James Balmont looks back at five choice cuts from Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s catalogue that show why he remains a beacon of strength within Taiwan’s revitalised film industry

Greater Chinese cinema is in the midst of some tumultuous changes. But while the creative liberty of Hong Kong’s film industry comes under threat from restrictive new censorship laws from the Mainland, the native industry in self-governing Taiwan looks increasingly prosperous off the back of a period of rapid regeneration.

It was only 20 years ago, in 2001, that the number of films locally produced in Taiwan had sunk to just nine – dwarfed by imports from Hollywood and Hong Kong despite the growing international renown of directors like Tsai Ming-liang (Goodbye, Dragon Inn) and Ang Lee (Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon). But this nadir was sandwiched between two high-points in the country’s cinematic history: in the past decade a commercial revitalisation has seen domestic titles become box office sensations at home and on the Mainland. And prior to a late 90s slump, the 80s had seen New Taiwanese Cinema championed widely at home and at leading film festivals in Europe.

One director that has straddled the entire rollercoaster is Hou Hsiao-hsien. A progenitor of the New Taiwan Cinema movement, he cemented his reputation with a series of films in the 80s that rejected the escapist fantasies, martial arts movies and melodramas dominant in Taiwan in favour of a realistic filmmaking style deeply concerned with local culture. “Creativity, artistic quality, and cultural self-awareness,” were the cornerstones of the 1987 New Cinema manifesto, signed by around 60 Taiwan filmmakers including Hou. And though his manifestation of those values through tranquil films about adolescence, political tension and the transformation of society would be maligned as self-indulgent by native critics by the late 80s, his reputation abroad has rarely faltered.

With such a broad and captivating canon it’s easy to understand the long-standing fascination. Earlier works like The Boys From Fengkuei and Daughter of Nile had explored the struggles and anxieties of young people in a rapidly urbanising Taiwan, while A City of Sadness (winner of the Venice Golden Lion in 1989) was the first Taiwanese film to confront the “White Terror” in post-World War Two. Further afield, Hou has revelled in both the neon-lit nightclubs of Taipei in Millennium Mambo (a Cannes Palme d’Or nominee in 2001) and the countryside of Tang Dynasty China in The Assassin (awarded Best Director at Cannes 2015). And he’s collaborated with everyone from Japanese icon Tadanobu Asano in 2003’s Cafe Lumiere, to Hong Kong superstar Tony Leung in heady 1998 period drama Flowers of Shanghai – released as part of the Criterion Collection in the UK last month.

Hou’s latest, Shulan River, is hotly anticipated for release within the next year – and its success will surely test the veracity of any statement on Taiwan’s future prospects as a global filmmaking power. Until then, we look back at five choice cuts from the director’s catalogue that show why Taiwan’s most cherished auteur remains, at the very least, a beacon of strength within the nation’s revitalised film industry.

The Boys from Fengkuei, 1983

On the island fishing settlement of Fengkuei, Taiwan, waves crash against rusted boats on the shore while ramshackle homes crumble into the chipped concrete streets. Boys will be boys, even in Fengkuei – and so the four young lads who lead this coming-of-age drama revel as they tear up the roads on mopeds, get into scuffles with bigger boys, and chat-up girls on the beach.

But opportunities beyond such fun and games are limited at home – so the boys eventually set sail for the port city of Kaohsiung in search of work. There, they find themselves small fish in a very big pond: they’re collectively swindled for cash by an adult cinema tout, while one of the group quickly finds himself lovelorn after falling for a local thug’s girlfriend. Displaced and alienated, the boys struggle to set themselves on the path towards a stable adulthood.

This crucial early film bears a synergy with Hou’s own childhood, which was partly spent with street gangs in rural Taiwan as he navigated the uneasy transition from post-school-age to adulthood. More significantly, it marks a partial genesis of the director’s style – particularly his tendency to emphasise natural environments in fixed long-shots – at a time when the New Taiwan Cinema movement was just beginning to disrupt the wider film industry.

Daughter of the Nile, 1987

The Boys From Fengkuei had incorporated personal experiences from Hou’s youth, while 1985’s The Time To Live and The Time to Die was literally shot in the house the director grew up in. But Daughter of the Nile took a step away from the biographical and autobiographical works that had preceded it, as the director sought to instead explore the inherent concerns of young people growing up in then-contemporary Taiwan.

Against a backdrop of modern, synthesised Chinese pop music, pop singer Lin Yang plays Lin Hsiao-yang, an honest young woman in a mismatched family, living on the edge of a fast-changing Taipei. By day, she works at KFC under the warm orange glow of fast food heat lamps; by night, she attends night school before becoming consumed by the moody blues and neon pinks of the strip’s coffee houses, bars and nightclubs. Her brother, meanwhile, is a gambling street hoodlum evading armed thugs in a city where profit and prosperity has become the arch motive of those stimulating its evolution.

Not everyone is affected positively by these societal changes, and the film’s cut-up chronology mirrors the scattershot fortunes of those caught up in the tumult. The greater meaning of the rich images on screen remains relatively elusive and cryptic until the end, but one potent attribute is atmosphere of longing that transcends the screen – best embodied by the distant, repeated scenes of Lin’s family around a dinner table at home, shot through the arch of an opposing doorway.

The film, a transitional work for the director, was initially seen as a misfire – though popular opinion has U-turned in the wake of the film’s re-release via Eureka’s ‘Masters of Cinema’ imprint.

Flowers of Shanghai, 1998

“The most elite pleasure quarters in late 19th-century Shanghai lay hidden in the city’s British concession,” begins Hou’s 1998 masterpiece – his first set outside of Taiwan. Captured almost entirely in the soft, orange light of oil lamps within the confines of the titular “flower houses”, Flowers of Shanghai duly unfolds at a languid pace, as a series of romantic encounters envelops the patrons of a series of high society brothels.

In spite of the conducive setting, Flowers of Shanghai is a film almost entirely absent of sex and fornication, with the focus applied instead to the complex emotional links binding men and women. With less than 40 shots comprising the entire narrative, this claustrophobic haze of lust, love and deceit is as intoxicating as the billowing opium smoke that regularly fills the screen.

What begins as a hypnotic depiction of 19th-century gossip and hedonism is lent great nuance as themes of trust, dominance and fidelity increasingly mirror the anxieties of present-day society. Indeed, much like historical drama A City of Sadness (1989), this preoccupation with a period of greater Chinese history can be seen as a means to better understand contemporary Taiwanese national identity.

Sumptuous costumes and an emphatic set design are married by a transcendental score played on traditional Chinese strings, brass and percussion, while dazzling performances by superstars Tony Leung and real-life partner Carina Lau are as hypnotic as the hovering camerawork. No surprises, then: it was selected to compete for the Palme d’Or at Cannes, and selected as Taiwan’s entry for Best Foreign Film at the Oscars.

Millennium Mambo, 2001

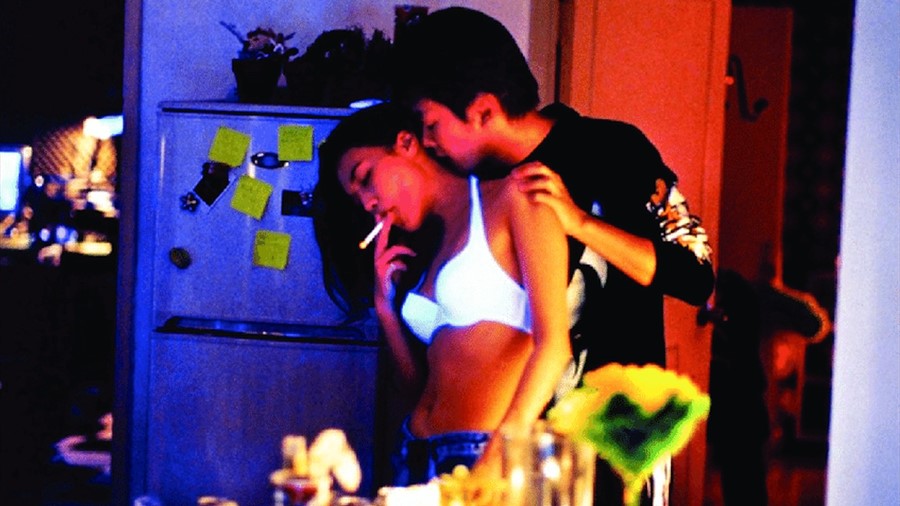

While Daughter of the Nile was a portrait of a transitional mid-80s Taipei, Millennium Mambo observes the ultra-modern side of the city some 15 years later through the eyes of a woman trapped inside a personal hell. Shu Qi (The Assassin) plays the troubled lead Vicky, a high school dropout living aimlessly with her abusive, unemployed boyfriend Hao-Hao in the city. She dreams of leaving him for a better life, but no matter how many times she tries he always wins her back.

Much of the film takes place inside the city’s bustling, neon-soaked night clubs, where the UV lasers, colour-clashing rave-wear and a constant, throbbing techno soundtrack emphasise Vicky’s entrapment. Even at home, she is overwhelmed in shots by cheap booze, Y2K drug paraphernalia and Hao-Hao’s wired sexual advances. Her only respite comes courtesy of a brief, spontaneous sojourn to snowy Hokkaido, in Japan – where beats, bass and bright lights are momentarily replaced by rural vistas and a frosty ambience.

While starkly contrasted to his age-spanning historical dramas, Millennium Mambo is, perhaps, Hou’s most evocative tale of troubled youth – and certainly his most vibrant. But the bold colours, intoxicating soundtrack and tantalising camerawork (the opening scene, which follows Vicky in slow-motion through a foot tunnel as a thumping beat draws closer, almost feels like it’s sucking the viewer into a vortex) also draw fascinating parallels with Hou’s previous work – the pre-modern Flowers of Shanghai. It’s a reminder that, at the heart of his films, it is a fascination with humanity that often speaks the loudest.

The Assassin, 2015

In the hands of another director, this 8th-century story of an assassin tasked with slaying a military leader could have been portrayed with gung-ho action and chivalrous heroism. With Hou – who was nominated for a Bafta after winning the Best Director prize at Cannes for his work – it is instead an exercise of pure, balletic wonder.

The dialogue is minimal, with the film instead punctuated by the sounds of creeping footsteps and crickets. The aspect ratios and colour schemes evolve throughout, as scenes switch from opulent palaces and temple rooftops to verdant green forests and mountain silhouettes. It is a slow, deliberate film – the product of a determination by the director and cinematographer to find a new angle in martial arts cinema. They did succeed in this aspect, binding lush realism with the magic of classic martial fantasy.

The film was shot by Mark Lee Ping-bing – a Cannes Grand Technical Prize winning photographer favoured not only by Hou (whom he partnered for Cafe Lumiere, Flowers of Shanghai, and Millennium Mambo, among others), but also Wong Kar-wai (In The Mood for Love) and Hirokazu Kore-eda (Air Doll). It is his camerawork that, so often, has given Hou’s work such a magnetic and transcendent visual quality, and with The Assassin – to date Hou’s most recent feature – he might have achieved his zenith.

“When we feel the wind rising,” Ping-bing tells viewers in the Studio Canal Blu-ray for the film, “we let the cameras start rolling, so the visuals can speak for themselves.”