Six years in the making, Julie Ha and Eugene Yi’s new documentary Free Chol Soo Lee exposes the racism of the American justice system in 1970s America

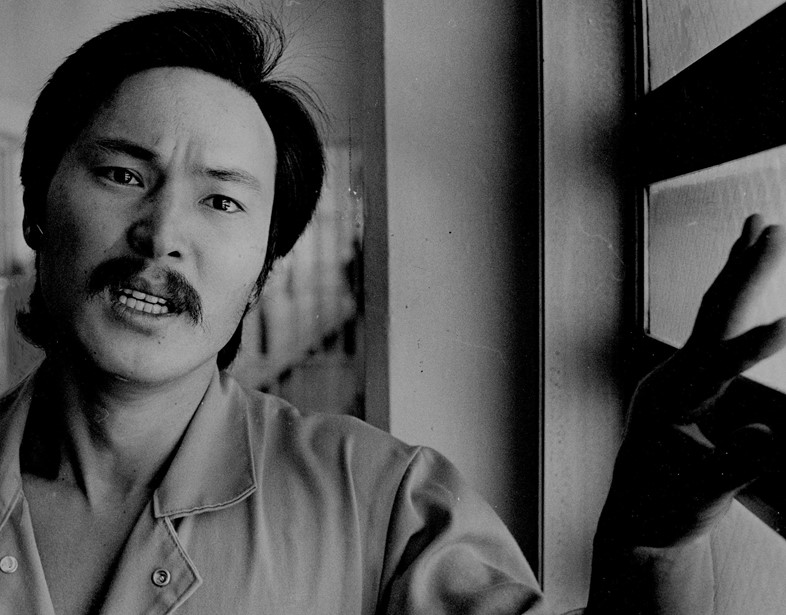

In 1984, journalist and producer Sandra Gin won an Emmy for an episode of public affairs programme Perceptions. The previous year, Chol Soo Lee (a Korean immigrant wrongfully imprisoned for a Chinatown gang murder in San Francisco) had been exonerated after spending a decade in prison – with four years on death row – and Gin’s programme sought to highlight this miscarriage of justice and the movement it galvanised. A clip from the show, titled A Question of Justice, opens Julie Ha and Eugene Yi’s new documentary, Free Chol Soo Lee. “I was not an angel on the outside, at the same time I was not the devil,” Lee tells Gin, setting the tone for Ha and Yi’s film, which continues following his life up until his death in 2014, aged 62.

Both filmmakers came to Lee’s story through KW Lee, a Korean-American investigative journalist working in Sacramento at the time of his imprisonment, who would go on to be a leading voice in the defence committee that ultimately established Lee’s innocence. “I was 18 and did an internship at a Korean-American newspaper that he had founded, actually inspired by Chol Soo,” recalls Ha. “It was mind-blowing to learn that there was a Korean immigrant who could be wrongfully convicted in our American justice system, and that it could be the work of a journalist – along with a movement led by Asian-Americans – to right this wrong. That changed my whole world.”

“Eugene and I had always been attracted to more complex Asian-American stories, and wanting to tell them with nuance and depth,” she continues. Free Chol Soo Lee is the pair’s first film, and was informed by timing – the magazine they worked at had shuttered – and a shared desire to continue this kind of storytelling. Having attended Lee’s funeral nine months earlier, Ha was further encouraged by a sense of generational responsibility. “I was struck by the feeling in that funeral space – a heaviness, something beyond grieving,” she explains. “At one point KW Lee stood up, almost angry. ‘Why is this story still underground? This landmark Asian-American social justice movement, why is it not known?’ He just knew this story and this history was hugely consequential and really singular.”

A six-year project, the filmmakers were adamant their work should be a complete survey, however uncomfortable. “That really was important,” says Yi, “to tell the full story of Chol Soo, and certainly it seemed like people were ready to talk about him and the way he affected them, with a candour that might have been difficult earlier.” Using archive footage, present-day interviews and animation, the film subsequently highlights the many lives Lee led, from the childhood trauma of attending a school geared towards Chinese-American kids, to the difficulties he faced adapting to life after prison, not only as a result of his incarceration but due to the celebrity he gained and the debt he felt as the face of a movement. Elsewhere the film unpacks the racism that led to Lee’s conviction – the earliest witnesses were all white tourists who mistook Lee for Chinese – and briefly references the 1989 film True Believer, a whitewashed retelling of Lee’s story that casts the Asian-American community as props.

Further underscoring the cruelty of these chapters is the Tower of Power song, You’re Still a Young Man. After it’s revealed that it played in the van that drove Lee to prison, the track is used intermittently as a vehicle for reflection, while Sebastian Yoon, a Korean-American with his own experiences of incarceration, humanises passages from Lee’s memoir as the narrator. “For a long time we felt this nagging insecurity that as much as we immersed ourselves in the words of Chol Soo, we still weren’t getting it all – and we wanted him to have agency. Once Sebastian joined, it felt like everything fell into place. He actually collaborated with us on the script,” notes Ha.

Central to the film and what guided the movement that fought for Lee’s freedom is a sense of community. For Yi and Ha, it also allowed space for a highly personal documentary with wonderful depth. “KW Lee opened a lot of doors in terms of introducing us to people who were involved,” says Yi. “What was fascinating was [that] everybody had something from that moment in their lives, because it was so important, everybody had a box. There’d be no film without this beautiful community archive.” Indeed, the film’s title itself adopts the chant that began as a bold protest and later became a cry of grief, heard at Lee’s funeral in recognition of the pain he carried throughout his life. “We realised we could allow this process of catharsis for the activists, just in the making of the film,” acknowledges Ha. “They had regrets, wishing they could have helped him more. They accomplished their mission of freeing him from prison, an incredible feat – maybe a legal precedent – but many felt they owed him more. That speaks to their tremendous depth of compassion and humanity.”

Free Chol Soo Lee is out now.