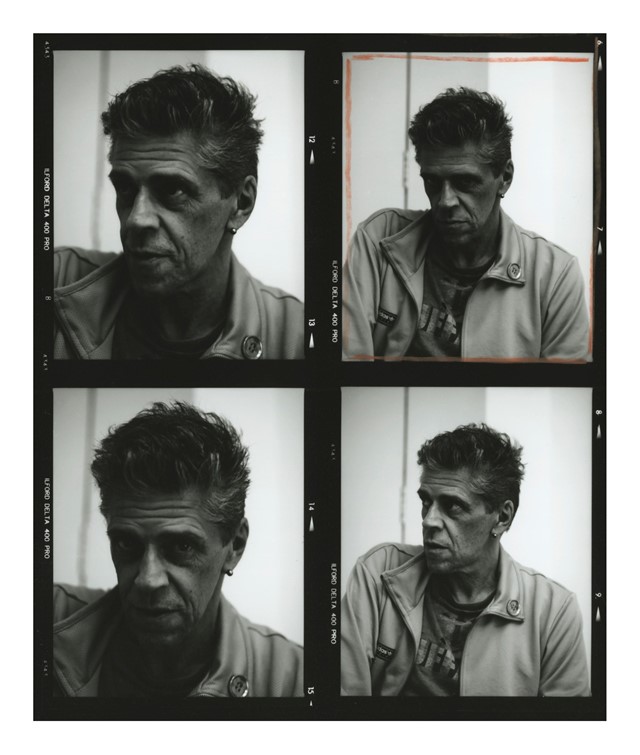

Today the fashion and art world mourns the loss of one of its truest radicals. Here, we pay tribute to his life and legacy

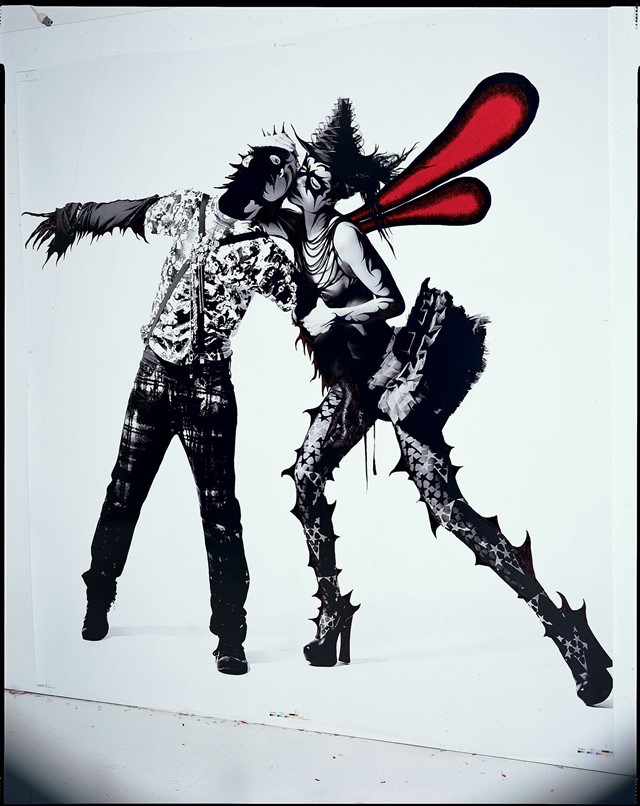

The dictionary definition of ‘Radical’ reads thus: 1. Especially of change or action, relating to or affecting the fundamental nature of something; far-reaching or thorough. 2. Characterised by departure from tradition; innovative or progressive. Today, the fashion and art world mourns the loss of one of its truest radicals, Judy Blame, who has passed away at the age of 58. Blame’s work in design, styling and art direction remains some of the most vital in counter-cultural history, instrumental in defining the decade of 1980s and beyond.

At the age of 17, Blame, né Chris Barnes, ran away from his home in Devon to London. It was here he met fellow Blitz Kid Scarlett Cannon and designer Anthony Price, who bestowed him with a new moniker. As Judy Blame, he would go on to become heavily involved in the New Romantic scene, with the club Heaven playing host to his and Cannon’s weekly night, Cha-Chas, attended by the likes of Leigh Bowery, Stephen Jones and Marilyn.

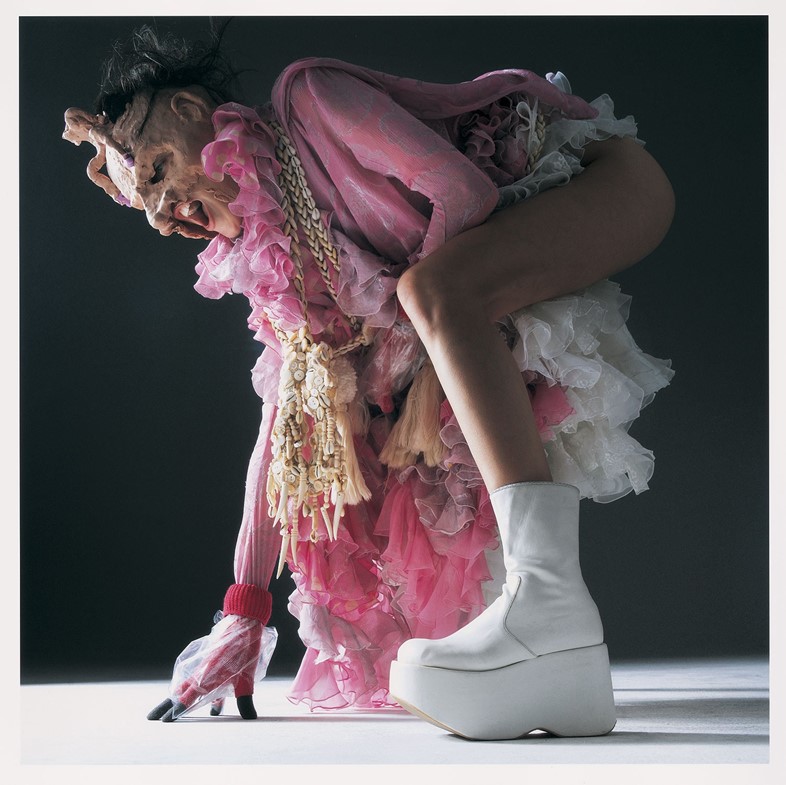

A few years prior, Blame would hand-make trinkets as gifts for his friends. One of the first he ever created was in 1974, a small safety pin threaded with six plastic beads in rainbow gradient – a metaphor for a young boy stuck in the countryside destined for a more colourful life, if ever there was one. “I suppose it’s the first accessory I thought of,” he said. As a new resident of London, Blame would mudlark in the River Thames, finding buttons, bones and more safety pins that would go on to form the basis of his pearly-punk design aesthetic.

During Thatcher’s Britain, Blame eschewed the gluttonous excesses of the era by utilising these found objects in jewellery. “One of the important things I’ve learned about the way I approach things is I always do a lot of my thinking and creating on instinct,” he told AnOther in 2013. “I don’t think that a diamond is better than a safety pin; to me it’s just a thing or a shape. Money isn’t a thing that holds back creative people. In fact, it can spoil it sometimes.”

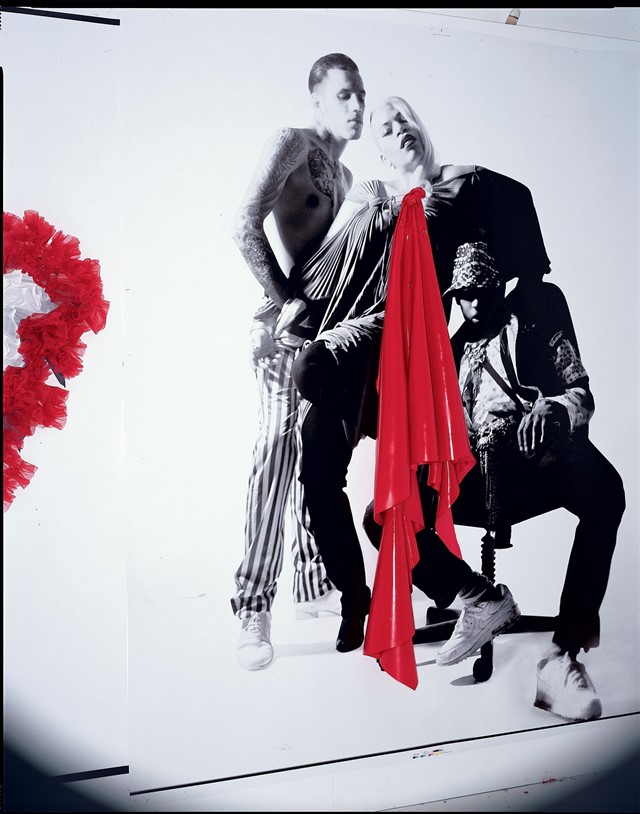

Through the music scene, the designer met the late Ray Petri. Petri headed up the Buffalo fashion collective, of which Blame would become a central figure, styling and art directing for The Face, i-D and Blitz under his friend’s encouragement. He dressed Boy George in “everything but the kitchen sink” for the 1984 Grammys, and created Neneh Cherry’s iconic Buffalo Stance look, in 1989. Blame also made an appearance in Cherry’s Manchild video, replete with signature Buffalo-esque gold chain and acid-green eye shadow. The two would remain life-long friends.

Blame is also renowned for co-founding the Dalston-based craft collective and shop The House of Beauty and Culture in 1985, alongside John Moore. Reportedly, after it opened, Martin Margiela visited the house himself, and was enamored. Helmut Lang has also cited Blame as one of his great influences. In the 1990s and 2000s, Blame would collaborate with the likes of Jeremy Scott at Moschino, Rei Kawukubo at Comme des Garçons and Kim Jones at Louis Vuitton. His legacy was solidified in a retrospective exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Arts two years ago – although, always the disrupter, Blame preferred to call it a ‘montage’, rather than the former.

Blame remained a prolific user of Instagram up until his death, where he shared archival and personal material, loved by his loyal followers. On the 22nd of February 2015 – almost two years to the day before he would leave this earth – he posted a prophetic handwritten note: “After years of trouble making – drug taking and experimenting with every part of my life, it seems the most radical thing you can do today is care for yourself and other people!” Judy Blame has gone too soon. But these parting words – alongside the legacy he leaves behind him – will remain forever apt.