In her new film with Mark Obenhaus, the All the Beauty and the Bloodshed director profiles reporter Seymour Hersh, whose Pulitzer prizewinning work has uncovered more than half a century of American impunity

The opening seconds of Cover-Up show footage from a 1968 news report in Utah, after a US Army nerve agent killed thousands of sheep at the Dugway Proving Ground. Institutional recklessness and an absence of accountability haunts the scene, themes that recur throughout the film – a thorough and occasionally spiky profile of investigative reporter Seymour Hersh.

In addition to exposing America’s chemical and biological weapon programmes, Hersh was responsible for several pivotal feats of journalism across the last half-century, most notably for uncovering the My Lai massacre in Vietnam and his reporting on the Abu Ghraib torture scandal. Oscar and Golden Lion-winning filmmaker Laura Poitras has always been drawn to his dogged, unflinching ethos.

“That kind of outsider adversarial counter-narrative, I mean, I make films about people who do that,” Poitras tells AnOther over Zoom. “I've also been an outsider, maybe not so much in documentaries, but doing the Snowden reporting, I brought a big story to [the press] and they were like, ‘Why are we working with a documentary filmmaker?’ It was coming from a more independent perspective that is not unlike how Sy broke the My Lai story.”

Deep into his 80s, Hersh is still a towering figure of integrity, a lively presence in a documentary he’s still not convinced he should be making. Both of Cover-Up’s co-directors – Laura Poitras and Mark Obenhaus – have a little history with Hersh: Poitras, whose previous subjects include Edward Snowden in Citizenfour and Nan Goldin in All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, wanted to make a film with him 20 years ago, but he “politely declined”. A few years ago, Hersh recommended she speak to Obenhaus, a multi-Emmy award-winning filmmaker with whom he was already discussing a collaboration.

For Poitras, a major benefit of telling Hersh’s story on film was the potential to use great archive material: the range of newsreels, documents, photographs amassed by “Sy” and about him was overwhelming. “Without the archival, I wouldn't have been the right filmmaker,” says Poitras. “I needed to know that I would be able to bring this history to the screen in a way that I felt would be unique and cinematic. We wanted to find images that, if we were shooting narrative fiction, we would be like, ‘Oh, that would be a great shot,’ like [...] where you see the death of the sheep in Dugway. There we had the actual military plane, that’s the actual nerve gas being dropped on those sheep. That’s the kind of material I need as building blocks.”

Working with archival researcher and producer Olivia Streisand, the documentary amassed 7,000 different assets covering Hersh’s life through decades of American politics, which the filmmakers wanted to craft into something memorable. “We were interested in showing the context of the archival. Like if you have an article that Sy sees about [William] Calley [the only US soldier convicted for the My Lai massacre], [we’d want] to show the advertisements that were around it. We’re interested in those juxtapositions, but I was also hesitant. Sometimes you get archival material and it has a bit of a kitschy vibe. Like the commercials – if we were to take a commercial that was juxtaposed with Sy doing an interview, then there’s a kind of vernacular that isn’t what we wanted. We wanted something that had a simmering political thriller vibe.”

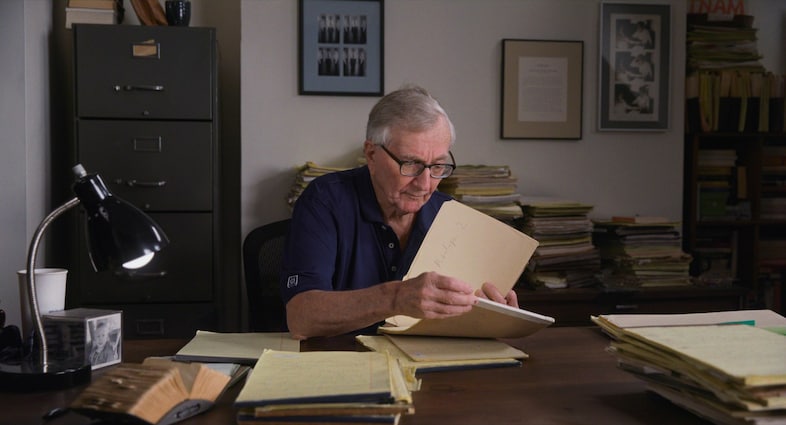

Hersh is a generous but sometimes tricky interview subject, firmly planted behind the desk in his home study and, more than once, answering phone calls in the middle of a take to discuss ongoing articles. (These days, he’s moved to Substack.) “People often say [he has] boundaries, but he was also the most generous,” says Poitras. “We did 40 interviews. He was always game to try to answer every question we asked. Sometimes he would get frustrated. He’s protective of his wife as a psychoanalyst, and he’s been a public figure for a long time. So there was a protectiveness, which I understood. I wasn't interested in biopic beats, but I am interested in what makes him tick and what informs him.”

Again, she felt most drawn to artefacts around him, symbols of his journalistic prowess. “I always thought that the notebooks on his desk were these ways to transition into the past, kind of portals into history.” In one memorable moment, Hersh gets agitated about documents in the filmmakers’ possession and demands that filming stop – not just cutting the cameras, but terminating his participation in the project entirely. This friction gives an insight into Hersh’s unsteady relationship with the filmmakers, which Poitras says she was always hoping for.

“Sy’s protectiveness about being interviewed starts to play like a scene, not just him narrating. The scene that’s at the beginning, it’s probably the second day of shooting, where he’s like, ‘I’m not going to be psychoanalysed,’ and ‘these people are still alive’, and ‘What are you asking me?’ I think that that’s just telling the audience about his protectiveness over his work. He’s generous in his resistance, in a way that I really appreciate[...] When he decided that he’d had enough, he was directing a lot of his frustration at me, and it was definitely an intense day. [But] I felt confident it wasn't going to be the end of the movie, because we’d already been scrubbing [through the archival clips] for a year. It could have been the end of Sy in the movie. Luckily, it wasn’t.”

The scope of Cover-Up extends to some of the most well-documented scandals and abuses of institutional power in the US, but Poitras thought that “with Sy as a lens”, they could say something unique about America’s “patterns of impunity”. “People have asked, ‘Why not a multi-part [series]?’” says Poitras. “You could, but then you’d have just one segment of history [per episode]. I wanted the cross-connection. I wanted to be able to cut from My Lai to Gaza, to his family, and say something different about history.”

“I feel like one of the reasons we are in the historical moment we're in right now in the US is because we don’t reckon with atrocities when they happen, and that sets the stage for them to be repeated. America is a country that has a problem with amnesia. We’ve done screenings where people have brought 18-year-olds [along], and they didn’t know about the Abu Ghraib torture. To me, this is shocking, so it’s somehow a way to say that the trauma continues.”

Cover-Up is on Netflix from December 26.