James Balmont rounds up five films from the 1960s – one of the most radically artistic periods in Japan’s filmmaking history

Having already showcased the Y2K J-Horror revolution, the BFI now looks to the Japanese movies that transformed the filmmaking landscape in the 1960s this December, in the latest chapter of their extensive Japan 2021 season. It is a period, without a doubt, that remains one of the most radically artistic in the country’s filmmaking history.

Born against a backdrop of social unrest as the country endured some of the biggest student protest movements on record, the Japanese New Wave also coincided with a period of significant societal change. Rapid economic growth ensured that the average person’s income would double by the end of the decade. Major film studios, on the other hand, faced bankruptcy as the advent of television transformed the mode of entertainment consumption. Cinema attendance halved between 1958 and 1963, with the low-key popularity of erotic “pink films” screening at independent adult theatres also damaging mainstream box office profits.

Radical change was necessary to keep the film industry alive. And so, as the French New Wave shook thing up in the west, so too did scores of young and hungry Japanese filmmakers, as avant-garde arts scenes thrived in the metropolis of Tokyo. Emerging from the shadows of some of the country’s leading filmmakers were hungry new directors like Nagisa Ōshima, Seijun Suzuki and Shōhei Imamura, who were commissioned to make their own films having previously only worked as assistants.

While there was no distinction of vision or style shared among the New Wave directors, they were unified by their commitment to exciting new brands of filmmaking that often dealt with taboo subject matter, violence, sexuality, race relations, and alienation. They experimented radically with style and form through their editing, camerawork and narrative conventions, often blurring realism with fantasy for the purpose of cutting social commentary or just pure entertainment. The end result was a wealth of some of the most vibrant movies the country had ever seen, as the decade proved a turning point for Japanese culture, politics and society.

To celebrate the BFI’s Japanese New Wave programming, AnOther has highlighted five key films screening in theatres in the UK this month, with many also available via the BFI Player and via the Criterion Collection in the US.

Woman of the Dunes, 1964

Shot in resplendent monochrome, Woman of the Dunes possesses all the hallmarks of a great horror film without ever truly veering into the trappings of the genre. Dissonant strings screech as shaky-cam close-ups capture wriggling, alien-like insects over the delirious desert-scape of Japan’s Tottori Sand Dunes. Squint a bit, and these wastelands could be the planet Arrakis of Dune, or Star Wars’ Tatooine – though the images and atmosphere within better resemble that of David Lynch’s surreal debut Eraserhead.

The plot is simple: a fanatic entomologist, who snaps obscure mini-beasts on vacation, takes shelter for a night with a strange woman living at the foot of a sandy sinkhole. When he tries to leave in the morning, he finds oppressive forces of nature preventing his departure, and as sandstorms rage and the house itself shakes, silhouettes and shadows entrap him. Desperate hallucinations project surreal visions of sandy patterns and otherworldly environments (the masterful work of cinematographer Hiroshi Segawa), as the doomed protagonist falls into an intense sexual relationship with his new landlady, whose husband and daughter, she says, were lost to the desert some years ago.

Adapted from Kōbō Abe’s widely successful 1962 novel, Woman of the Dunes picked up the Cannes Film Festival Special Jury Prize upon its release in 1964, before being nominated for two Oscars the following year. Teshigahara ultimately lost the Best Director prize to Robert Wise for The Sound of Music.

Pale Flower, 1964

“Tokyo … It makes my head spin,” comments the narrator of Pale Flower, in a disorientating opening montage that combines rushing crowds, industrial plants, and busy train platforms with the sounds of screeching whistles and car horns. Ostensibly, Muraki – a yakuza just released from prison, who keeps a severed pinkie in his pocket – is talking about how the city has changed since he was imprisoned for murder. But equally, this introduction alludes to the hustle and bustle of the film’s primary focus: the illicit gambling dens of the country’s capital.

Set to a cacophonous score of avant-garde jazz, this noir is the tale of the aforementioned and his tentative romance with a woman named Saeko, who is so addicted to gambling that she even plays in bed. Their mutual destruction is captured in brilliant monochrome, with the film’s creative peak eventually arriving in the form of a surreal dream sequence that combines slow-motion, superimposed images and the sounds of manic laughter.

The film was initially shelved for months by Shochiku studio upon its completion, with its nihilistic tone deemed unsuitable for public consumption (screenwriter Masaru Baba, meanwhile, was unsatisfied with the film’s emphasis on visual and audio style). When it was eventually released, it was slapped with an adults-only rating, which actually helped it to become something of a hit. With director Shinoda a central figure within the wider Japanese New Wave, the film is now set for a UK Criterion Blu-ray release in 2022, following a pair of BFI Southbank screenings in December.

Tokyo Drifter, 1966

You could be easily fooled into thinking that you were watching the trippiest James Bond film ever made with Seijun Suzuki’s Tokyo Drifter (also available via Criterion in the UK). Across a lean 90 minutes, this yakuza thriller covers car crushings, booby traps, free-jazz nightclubs and eyepatch-wearing gunmen, bound together by shootouts that wouldn’t feel out of place in a spaghetti western. But beyond the prototypical gangster plotting, the film is elevated to a realm of visual lucidity thanks to brilliant technicolour visuals and delirious set design, in this classic work from Seijun Suzuki – an icon of the Japanese New Wave. Put simply, this is a film that demands attention; not because it’s complicated or profound and nuanced, but because it is uncompromisingly stylish, and visually dazzling.

Suzuki’s prolific work rate (he’d directed nearly 40 movies by the time Tokyo Drifter was released) would find parallels in the similarly stimulated work of Y2K provocateur Takashi Miike (Audition) decades later. His eye-boggling visual style, meanwhile, has been cited as an influence on everyone from Quentin Tarantino to Jim Jarmusch. The latter director even thanked Suzuki in the credits of the 1999 mobster film Ghost Dog: Way of the Samurai, starring Forest Whitaker, and the film itself pays homage to the 60s director across numerous referential shots.

Death by Hanging (Nagisa Ōshima, 1968)

Death By Hanging’s opening exposition reveals that 71 per cent of voters in a 1967 poll were opposed to the abolishment of the death penalty, before breaking the fourth wall to ask “Have you ever witnessed an execution?” What follows is a step-by-step examination of the horrifying process, climaxing with the repeated shot of a man being plunged through a trap door with a noose wrapped around his neck.

But the man sentenced to die, a Korean rapist and murderer, inexplicably survives having lost all memory of his crimes. The remainder of the film then becomes a bleak and satirical exploration of racism, colonialism and morality as the perplexed guards of a Japanese prison re-enact his crimes in an attempt to evoke a recognition of guilt, so that they can kill him all over again with a clear conscience. The film blurs moral boundaries between captive and captor, as the various ethical dilemmas of the situation are laid bare.

Director Nagisa Ōshima would find international fame and notoriety in the decades that followed. Sexually-explicit 1976 feature In The Realm of the Senses landed the director a court case in Japan, while 1983 war film Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence cast none other than David Bowie as the lead. His final film, 1999 queer samurai drama Gohatto, would also feature some of the era’s most compelling screen presences, including superstars Tadanobu Asano and actor-director Takeshi Kitano.

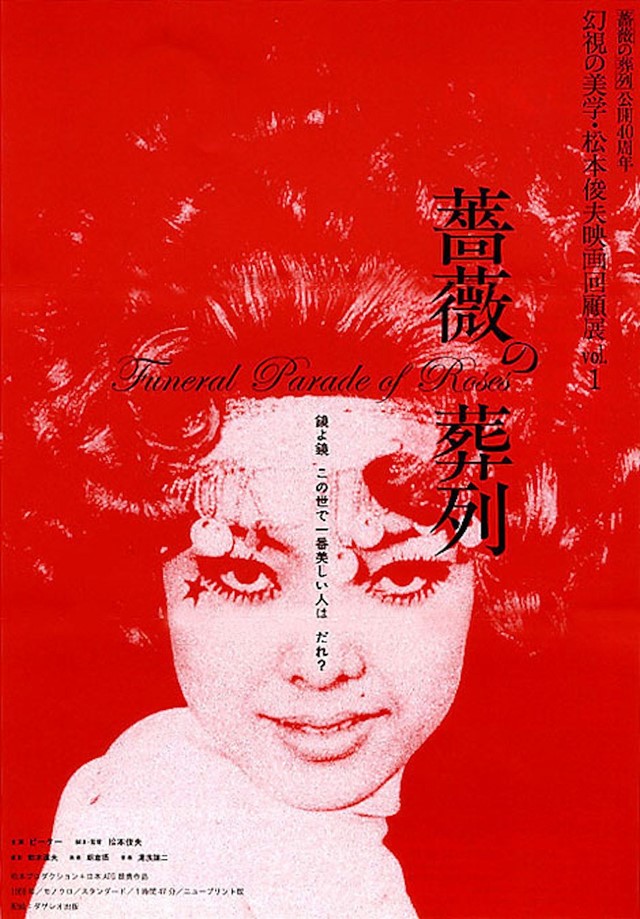

Funeral Parade of Roses, 1969

As sexual liberation became increasingly visible in the west during the swinging 60s, so too did attitudes towards sex change in Japan. By the end of the decade, both avant-garde arts and a thriving gay scene became prominent in downtown Shinjuku, in the sprawling capital of Tokyo.

In the opening of this audacious work, the saturated white skin of a naked male torso is captured in extreme close-up. “I am the wound and the blade, both the torturer and he who is flayed,” reads the on-screen text, as a topless male fornicates with a stunning transvestite man. This is Funeral Parade of Roses: the most Warhol-esque of the New Wave films on this list, and perhaps the greatest queer film ever to emerge from Japan.

Filmed in a Godard-ian style that fuses chaotic jump cuts with handheld camerawork, Funeral Parade of Roses is the story of Eddie (played by the androgynous icon Peter) – a Shinjuku “gay boy” who revels with his fellow “queens” in the city’s hedonistic gay quarter. It’s a dizzying and experimental journey that combines orgasms and marijuana smoke with psych-rock dance-offs, jumping from snapshots of naked bums spouting blooming flowers to stabbings and Buñuel-esque eye gouges.

With a cast largely built of real amateurs from the gay scene, it also deliberately melds narrative fiction with jarring documentary realism – as transvestites rocking Yayoi Kusama-style wigs break the fourth wall to answer questions like “How long have you been gay?” and “How long have you been a queen?” Today, the film is considered an avant-garde classic, with parallels observed in everything from noted fan Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, to Hirokazu Kore-eda’s After Life, and Jennie Livingston’s Paris Is Burning. It returns to the BFI Player this month alongside cinema screenings in Southbank.

The BFI’s Japan 2021 season will run until the end of December. For more information, and for tickets, visit the official website.