“Cult is a word you would never say in Hollywood,” John Waters once said. “Cult means that [the film] lost money and three smart people liked it.” In London, where artists deign to veer away from the establishment and towards something altogether more avant-garde, Waters’ sentiment is the essence of the city’s most visceral creativity. It is central to the fabled story of House of Beauty and Culture, the little-known studio and shop that was furrowed away on Dalston’s Stamford Road from 1986 to 1989. Founded by shoe designer John Moore, HOBAC was the home of a collective of impecunious artists, designers and photographers – above all, craftsmen – that flipped the contents of London’s gutters and skips into highly stylised objets d’art, displayed in the cult East End retail space and cherished as tokens of rarity and status on the dancefloors of Taboo at a time when nightclubs were the social media, Internet and art world of their day.

A Post-Punk Resistance

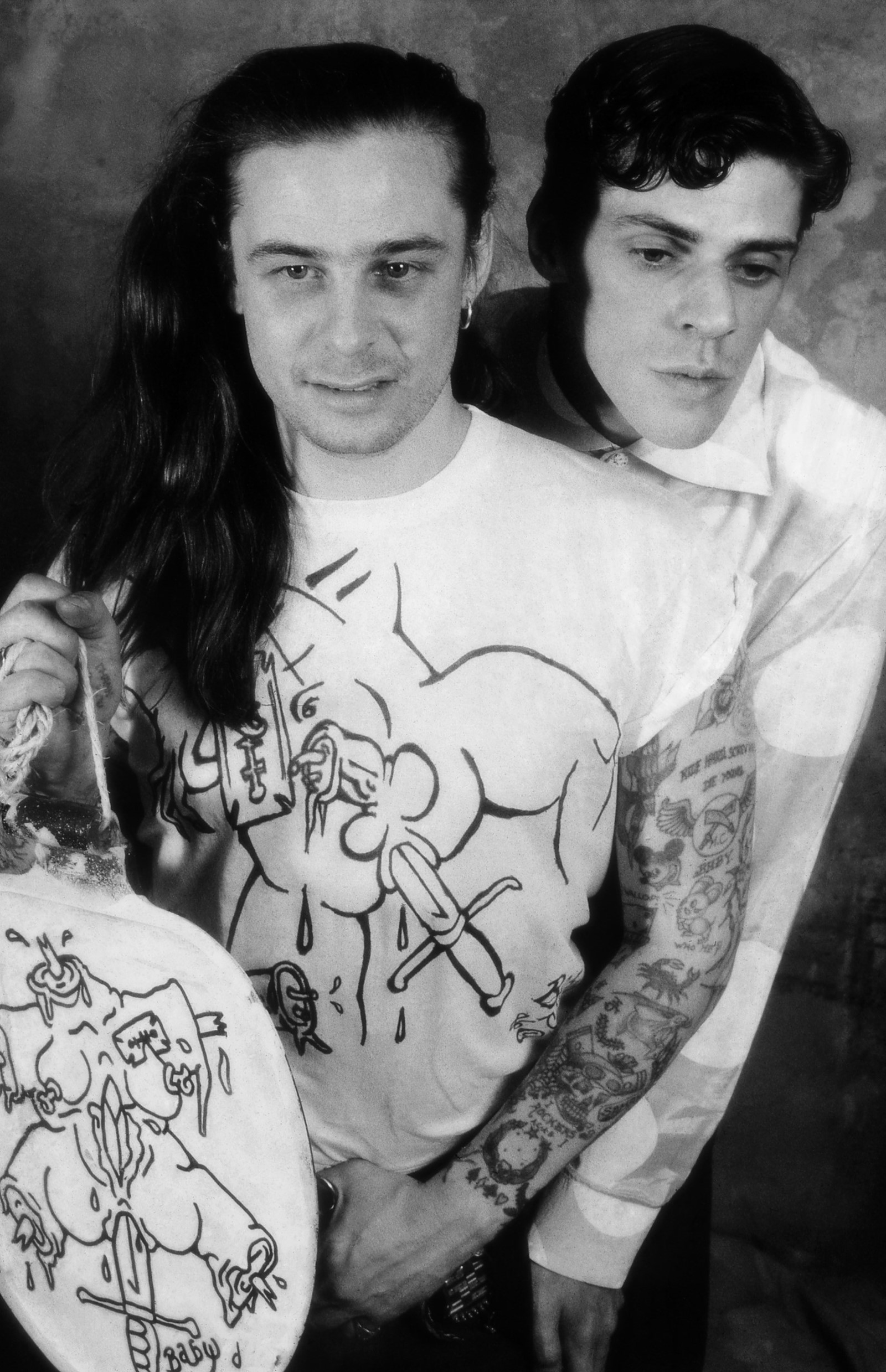

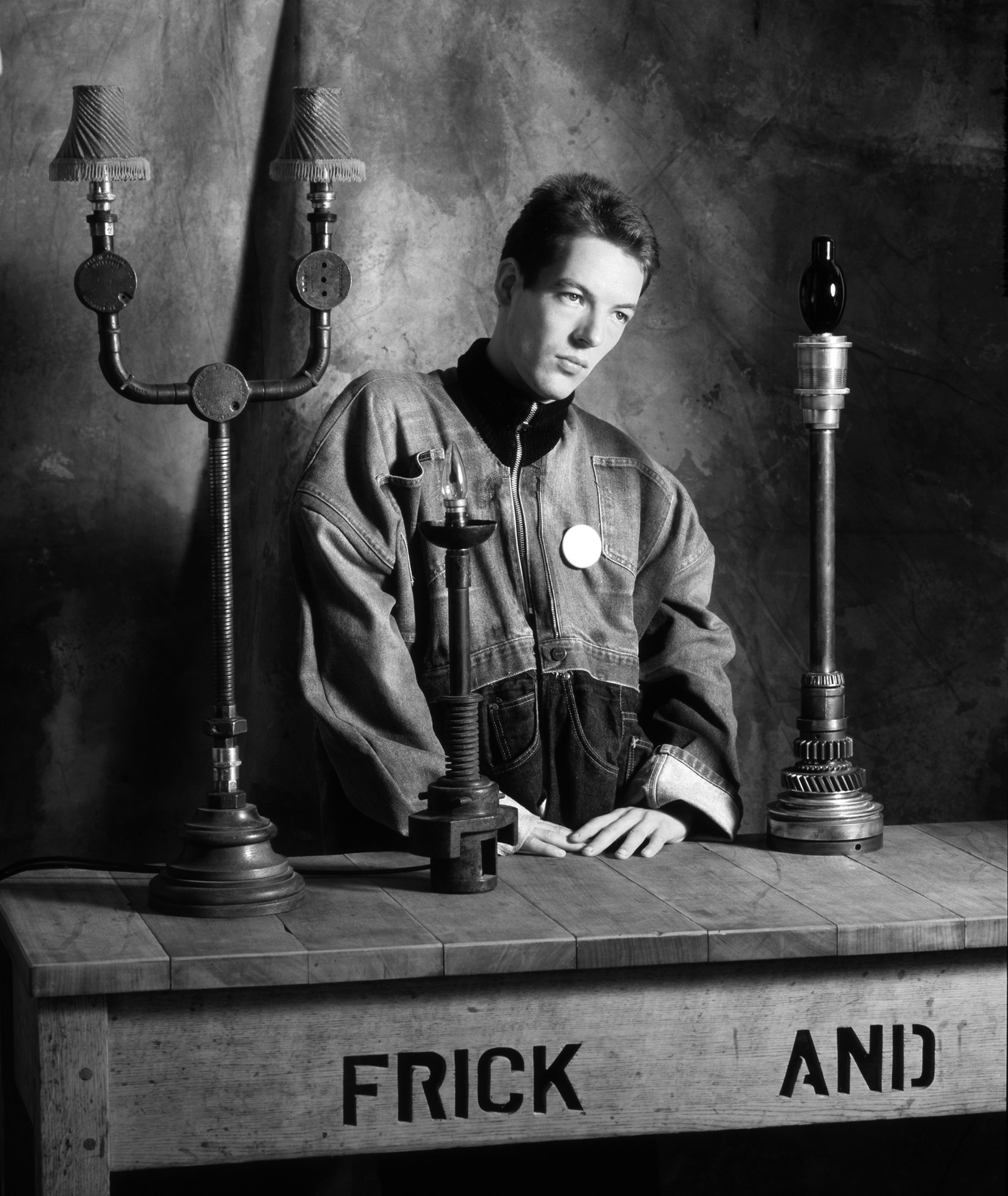

The collective was formed as a post-punk resistance to normative mass culture, favouring a salvaged, dystopian aesthetic and radical, crafty process during a Thatcherite government that prized privatisation and the fragmentation of society. Its leader was John Moore, a shoe designer, and its disciples were stylist and accessories designer Judy Blame, furniture makers Fric and Frack (Alan Macdonald and Fritz Soloman), artist and fashion designer Christopher Nemeth, knitwear designer and provocateur Dave Baby, as well as photographers Mark Lebon and Cindy Palmano. They all grew up idolising Bowie and Bolan, as well as Waters and Westwood, which informed their do-it-yourself attitude and provocative, often ironic humour.

Much like Tom Dixon's Creative Salvage, Joe Rush’s Mutoid Waste and the more commercially celebrated Ron Arad, HOBAC sought to reuse waste and found objects at a time when the discussion surrounding recycling and environmental awareness was in its infancy, considered as a fringe concern instigated by hippies. This methodology highlighted overproduction and the government’s mismanagement of resources and waste, creating a romantic alternative to modernisation, much like William Morris and John Ruskin had done before.

A Legacy of Subversion

Until recently, House of Beauty and Culture’s influence was widely felt, yet barely documented. As legend (or perhaps rumour) has it, Martin Margiela visited the shop and was so inspired that he opted to abandon couture to become a deconstructionist. Derek Jarman, Leigh Bowery, Boy George and Cerith Wyn-Evans were just some of the shop’s customers, whilst Gregor Muir, director of the ICA, goes as far to say that it foreshadowed the work of the early YBAs and provided a missing link between the likes of Tony Cragg and Richard Long, and the younger generation of artists that subsequently came to claim the Turner Prize. Kasia Maciejowska’s new book, published by the ICA in conjunction with its Judy Blame: Never Again exhibition, provides a definitive account of the short-lived creative community, many of whom are featured throughout the ICA show. Maciejowska writes about the diverse cast of characters in glorious Technicolor, lending a cinematic narrative to the otherwise research-led tome that paints an objective picture of the subversive creative and nightlife scenes that operated on the edges of society. The completion of book was no mean feat, considering that Cindy Palmano told the author that "writing about the House of Beauty and Culture is like using maths to understand a tree".

"Matthew Glamorre told my friend [curator] Leanne Wierzba about it at a party... and there wasn’t really anything on the Internet,” says Maciejowska, an art and design journalist who began researching HOBAC as her thesis at the Royal College of Art in 2011. Next to nothing was available at the time, with the exception of the surviving members and personal archives, such as the one amassed by Kim Jones, Louis Vuitton’s menswear style director. “It’s about preserving the memory rather than theorising. They were very much building their own world and it’s so much to do with their personalities.”

Maciejowska interviewed Macdonald, Blame, Baby, Torry, Palmano, Lebon, Hinton, Jones, as well as Susan Bartsch, who represented the designers in her Manhattan boutique and briefly held a showroom her Chelsea Hotel apartment, where Janis Joplin happened to live next door. The transcripts are included in the book, alongside essays that explore the work produced by these creatives and the radical design of the space itself, as well as the cultural bricolage of the East End, the post-punk approach to subcultural identification and the bacchanalian hedonism that acted as a glittering backdrop, offering utopic ecstasy in dystopian London.

A Voyage of Discovery

“It was small, tiny in fact, and filled floor-to-ceiling. Going in felt like a voyage of artisanal discovery with a sense of craft and concept creeping into every aspect,” Princess Julia tells Maciejowska in the book. Blame and Moore lived upstairs, in a shared studio space with Torry and, occasionally, Nemeth. Fric and Frack created the interior of the shop and made furniture, which would sometimes be taken to Dave Baby who would carve phalluses, demons or swastikas (reappropriated as a means of subversion) into them. “John was relaxed and generous and that allowed the other characters to bring in their own influences,” says Maciejowska, who points out that although each of the creatives’ production methods and design approaches differed, they often collaborated and shared an ideology of collage, assemblage and bricolage. Maciejowska also points out that Moore’s shoes were often inspired by historicism and craft processes, featuring unusual square toes and extended lasts that were achieved by refined workmanship, whereas Blame, Fric and Frack and Nemeth lent a rougher edge to the space, imbuing street-based influences and waste materials with a more dishevelled and urban look.

The shop itself was a melting pot of these influences and aesthetics, much like the works on display. In 1987, the New York Times described how HOBAC’s floor was studded with coins and there was change scattered on the floor, which Blame recalled was crunchy to walk on, and which indicated an ironic commentary on having no money yet stepping on it nonetheless. The Fric and Frack furniture was in constant circulation, either being borrowed or bought, and Dave Baby had cut demon-shaped holes into the wall, while Trojan and John Maybury had painted a dual sign for the shop frontage. “People were allowed to just come in and do what they wanted,” explains Maciejowska. “It was sort of an act of refusal to conform and probably a side effect of their hedonism that the shop was hardly ever open – you had to knock and knock and hope someone would answer.”

Burroughs' Boys

When considering the spirit of HOBAC, Alan Macdonald cites the passage in The Wild Boys, William Burroughs’ 1971 novel, that depicts garments covered in vomit which, upon closer inspection, are actually beautifully embroidered. Burroughs’ novel became a key reference for the collective, who related to its feral pack of homosexual, drug-taking boys who embark on battles in the name of liberty. It inspired the dishevelled, urban and predominantly masculine aesthetic that moved away from the New Romantics and paved the way for an altogether more urban sensibility that would inform the acid house revellers of the rave scene. “It all came from this little niche moment at Taboo,” says Maciejowska, who adds that it was the first club in London to have access to ecstasy, which informed the euphoric sensibility of the atmosphere that would go on to change British club culture.

It is clear that the group’s hedonism was an escapism from the dire sociopolitical and economic backdrop, offering a space for likeminded creativity and sexuality at a time when being gay meant being subject to social persecution whilst dealing with the devastating AIDS crisis. House of Beauty and Culture closed in 1989 after John Moore died from a cocaine overdose and each of the members grew into individual creative careers of their own. Together, they were part of an East End subculture that was rooted in artistic practice, post-punk rebellion and the resistance of mainstream mass culture and overproduction. “It was modern age compared to the rest of history, but then five years later the Internet changed everything,” says Maciejowska. “It really was the last underground subculture.”

Kasia Maciejowska will be signing copies of 'The House of Beauty and Culture' at Dover Street Market London on July 4, from 5-7pm.