Writer-turned-filmmaker Durga Chew-Bose talks about her adaptation of Françoise Sagan’s beloved 1954 novel, starring Chloë Sevigny and Claes Bang

“When I can’t write, I watch a movie,” wrote Durga Chew-Bose in an essay from 2019. “When I can write – irrespective of whatever quick rhythm or new stuff is developing on the page – I watch a movie.” This summarises the writer-turned-filmmaker’s symbiotic relationship to movies – a reverence for granular detail, and a devotion to a distinct visual language. How a film looks is just as important as how it feels; style and substance coexist. It’s an instinctive approach that seeps through her directorial debut, Bonjour Tristesse, a modern adaptation of the beloved 1954 novel by Françoise Sagan.

“When I wrote that piece and sent it to [my editor], he was like ‘Where does this come from? This is the most you thing,’ Chew-Bose says from her home in Montreal. “I mention that because the refrain ‘This is the most you thing’ has been a throughline for our adaptation of Bonjour Tristesse in that … the references and the films I watched, especially with my cinematographer, Max [Pittner], weren’t necessarily Éric Rohmer films or sun-speckled, south of France, beach setting films. They were films that felt evocative to us, and we tried to trust that even if we didn’t know why there was a link happening, we should pursue it.”

Perhaps you have read the novel, or watched the Otto Preminger-directed version. For the unfamiliar, the story centres on a teenager named Cecile (played now by Lily McInerny), whose entanglement between her widowed father, Raymond (Claes Bang), his partner Elsa (Nailia Harzoune), and his wife’s friend, Anne (Chloë Sevigny) sets a sleepy, coastal summer in motion. It’s as much a coming-of-age narrative as a study in relationship dynamics, how they bend and break.

Chew-Bose cites Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day, the films of Lucrecia Martel, and early 2010s blockbuster Moneyball as inspirations. She quips, “As a joke to Max, I would be like, ‘I want to have a Moneyball shot in the film,’ but that mainly meant seeing the nape of a man’s neck with a bit of a chain.” The influences indicate Chew-Bose’s knack for observation, finding the perfect frame in the most unassuming of places. A line in the film: “Everything is about listening.”

She was approached by producers Katie Bird Nolan and Lindsay Tapscott to write the screenplay (and eventually direct) after the release of her essay collection, Too Much and Not The Mood, and despite not having a strong personal connection to the source material, Chew-Bose embraced making it her own. “I think it was a necessary step towards some semblance of confidence,” she says. “I also think you need a lot of focus when you’re making a movie. The number one way to lose focus is to let too many voices in your head. There’s a part of us that – as a team – just had to trust-fall into this new version. I think that sort of distance was ultimately more generative for me in terms of adapting it.”

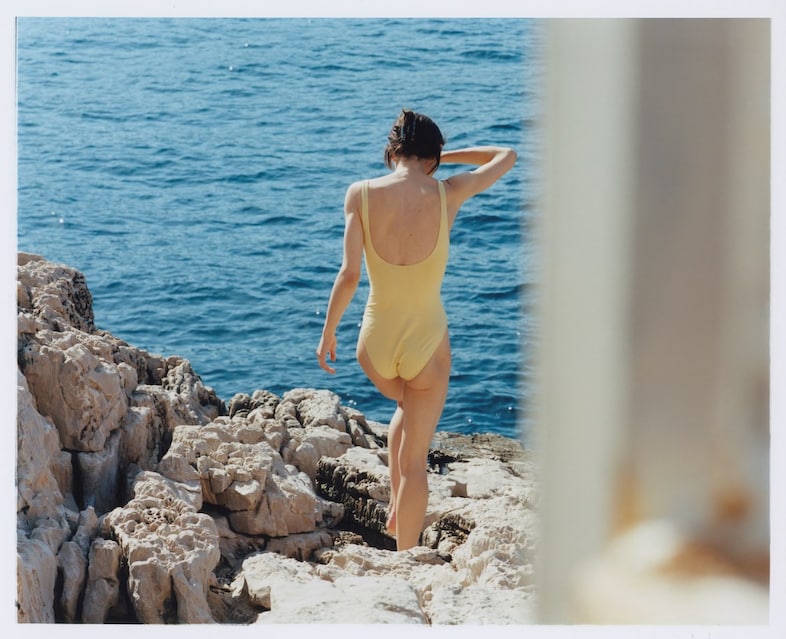

Chew-Bose’s description of making the film is alchemical. The crew landed on the picturesque town of Cassis in the south of France as a location – it was the first place they saw and is rarely used for filming; Chew-Bose immediately loved it. There was trust and a shared vision on set, too, especially around costuming. Chew-Bose enlisted Miyako Bellizzi, whose credits include Uncut Gems and Good Time, to outfit the characters. She selected accessories and clothing for Sevigny and McInerny from Sophie Buhai and Renaissance Renaissance – a cult-favourite brand whose feminine silhouettes range from formidable (Anne’s tailored suits) to playful (Cecile’s silk party dress, which she wears sitting on the floor at midnight in front of the fridge, having a snack). Sevigny’s Anne keeps her tight buns secured with a shiny silver hairpin, while Cecile rotates between a yellow one-piece swimsuit and striped tee shirts (her hair is often wet). A sweater is tied around her shoulders one night while outside with the grown-ups.

“Something that Miyako and I talked about a lot: [Cecile’s] a woman, but she doesn’t spend a lot of time with other young people on this vacation,” Chew-Bose explains. “Cecile has this mix of elegance and grace and feral wildness. Either she’s in ballet flats or barefoot. She’s never wearing pants, or she’s wearing her dad’s shirts. I think that Miyako really wanted to create this world where everyone had only packed a small suitcase.”

It’s her tendency to create work that is at once expansive and contained that makes the film so intriguing. Naturally, adapting a 71-year-old text could threaten this dichotomy with modernity. Cecile uses her cell phone, sure, but it’s as much a natural part of her as her penchant for collecting shells (a detail that Chew-Bose added in due to McInerny’s interest in mudlarking). Cecile takes pictures of herself, then the moon.

“I think it’s a mistake to try to make a contemporary story and hate technology,” Chew-Bose says. “I don’t think phones are ugly. Cecile is a really interior person, and I didn’t think that interiority meant that she was on her phone. It’s how she’s a voyeur in her own household, or how she watches other women and takes notes. Then, taking photos of the moon – it almost had nothing to do with the phone, it’s more [about] how you can never really capture the moon.”

Movie-making is a risky business. But her commitment to world-building, to getting that perfect shot, is propelling Chew-Bose forward. “Movies are just my favourite thing in the world, nothing makes me happier really,” she says. “But now I truly understand how it’s a miracle that any movie gets made.”

Bonjour Tristesse is out now.