is hard to imagine any situation in which Yoko would not find her image warped through the glass of Fukase’s camera, which was indeed more like a mirror. For all the glee Yoko exhibits from the attention – often stoking up Fukase’s fire – she became increasingly suffocated by his unrelenting gaze, and the performative pressures that come from a muse-artist relationship. She once described their marriage as “moments of suffocating dullness interspersed by violent and near suicidal flashes of excitement.”

Through the 60s and early 70s, the couple partied, drank, fought, broke up, reconciled and fought again. Fukase had numerous affairs, and Yoko had other lovers too. Feeling like their marriage had reached a tipping point, Yoko filed for divorce in 1976. Fukase made the lonely journey to Hokkaido, his birthplace, where he would ceaselessly chase ravens over the next decade. The book’s closing image is of a raven whose gloomy shadow seems to engulf the lovers’ intertwined fates. Fukase subsequently careened into a crippling depression, and just before his 60th birthday in 1992, he tumbled down the stairs of his favourite Tokyo haunt and entered a coma that would last 20 years. Yoko visited him every month throughout his long limbo, though, heartbreakingly, he was unaware of her presence. “With a camera in front of his eye, he could see, not without,” she said.

It is clear that Fukase remains part of Yoko’s identity. “At first, there were a few photographs I wished not to be included in this reprint,” Yoko writes in her closing text. “But let me say that out of respect for Fukase’s intentions, it was decided that the reprint would retain the composition of the original.” She concludes with a touching thought. “If Fukase were still alive today and I could say one thing to him now, it would be, ‘Well, it is what it is, right!’”

These photographs have become heavier with the weight of time and human destiny, especially given the photographer’s end. Yet the renewed lease of life this collection bestows is a reminder that it is not photographs that change, but our relationships with them. All these years later, what these euphoric, doomed lovers gift us once more is a sublime, heartfelt tale of what it means to love another person, and to live photography to the max.

Yoko by Masahisa Fukase is published by Akaaka, and is out now.