Do we live on in photographs; can they offer us a kind of immortality? Or do we figuratively die the moment our photograph is taken, after which the image painfully recapitulates death itself? Perhaps the photographed subject occupies a space between the two, not quite alive, not quite dead.

These are just some of the questions that arise in the work of New York photographer Peter Hujar, whose series Portraits in Life and Death is currently showing in Europe for the first time. Walk through the rooms of the exhibition at the 60th Venice Biennale and you’ll run into some familiar faces; John Waters, Susan Sontag, Fran Lebowitz and William Burroughs are among those Hujar photographed in his studio, all of whom were his friends. But the show offers more than a hall of fame. Alongside the portraits of celebrities are those of lesser-known figures from Hujar’s 1970s Lower East Side artistic milieu, captured in intimate states of repose and vulnerability, as well as a haunting set of images taken a decade earlier, in the early 60s, of embalmed bodies in the Capuchin Catacombs in Palermo, Italy.

That these photos of eerie and entombed remains sit alongside the black and white portraits of contemporaries was Hujar’s intention; he placed the two series side by side in his first and only monograph, also titled Portraits in Life and Death, published in 1976. Hujar’s friend, the writer and critic Susan Sontag wrote in the book’s introduction, “Photography ... converts the whole world into a cemetery. Photographers, connoisseurs of beauty, are also – wittingly or unwittingly – the recording angels of death. We no longer study the art of dying ... but all eyes, at rest, contain that knowledge. The body knows. And the camera shows, inexorably.”

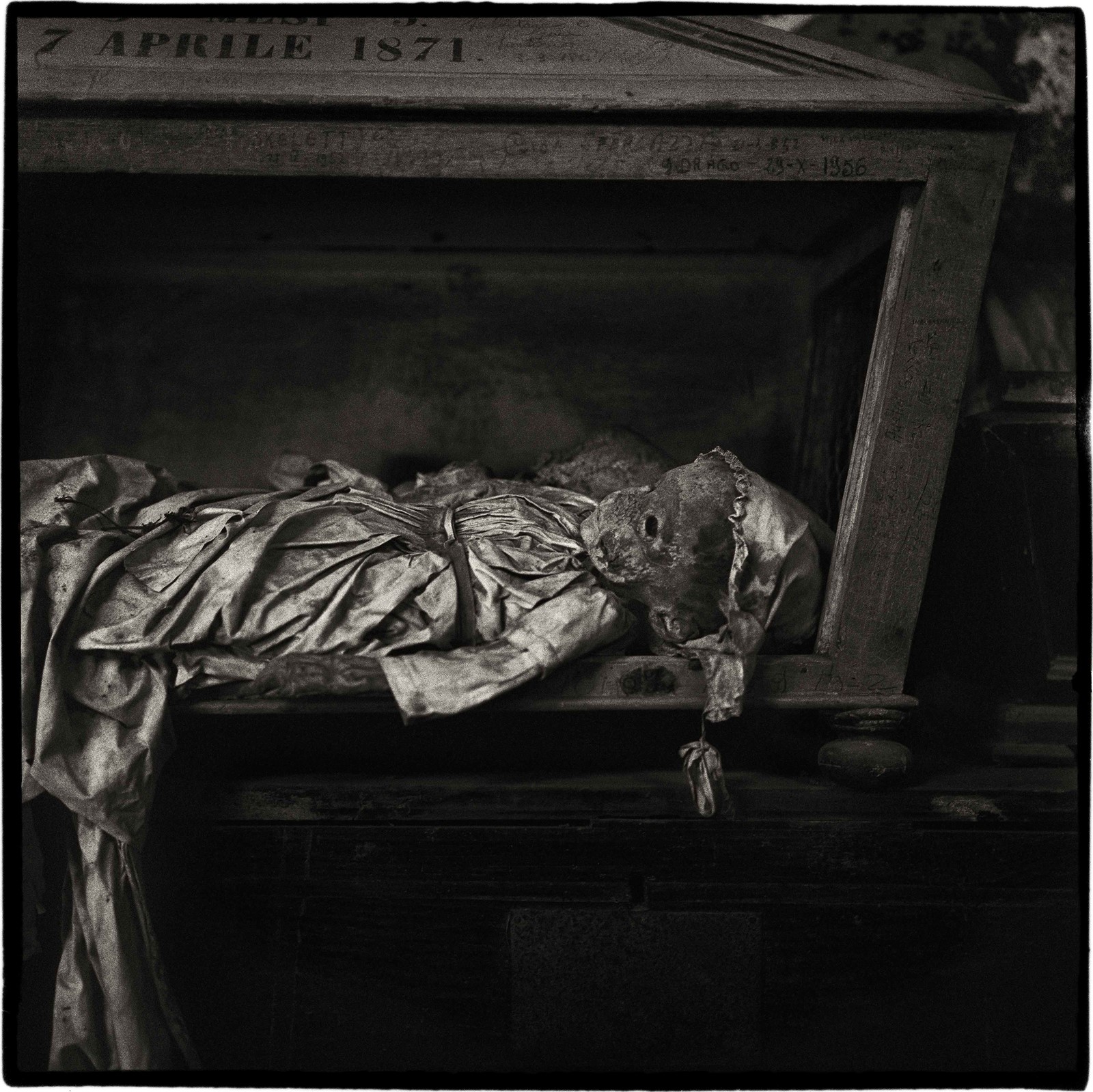

We often think of death as the great equaliser. We all die eventually. One of the most striking images in Hujar’s collection – a masked corpse that appears to be laughing, and the cover image for the monograph – seems to make this point. Yet the reality presents a more complicated picture. Death may be accelerated for those without the means to stave it off through access to the right healthcare, as the untimely death of many of Hujar’s subjects illustrates. There is also the question of who is granted the privilege of remembrance. Take the catacombs where Hujar photographed the mummified bodies, which attest to this uncomfortable fact: the people preserved there were well-known or elite figures who could afford to pay for the embalming process and to be kept on view.

“The catacombs were created for the elite to remain as lifelike as possible, a space for visitation and remembrance,” explains the Venice show’s curator, Grace Deveney. “In those photos, Hujar is drawn to bodies in frames and set up for display. The catacombs were an early way of thinking about photography’s unique possibility to bring life and death together and fix them through these momentary glimpses. When he turns to portraiture he is capturing people with a sense of impending death in life.”

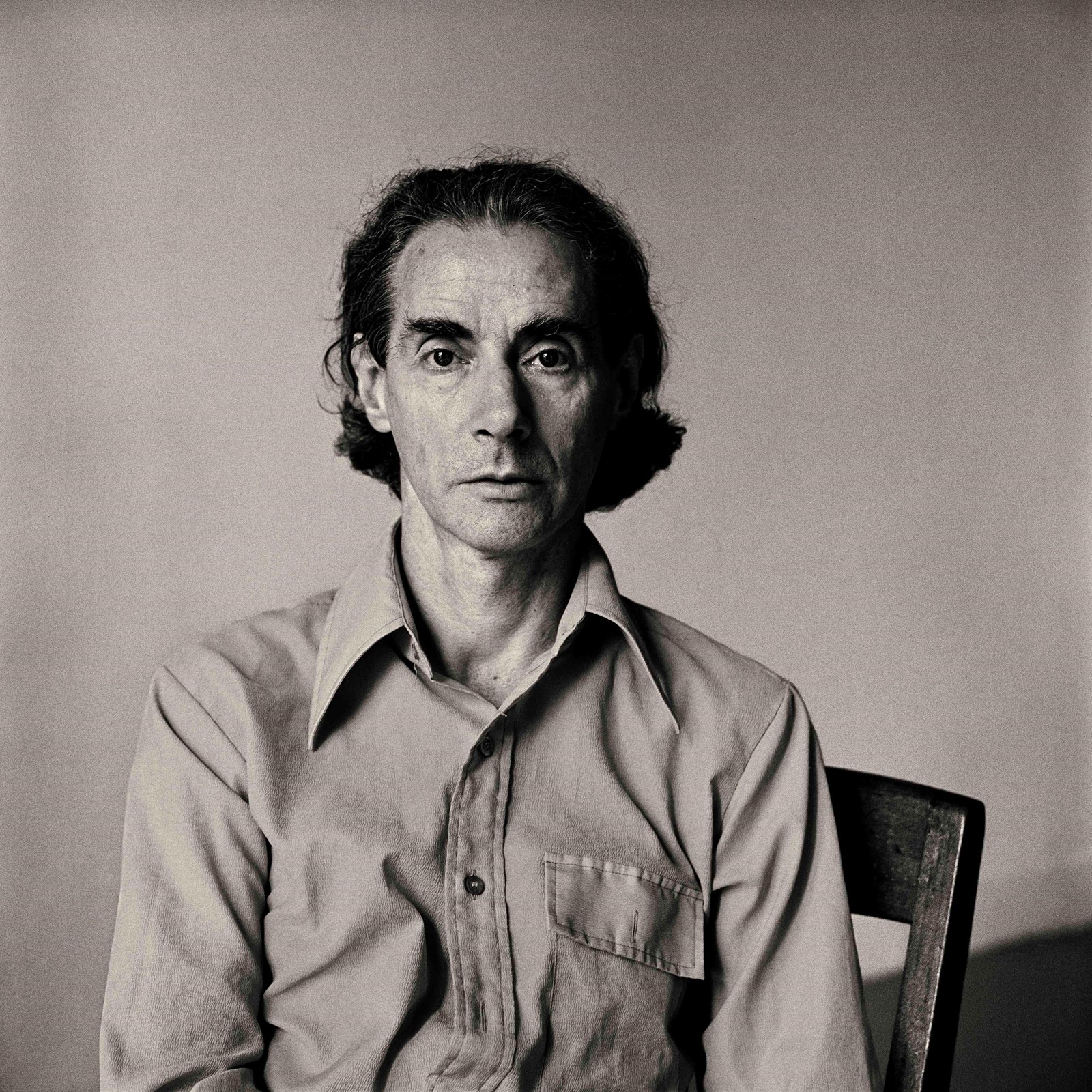

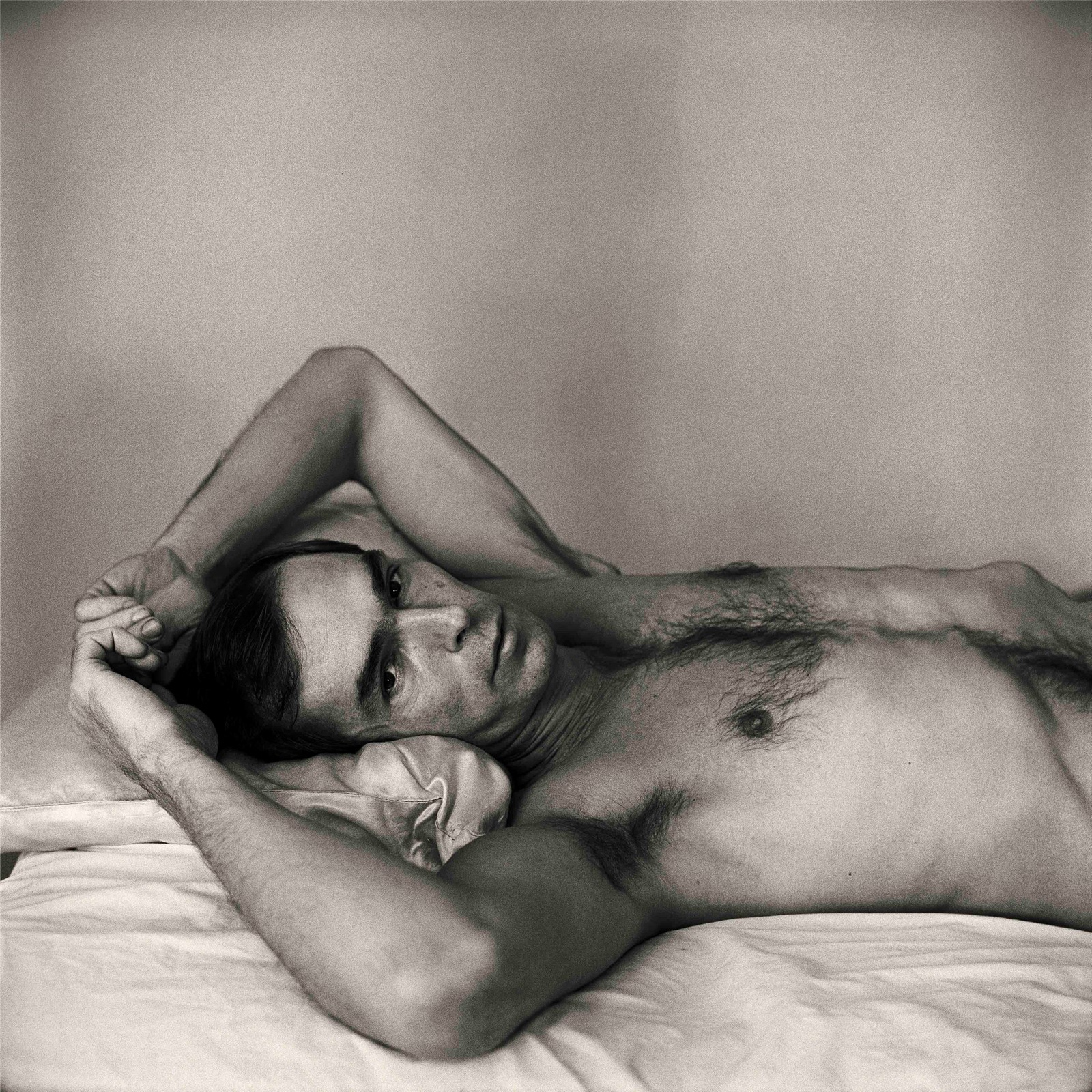

Like the catacomb photos, with their coffins and encasements, in his studio portraits, Hujar’s frame appears to encapsulate and hold his subjects, often as tenderly as they had just died in his arms. Some later did; one image in the show features James Waring, a dancer who died in his fifities, with Hujar taking care of him. Other images Hujar later took (not present in the Venice show) include an image of Warhol superstars Jackie Curtis – after death from a heroin overdose – and Candy Darling, on her deathbed before she passed away from lymphoma at just 29 (an image that later became an album cover for Anohni and The Johnsons).

When Hujar himself was hospitalised in 1987 from Aids-related illness, the artist David Wojnarowicz, Hujar’s former lover, turned the photographer’s camera around, capturing Hujar for posterity, as though not only to complete the Portraits In Life and Death series, but to document the grave tragedy and injustice of the ongoing Aids crisis. Look hard enough at Hujar’s portraits, and you might discern a knowing look in his subjects that seems to foreshadow how Aids would ravage the landscape of the East Village, taking the lives of this network of mostly queer performers and artists that Hujar surrounded himself with.

Although many of Hujar’s subjects are people of note, Deveney suggests “he was not drawn to photographing famous people” but – as Hujar himself put it – “those who push themselves to any extreme [...] and people who cling to the freedom to be themselves.” Dancers and people with dynamic practices were a draw, says Deveney, referencing portraits of Kenneth King, a dancer and choreographer, and Larry Reed of the Trocadero dance troupe. “I think he photographed them in these moments of rest, not moments of performance, because he was interested less in performers on stage or as public facing artists but as people who, outside of the image, can do this extraordinary, transformational or transgressive thing.”

Speaking to AnOther, photography critic Vince Aletti (and a friend of Hujar’s), agreed that Hujar was not preoccupied with fame. Besides the fact that many of his subjects were not yet famous at the time their portrait was taken, Aletti remembers Hujar himself as an aloof person, wary of mainstream success, and interested in cultivating authentic relationships – both with those in his personal life and with his sitters, who were often one and the same. “Peter rarely photographed people that he didn’t care about. [He] waited for them to let go, rather than giving him their ‘camera face’,” recalls Aletti.

The irony is, however, that the more famous portraits have in part, contributed to Hujar’s recent recognition in the art world and among those with an interest in queer archives and histories. Ten years ago Hujar may not have been recognisable, despite his distinct good looks (best captured in his own mesmerising self-portrait). Now, with the Venice show, and a reissue of the book Portraits In Life and Death forthcoming in October 2024, things are changing. Soon, the actor (and two-time Another Man cover star) Ben Whishaw will play Hujar in a film biopic. Little known beyond his immediate circles and barely earning a dime during his lifetime, today – long after his death – Hujar is becoming a photography superstar revered for his formal expertise and distinct ability to see into a subject’s soul.

This brings us back to the question of who is and isn’t remembered, and Hujar’s fascination with how photography can play an intervening role. As Roland Barthes put it: “In an initial period, photography, in order to surprise, photographs the notable; but soon, by a familiar reversal, it decrees notable whatever it photographs.”

Portraits in Life And Death by Peter Hujar is on show at Istituto Santa Maria della Pietà in Venice until 24 November 2024.