In November 1972, Candy Darling arrived in Hollywood for the premiere of Women in Revolt, Andy Warhol’s improvised take on the burgeoning feminist movement. He had asked her to star: “You better be nice to Paul [Morrissey] and not complain and not wear too much lipstick because you’re supposed to be a rich girl and, uh, rich girls don’t do that anymore.” Candy replied: “I know what rich girls do, Andy.”

At midnight Candy walked into Schwab’s, the fabled Hollywood hangout, wearing a six-foot-long white fox fur and, with her blonde bombshell looks, received a standing ovation. People who didn’t know who she was still asked for autographs. A performer and model, she was, to quote one writer, the “subculture Lana Turner.” When she’d cross the street back in New York, she’d stop traffic.

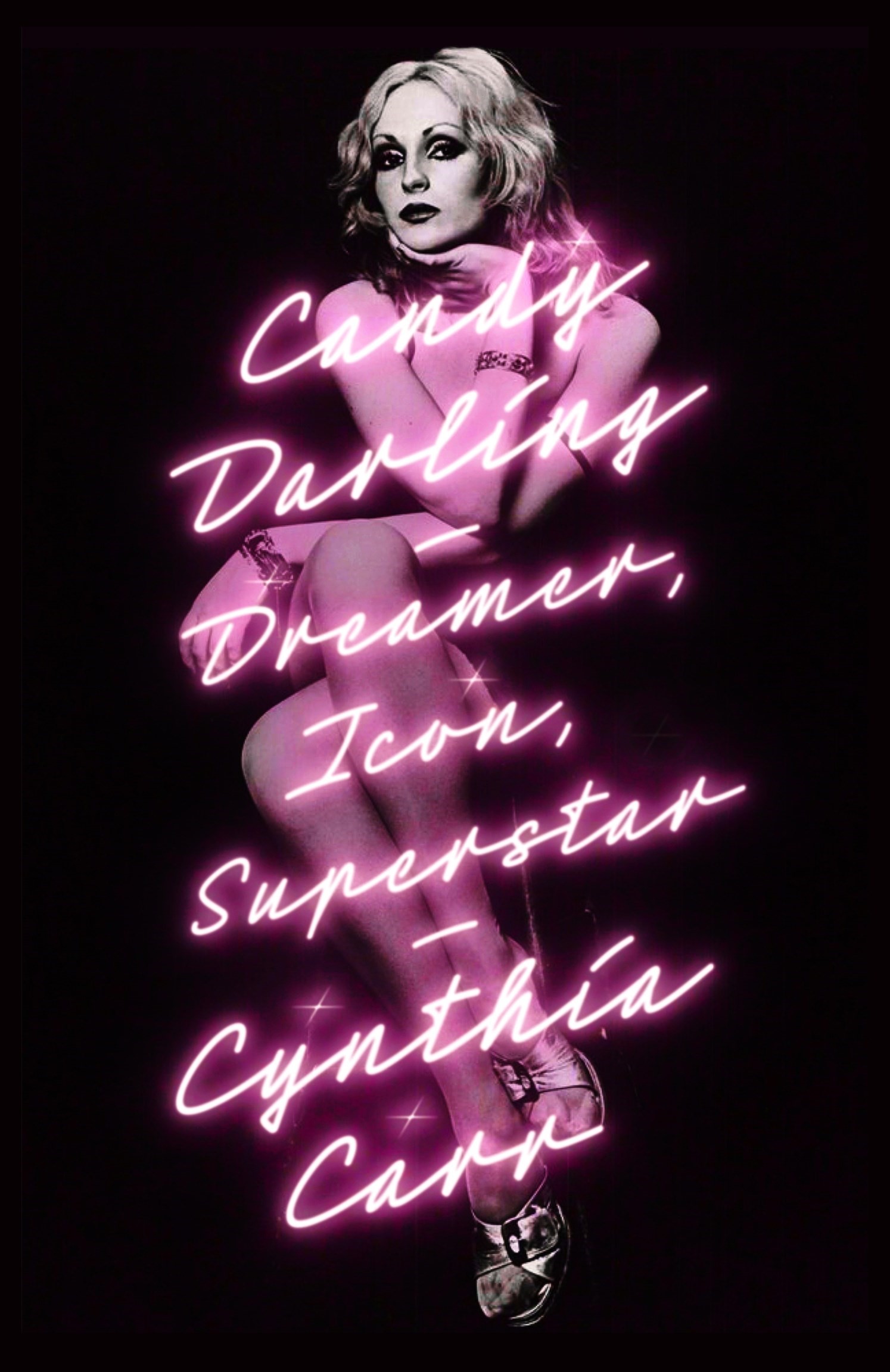

“Candy wanted to be remembered,” says Cynthia Carr, author of the new biography Candy Darling: Dreamer, Icon, Superstar about the trans pioneer. Dedicating the book to the trans community, Carr writes: “As I worked on this biography I saw that community increasingly demonised in ways both cruel and traumatising. May this account of one life make a difference. May you be understood. May you be appreciated. May you be loved.”

Below, the author sits down with Tony Wilkes to discuss Candy’s life, why she belongs to the feminist movement, and releasing the dead from silence.

Tony Wilkes: Your last book was an award-winning biography of the artist David Wojnarowicz. What made you choose to write about Candy Darling?

Cynthia Carr: What got to me was the stories of the troubles and trauma she faced, the struggle to be a trans person at that time. There was a real contrast between her everyday life and this image, this persona on top of the world. In Manhattan, she was acclaimed. She was glamorous. Warhol was taking her to fancy parties. She got to know socialites and movie stars. She was photographed by so many famous photographers. And then she’d go home and her mother was telling her: ‘Don’t come home until it’s dark. Don’t answer the door. Don’t let anyone see you.’ She had all this prejudice to face that was a big part of her life every day. That was a story I wanted to tell.

TW: I read that it took you ten years to write the book. What was that process like?

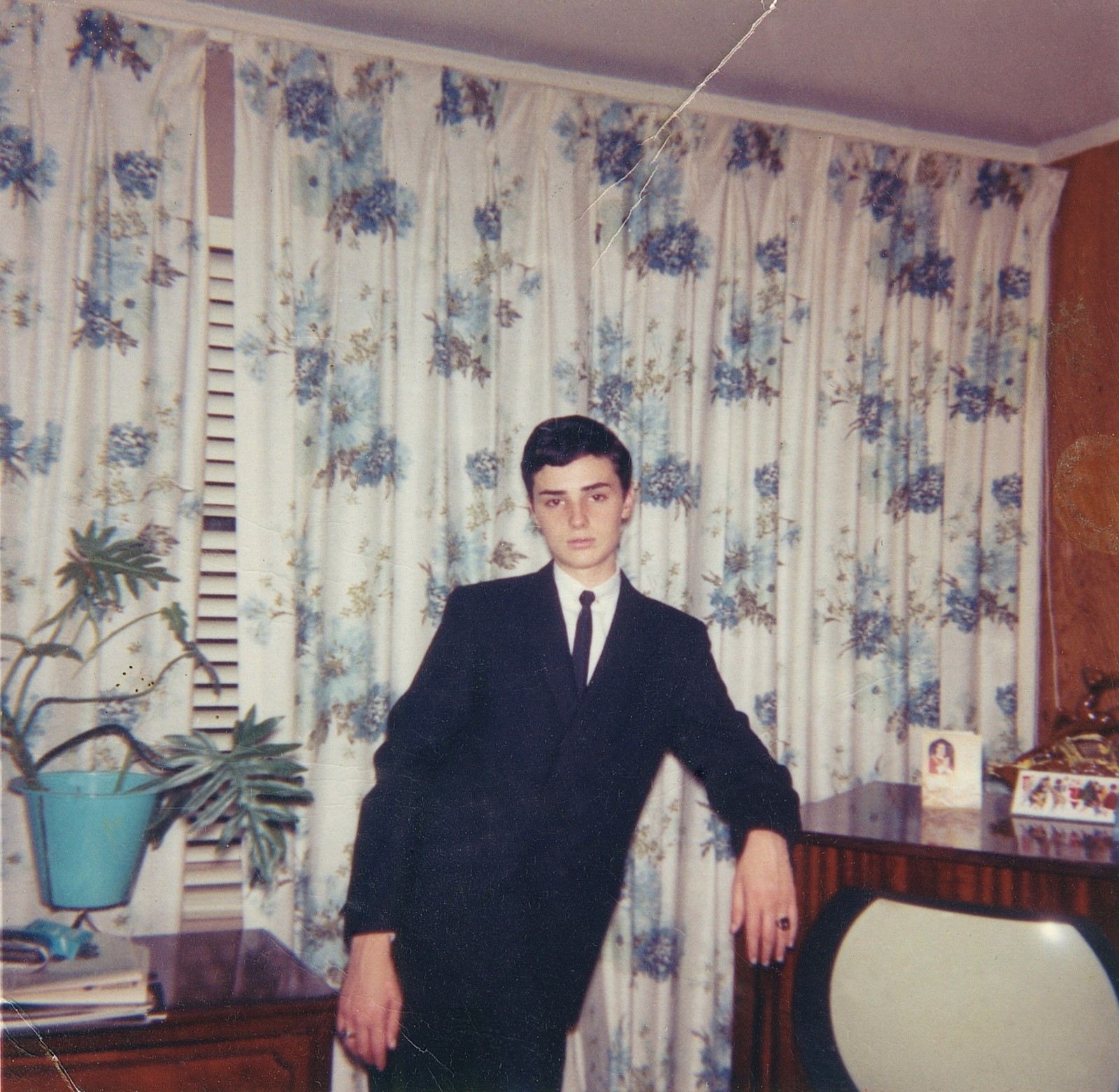

CC: I didn’t know that much about her. But I knew who she was. My main source of information was Jeremiah Newton, Candy’s friend. I haven’t even counted the interviews I did with him. I know that the total transcript is longer than the entire book. When I first met him he showed me some of her things he had in a dresser drawer – journals, letters and photos. Plus he had things of hers scattered through various boxes in his house. Everything was jumbled together, so I had to sort through all that.

It was actually more of a challenge to write about Candy than about David. It was so much harder to find the information. She never even had a place to live. She would stay with friends or go to her mother’s house. So her stuff is scattered all over the place. Even more so now. Jeremiah just died in November. He’d already sold things and put things in archives. But a lot of her stuff is just gone now. It’s in a landfill.

TW: What also makes the book so vivid is the voices from your interviews, and also the writing you quote from the time.

CC: I interviewed close to 100 people. Jeremiah had also done interviews back in the 1970s. After Candy died in 1974 he decided to write her biography. He interviewed something like 45 people. But he never wrote the book so he gave me all the tapes. Those were hugely helpful because most of those people had died by the time I started [in 2013]. Like the woman who ran the beauty parlour where Candy worked as a teenager. Candy’s mother. Various Off-Off Broadway directors like Tom Eyen. It was really valuable.

I also went to various archives. I went through old issues of the Village Voice just for a sense of context from when she started performing in 1967 up until her death in 1974. I looked at every page. Because in a way I think of the book as a cultural history of that period in New York. It’s the beginning of Off-Off Broadway. It’s the beginning of second-wave feminism. It’s the beginning of the gay rights movement. All those things are happening.

“I think of the book as a cultural history of that period in New York. It’s the beginning of Off-Off Broadway. It’s the beginning of second-wave feminism. It’s the beginning of the gay rights movement” – Cynthia Carr

TW: You argue very early on in the book that Candy predates many of the conversations about gender going on now.

CC: At that point, trans people didn’t have a place in the gay movement or the women’s movement. I was part of the feminist movement back in the 70s. We were just starting to ask questions about gender. And we thought we had it all figured out. [Laughs]. But we didn’t. I think that now we’ve figured out that maybe feminism should be about rejecting the gender binary. People weren’t thinking that way back then.

TW: Candy herself was largely apolitical. She never voted. She wasn’t part of those movements. But you make the point that her very existence was political and radical.

CC: I do wonder if she would have changed her mind if she’d lived longer. She had just turned 29 when she died [of cancer]. Maybe she would have started thinking differently. But she didn’t see herself as part of the gay movement or the women’s movement. But she was. I think her presence allows us to ask questions about gender. What does it mean to be feminine? Does your gender require a certain look and why? Things that we could ask now but weren’t asked then – or at least not very much.

TW: Did anything you found in your research really surprise you?

CC: One thing that was unusual to me was her interest in Christian Science. She never talked about it, it was only in her journals. All this interest in other esoteric forms of religion that I call metaphysical. It’s about how you can control your body with your mind. She believed in God. She was born a Catholic but that wasn’t going to work. So she was trying out other approaches of how to have faith.

I have Candy’s copy of Mary Baker Eddy’s book Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures. It took me many years to find it. It’s filled with her underlinings and notes written in the margins. She really studied it. And Jeremiah told me that she would carry it with her everywhere. In this book, I found a passage where Eddy is talking about the two genders. And Candy has written, in pink ink, “only two? I think more than two exist.” That’s the most I ever found of her talking about gender. In everyday life, she did not go there.

TW: There’s a wonderful quip from Candy you quote in the book: “My business is not acting. My business is the Candy Darling business. This I built myself.” It encapsulates this paradox you write about, that Candy’s true self was also very much a performance.

CC: There’s a theatre director called Joseph Chaikin who wrote that when you’re an actor you put on a mask, but sometimes the mask turns into your face. I think that happened with her. She developed this persona and she became it. For me, it was a very tricky thing because I don’t think she was acting all the time. But she was also so guarded. I had to walk a line there. But she wasn’t a phoney. She couldn’t have been. She lived that way all the time.

TW: You’ve spoken already about the terrible treatment she had to endure all through her life, a life that was fabulous but also very disturbing. The question I had when finishing the book is: how we can do right by her now?

CC: It’s why I choose to write the things I write. The first book I ever wrote was about a lynching that happened in my father’s hometown in Indiana. There’s a very famous picture of it that most Americans have seen: two men hanging from a tree and all these white people standing below. One’s pointing at the dead bodies. And they’re celebrating. That was the big question of that book. How do we do right by the people who were lynched?

One thing I found when writing that book was from a Chilean writer called José Zalaquett. What he said was “truth does not bring back the dead but releases them from silence.” You can’t bring people back from the dead. You can’t make it better for them. But you can make sure that people know about them, that people know what happened. That’s important. To say what happened. It’s a way of getting justice for them. That’s what draws me to the people I write about. Mostly they’re marginalised and going against the grain. I want their stories out there.

Candy Darling: Dreamer, Icon, Superstar by Cynthia Carr is published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux, and is out now.