With a near-permanent expression of “no fucks given” plastered across his face, indie film mega-star Tadanobu Asano personifies the Japanese cinema renaissance better than any other actor

Raised on The Sex Pistols’ punk music and historically dividing his time between performing in rock bands, writing poetry and starring in every Japanese cult movie under the sun, the man they once called Japan’s Johnny Depp has few peers at home. Easily matching his American counterpart for off-kilter roles, Tadanobu Asano has popped up in underground hits by pretty much every big Japanese filmmaker of the past quarter-century. Behold:

Heartthrob husband in a meditative exploration of grief? See Maborosi, by Cannes Palme d’Or winner Hirokazu Kore-eda. A remorseless murderer with a penchant for jellyfish? Check out Bright Future, by 2020 Venice Silver Lion winner Kiyoshi Kurosawa. Sword-wielding avenger in an ancient Japanese folk tale? That’s Shinya Tsukamoto’s Gemini, which finally receives a UK release this November after a 20-odd year wait. The list goes on – because, in the past 25 years of Japanese cinema, there have been few actors as iconic as Asano, the go-to cool guy in every directors’ phone book.

With his small-screen presence bold enough to grant him a leg-up into Hollywood the 2010s, Asano can nowadays be found in all manner of Western hits. From a spirit-breaking interpreter in Martin Scorcese’s historical epic Silence, to Thor's ball-and-chain-wielding warrior buddy Hogun in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Asano’s steely detachment remains a constant allure. And since he’s now battled Keanu Reeves in 47 Ronin, mentored Jared Leto in yakuza crime flick The Outsider, and led an army as Genghis Khan in the Oscar-nominated epic Mongol, it’s safe to say that Asano’s stature remains solid.

But before he made the jump, Asano was the king of the indies in Japan – and in a few other East Asian territories, for that matter. So here are five unforgettable turns to illustrate why, in a year starved of new cinematic splendours, a look at an Eastern small-screen sensation is long overdue.

Electric Dragon 80.000V, 2001

Directed by 80s arthouse pioneer Sogo Ishii (Crazy Thunder Road, Burst City), this 55-minute cyberpunk explosion pits Asano’s Dragon-Eye Morrison against the villainous Thunderbolt Buddha, in a comic book-style battle that threatens to destroy the whole of Tokyo. With each combatant wielding surging electricity as their weapon, the question is simple in this black-and-white caper: which shocker will emerge victorious?

Dragon-Eye Morrison is Asano’s amped-up hero in this super-stylised passion project, seen as director Ishii’s long-overdue return to the intense cyberpunk films he had pioneered in the 80s. Guerilla scenes of him riffing on a guitar in the middle of a busy pedestrian intersection were filmed without the public’s knowledge, and the hyper-kinetic editing is a feast for the eyes from start to finish. The searing, industrial soundtrack, meanwhile, was penned by Asano and Ishii’s explosive avant-garde punk band: MACH-1.67.

Critically acclaimed upon release, Electric Dragon 80.000V actually bankrupted the production company behind it after it failed at the box office alongside Ishii and Asano’s other film that year: Gojoe. To be fair, you don’t get much more punk than that.

Ichi the Killer, 2001

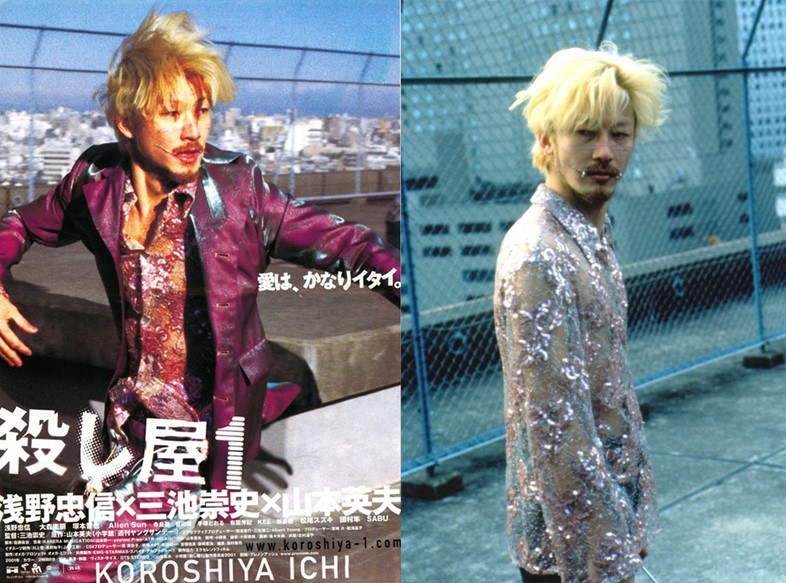

Tadanobu Asano’s most memorable acting performance remains not only a career highlight but also one of the most iconic film roles in modern Japanese cinema. Adapted from a violent manga series by cult filmmaker Takashi Miike (Audition, Thirteen Assassins), Ichi the Killer follows Asano’s facially-mutilated yakuza enforcer Kakihara as he attempts to reap revenge on the man who murdered his gangland boss – hoping to meet a match for his own depraved brutality in the process.

Numerous scenes from Ichi the Killer remain censored in the UK due to their gratuitous violence, and much of the controversy is directly attributed to Asano’s sadistic lead. Kakihara’s methods of torture include fish hooks, tempura oil, and razor-sharp skewers; but it is his larger-than-life presence (and outrageous appearance) that makes him such an enduring cult character.

With a wardrobe that combines sequinned shirts, tartan slacks, mauve trenchcoats and velvet suits, this peroxide blonde, chelsea-smiling mobster is a constantly electrifying presence in a film pulsating with style and menace. A villain for Japan’s all-time-greatest rogue’s gallery – it is a role Asano was born to play.

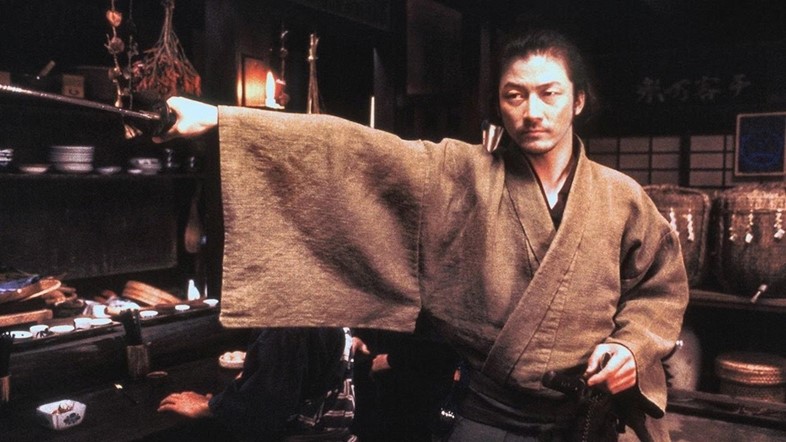

Zatoichi, 2003

Zatoichi, the blind swordsman, is to Japanese cinema what James Bond is to Britain: a home-grown film icon whose antics span a wildly uneven range of theatrical releases.

By the time crime auteur Takeshi Kitano made his move to write, direct and star in this turn-of-the-century franchise revival, the character had already been the focus of 26 feature films, four TV series’ and an American remake starring Rutger Hauer. But Kitano’s epic, Kill Bill-style samurai-action-musical hybrid would be the toast of them all. It won the Silver Lion for Best Director at Venice 2003, grossing a massive $24 million at the Japanese box office.

The director made no bones about his intentions for Zatoichi – after a series of commercially unsuccessful works, Kitano wanted nothing more than to make a blockbuster. And part of this process was to cast fast-rising actor Asano in a pivotal role: masterless samurai Hattori, the blind swordman’s nemesis in a town of feuding gangs in Edo-era Japan.

Asano’s detached aura would be a perfect fit for the jaded bodyguard-for-hire. And for his stoic performance, Asano received a nomination for Best Supporting Actor at the 2004 Japanese Academy Awards.

The Taste of Tea, 2004

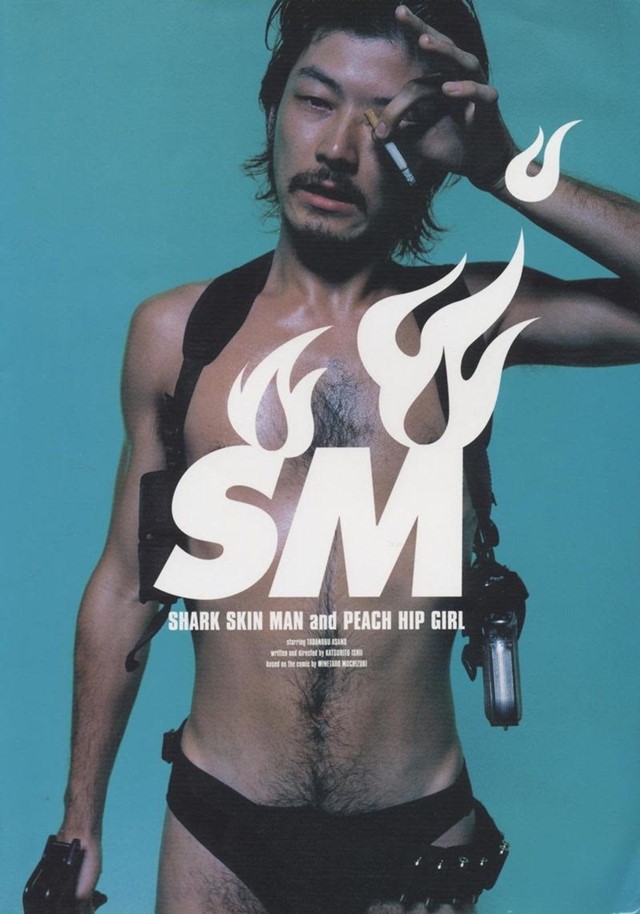

This absurd comedy is rightfully considered Japanese filmmaker Katsuhito Ishii’s answer to Wes Anderson’s The Royal Tenenbaums. Starring Asano (who previously starred the director’s Tarantino-inspired Shark Skin Man and Peach Hip Girl in 1999) alongside a host of captivating character actors as members of the eccentric Haruno family, The Taste of Tea finally received a UK Blu-ray release courtesy of Third Window Films this October – and it’s worth the wait.

As six-year-old daydreamer Sachiko strives to escape her giant imaginary doppelganger, senile grandpa Akira breaks into song and dance at the drop of a hat. But despite their quirky personalities, Asano’s lazy music producer uncle Ayano easily gives them a run for their money for most memorable character in this vibrant countryside fantasy-drama.

Introduced by way of an extended vignette, in which he details the story of the first time he ever took a shit in the woods, Ayano soon finds himself involved in a number of eventful encounters across the film’s meandering narrative. Be it an awkward rendezvous with an old flame in front of a convenience store, or a bizarre recording session with a pretentious animator, Asano’s languid performance elevates Ayano into an offbeat slacker who is funny right to the end.

Ruined Heart: Another Love Story Between a Criminal & a Whore, 2014

In 2017, Asano took home the Best Actor Award at the Asian Film Awards for Kōji Fukada’s Harmonium, a Cannes Jury Prize-winner the year of its release. His role as a murderer released from prison, who oversteps boundaries as he attempts to reintegrate into society, fit the coolly detached performer as much as anything he’d done prior. But just a few years earlier, Asano’s role in a lesser-known indie flick from the Philippines harked back to the days before he’d hit the big time. Ruined Heart was a return to Asano’s roots – even if it wasn’t filmed in his home country.

A kinetic, vibrantly colourful and largely dialogue-free crime romp set in the back alleys of Manila, Ruined Heart is built upon its riveting sense of style. It follows Asano’s nameless, broken-armed criminal on a series of wild exploits with his prostitute lover – and though the story is paper-thin, this tour-de-force of filmmaking verve should, by rights, put Filipino arthouse cinema on the map.

Shot in documentary style by legendary cinematographer Christopher Doyle (In The Mood For Love, 2046), and featuring a wild soundtrack that comprises surf, blues and krautrock, Ruined Heart almost feels like a 70-minute music video. It’s stock full of gratuitous long-takes and dizzying foot-chases, but for all its creative ambition, it is Asano who is the film’s magnetic heart that keeps everything beating.

Whether he’s manically playing the drums in a midnight street party or sloshed out in the basement of a seedy underground bar – this chain-smoking, pistol-wielding tearaway is Asano distilled to the core. Ruined Heart, ultimately, is a latter-day reminder of why Asano’s unique, effortless cool continues to transcend borders and boundaries to this day.