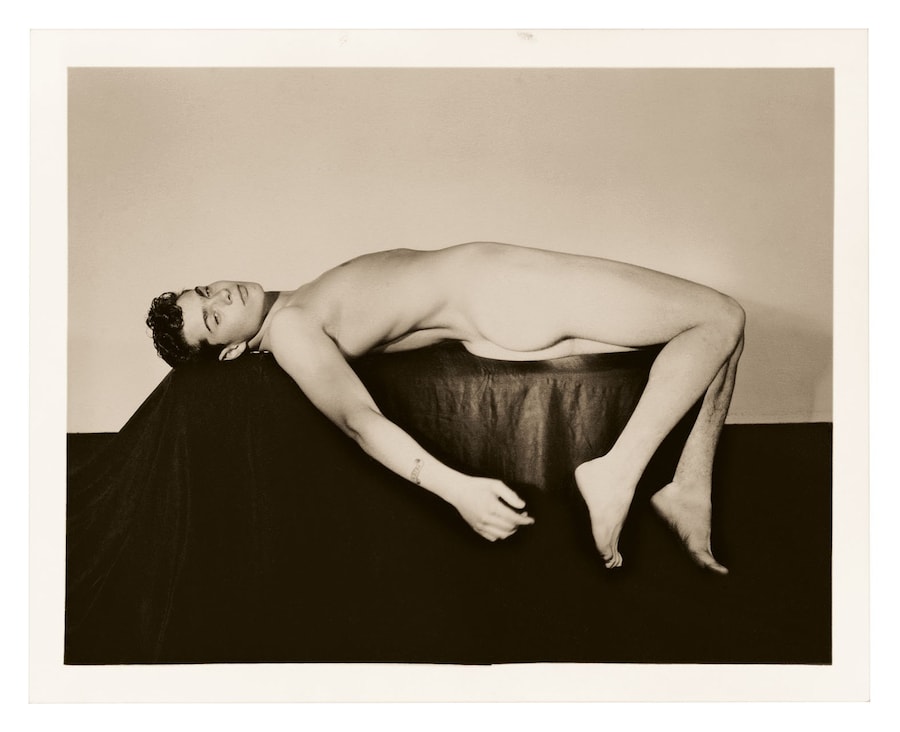

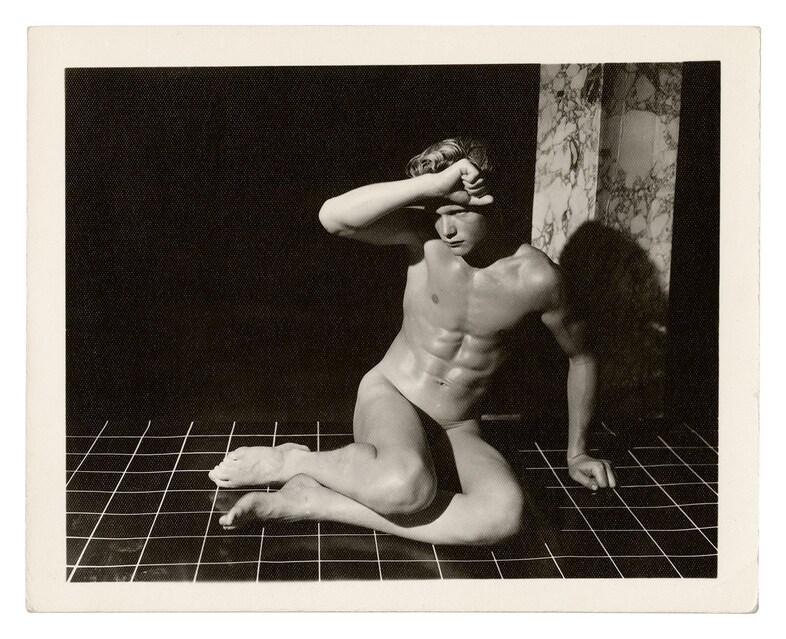

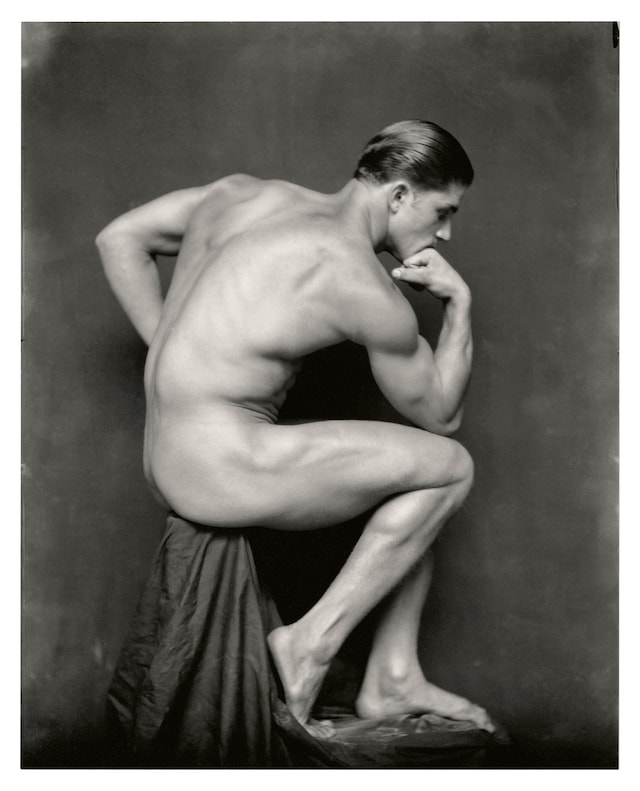

The photo critic’s latest book, Physique, is a sumptuous collection of homoerotic American physique photography from the 20th century

As the first journalist to write about disco in 1973, Vince Aletti has been a seminal force in queer culture for over half a century. Now the renowned critic, collector and curator returns with Physique, a sumptuous collection of more than 250 rare physique photography prints that restore the male nude to the realm of fine art. Created at a time when both homosexuality and the depiction of male frontal nudity were criminalised, physique photography deftly combined America’s twin obsessions with fitness and hypermasculinity to market and sell Grade-A beefcake to the public. But within these risqué images of masculine prowess preening with delight lay a love that dared not speak its name while cavorting in plain sight.

In retrospect, it is hard to imagine these titillating photographs by luminaries like Bob Mizer, Bruce Bellas (Bruce of Los Angeles), Lon Hanagan (Lon of New York), and Douglas Juleff (Douglas of Detroit) could have been seen as anything other than fabulously homoerotic art. But, as Aletti notes, we witnessed this same ecstatic embrace of Bruce Weber’s seminal ad campaigns for Calvin Klein and Abercrombie & Fitch during the 1980s, 90s and 00s. “Bruce Weber is the connecting point,” Aletti says. “I was excited that everybody wanted to look at his pictures but I was always puzzled by the incredible acceptance of that.”

But as Physique shows, the seeds of desire are planted in a return to the classics. Male nudity, once the provenance of Renaissance artists like Michelangelo, was reimagined as the classic Übermensch driven by the spirit of American exceptionalism. From the start, the United States, a postcolonial empire in search of a heroic past, embraced the tenets of ancient Greek iconography to create its own cast of masculine archetypes: the athlete, cowboy, sailor, biker, and blue-collar stiff. Most simply appeared as themselves: artists and models who knew how to sell a look and all it took was one simple, skimpy piece of cloth, the penis itself a bridge too far for pre-Stonewall picture magazines.

Providing cover under the guise of “health and fitness”, physique magazines mapped a new vision of the red-blooded American male just as bodybuilding became widely popular in the 50s and 60s. Here, bare flesh and rippling muscles are presented as aspirational, providing a safe space for gender affirmation and admiration among cisheterosexual circles who turned a blind eye to the act of seduction embedded in the photographs themselves.

Because of the political climate, many artists did not sign or stamp their work, while others referred only to the name of the studio. Aletti studied the images, identifying styles that set them apart, and cross-referenced them with the magazine ads they ran promoting their photography services, where discerning collectors could purchase private works for themselves. Aletti followed the trail of information back to Bob Mizer’s Athletic Model Guild, which published the Thousand Model Directory in 1957. The Catalogue, which was drawn from an archive of 35,000 photographs, provided readers an affordable array of pricing options.

“I thought of all these men in LA, photographing some naked person every day, sometimes 20 of them,” Aletti says. “When I saw the model directory, I thought, oh my God, this is sociological. These 1,000 men were all photographed by the same photographer, and that was just the beginning of his work. The number astonished me and made clear just how busy these studios were. They were constantly finding new models and turning out new work.”

Aletti first encountered physique magazines in a convenience store while summering with his family on the Jersey Shore. Then just eight or nine years old, he stood mesmerised at a picture of two teens, one slung over the other’s shoulders as a trophy. The photograph was captioned Victor and Vanquished, a campy wink to its older queer following. He remembers feeling excited and confused by the feelings they aroused, and later snuck copies of Tomorrow’s Man, Adonis, and Body Beautiful home as a teen. But it wasn’t until the 70s, after he moved to New York and became friends with Peter Hujar, that Aletti developed a deeper appreciation for the art form itself. He started frequenting Physique Memorabilia in the East Village, perusing stacks of vintage prints rendered by artists who understood the medium was the message

“At the beginning, I didn’t think of myself as collecting them but within a month or two, I had 100 [prints] because they were inexpensive, 4x5 prints for five dollars, 8x10 for ten,” Aletti says. “They were produced commercially in large numbers, but they’re not slick like film stills. They are done on beautiful paper and some of them are toned so there’s a sense that the photographer really cared about making a good picture. Many of them saw themselves as artists and they made work to be respected.”

Though physique magazines fell out of favour after obscenity laws were repealed during the wake Gay Liberation, their seductive blend of camp and classical aesthetics suddenly haplessly old-fashioned in a radical new age, their allure only deepening with the passage of time. At a time when porn encourages instant gratification, physique photography is the promise of a future waiting to be fulfilled. “After physique, the penis became the main focus of everything. It’s less refined. It doesn’t need classical styling, just a guy with a big dick,” Aletti says. “It became a different thing and the photographers didn’t have to think about what they were doing in the same way. Physique was a response to restrictions and laws that kept photographers on a short leash, and what made it lively was they were constantly pulling at that leash.”

Physique by Vince Aletti is published by SPBH Editions, and is out now.