Considered by critics as one of the greatest directors of all time, Edward Yang was a pioneer of Taiwan’s New Wave movement. Here are four films you can watch now

If he were still alive today, November 2021 would have marked Edward Yang’s 74th birthday – but as fate would have it, Taiwan’s greatest filmmaker wouldn’t make it past 59. It was in 2007 that the director died from cancer, seven years after the completion of his final masterwork. But he leaves behind a legacy that remains fascinating, enduring and highly decorated, with his films regularly cropping up on critics’ all-time “greatest” lists.

Born in Shanghai and raised in Taiwan, Yang grew up watching the films of Federico Fellini and Robert Bresson, before taking influence from the works of Wim Wenders and Werner Herzog while studying and working in America. It was at this point of revelation that he chose to pursue filmmaking, during a time where Taiwan was in the midst of significant economic and social transformation.

Alongside compatriot Hou Hsiao-hsien, Yang was a progenitor within the brief but impactful New Taiwanese Cinema movement in the 80s. The movement rejected the popular escapist fantasies common in Taiwanese cinema at the time, and was instead determined to reflect local society and culture – under the banner of “creativity, artistic quality and cultural self-awareness,” as outlined in the 1987 ‘Taiwan Film Manifesto’. But Yang, in particular, is regarded for his concern with city living and the urban environment, with familial relationships seen as a microcosm for the changing society. Deliberate pacing, a novel-like density, rich, smoky colours and a meticulous mise-en-scène, meanwhile, are the hallmarks of his perfectionist style.

Yang’s spellbinding vision and humanistic tendencies pushed Taiwanese cinema into a new era in the 90s, best exemplified by the increased presence of Taiwanese films at Cannes Film Festival between 1994 and 2000 (during this period, Yang and Hou’s films were nominated for the Palme d’Or a total of six times). It’s a feat that bears relevance today, as Taiwan is, once again, in the midst of transformational turmoil as tensions flare with the Mainland. The nation’s cinema, on the other hand, could be on the cusp of newfound international attention, as the decline of the former powerhouse industry of Hong Kong points to a rebalancing of the East Asian film market.

With restored versions of Yang’s masterworks recently screening at the London East Asia Film Festival in October, and at London’s Close-Up Cinema in November, it seems a fitting time to revisit this dearly beloved filmmaker’s canon. Find the four emphatic films below via Criterion Blu-ray and on streaming platforms, and experience one of the most sumptuous directors in the history of East Asian cinema in all his glory.

Taipei Story, 1985

Two people gaze silently from the window of an empty apartment in the opening of Taipei Story, and a sense of longing is established in an instant. The couple is Lung (played by director and co-writer Hou Hsiao-hsien), a former baseball star whose family have emigrated to America; and Chin, who is forced to take a mundane secretarial job for which she is overqualified after the construction company she works for is bought out. What begins as a story of endurance in a time of rapid transformation soon becomes a study of the slow decline of a relationship. As the couple hopelessly cling to past glories, their dreams and ambitions begin to unravel.

One scene finds Chin advised by her former employer to leave her position if she gets a better offer, as a steady flow of cars moves past outside the window. Another finds Lung pull up in traffic at a busy crossroads in the cosmopolitan chaos of the city centre. Elsewhere, a kaleidoscope of colour is observed at a busy nightclub, where young revellers dance wildly to Kenny Loggins’ Footloose – directly contrasting a shot circling a lit-up monument that reads ‘Long Live the Republic of China’. The quest for belonging rears its head at every beat.

It’s one of the first examples of the Taiwan New Wave movement seen in action, and the film remains a visual delight, thanks to the smoky glow of orange car headlights, the wavy flicker of televisions, and the colourful neon signage of Taipei city. In 2016, a 4K restoration was funded by Martin Scorsese’s Film Foundation for release via the Criterion Collection; it was screened in full glory at the London East Asia Film Festival this October.

Terrorizers, 1986

The lives of several city-dwellers become intertwined in this dazzling and enigmatic drama set, once again, in fast-modernising Taipei. Among them: a female novelist and her hospital researcher husband, a voyeuristic photographer, and a rebellious young woman who scams clients while working as a call girl. Initially, their stories appear to be unrelated, but the film functions as a kind of puzzle for the viewer to piece together. Phantom narratives then emerge through the rhyming and contrasting of separate relationships and events, and ultimately, it is through these ricochets and echoes that the film’s true conclusions can be drawn.

If it sounds like hard work, be assured: like so many of Yang’s films, a brilliant use of saturated colours, intricate set design, and a meditative pace make the experience utterly beguiling. Music plays a poignant and mysterious role, too. In this film, The Platters’ emotive rendition of the song Smoke Gets In Your Eyes is evocative – the track’s title is an effective stand-in for the nature of the film itself.

The Terrorizers was awarded Best Feature Film at Taiwan’s Golden Horse Awards in 1986 – a testament to the thought-provoking power found within. Watch it on MUBI today, as it celebrates a 35-year anniversary since its release this December.

A Brighter Summer Day, 1991

In December 1949, the Kuomintang (Chinese National Party)-led government of the Republic of China lost a civil war against communist forces and retreated to Taiwan, where it ruled by martial law for over 38 years. The events portrayed in A Brighter Summer Day, which is set in 1959 and 1960, bring this oppressive “White Terror” to life, in an empathetic and humanistic portrayal of the lives of fleeing Chinese Mainlanders who arrived in Taiwan as outsiders.

It is the children of these uneasy migrants who are the focus in A Brighter Summer Day. They seek a sense of identity by joining school gangs, listening to American music by artists like Elvis, and engaging in a lifestyle confused by violence, romance and uncertainty. But, as is emblematic of Yang, this is much less a character study than a sprawling, humanistic epic. It utilises meticulous set design and isolationist framing methods to minimise the profiles of groups and individuals against the film’s resplendent surroundings: schools, verdant countrysides and rural towns.

The central character of Zhao Si’r is notably played by a 15-year-old Chang Chen; later known for his starring roles in the Wong Kar-wai films Happy Together and 2046, and, most recently, as Dr Wellington Yueh in Dennis Villeneuve’s Dune. He, like so many characters in this transcendent coming-of-age drama – likened to The Godfather as much as the intimate works of Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu – strives for an elusive fantasy that seems beyond his reach; the “brighter summer day” of the film’s title.

Yi Yi, 2000

At the dawn of a new millennium, Edward Yang completed his magnum opus: an extraordinary meditation on modernity and changing human values in a transitional society. Tragically, it would be his final film before he died at just 59 years old in 2007.

Yi Yi is a captivating and intricate family melodrama that explores the lives of middle-class father NJ, his young son and his teenage daughter across three concurrent narratives. The stories mirror and reflect one another: it opens with a wedding, and ends with a funeral a year later, and it is the poetry and repetition of these multifaceted storylines that makes Yi Yi so fascinating and memorable. Its sense of heart, and its extraordinary visual beauty, is infallible – so much so that its three-hour run-time floats by as if by magic.

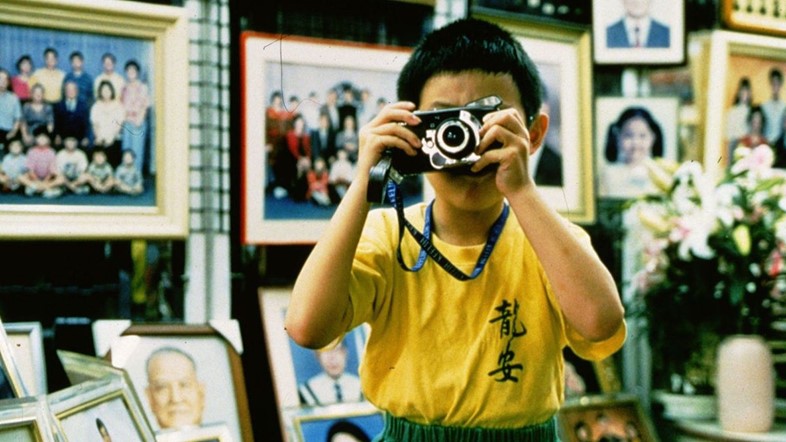

One of many prominent narrative lines is NJ’s chance encounter, and brief reconciliation, with his former sweetheart, Sherry – a woman he had stilted and abandoned in his young adulthood. It contrasts with the brief romance experienced by his daughter, Ting-Ting, captured by the repeated shot of her meeting the troublesome Fatty in a concrete underpass half-consumed by vines and greenery. All the while, mischievous youngster Yang-Yang throws water bombs at teachers and gets into all kinds of trouble, providing some touching humour opposite strands concerning illness, heartbreak and tragedy. He innocently hopes to help others see what they couldn’t before, by taking photos of the backs of peoples’ heads.

The tableaux of stories, both implicit and clearly defined, linger long after the credits roll. In the West, though, acclaim was instantaneous. Yi Yi was named the best film of the year by critics at the New York Times, Village Voice and Time Out New York in 2001, and was notably included on Sight & Sound’s 100 Greatest Films of All Time list in 2012. For this final feature, Yang competed for the Palme d’Or at Cannes – and took home the Best Director award at the same festival, becoming the first Taiwanese director to be awarded the coveted prize.