In a corner of Amsterdam (5 Spinozastraat, ground floor, to be exact) in 1943, a cancer researcher was part of the last large-scale deportation of Jews to leave the city, mere months after two of his children were killed in concentration camps. Today, the house is someone’s office, and a child plays a video game, and there are rabbits held in a hutch outside. In another corner (1 Paleisstraat) in 1945, German soldiers shot at Dutch people celebrating their liberation in the square. Now, a toddler runs after pigeons, and a Palestinian banner demands an end to the apartheid wall.

In Steve McQueen’s Occupied City, his monumental account of Amsterdam during the Second World War, a single voiceover narration recounts the past while the present plays out before our eyes; the unfathomable events of the Nazi occupation and Holocaust set against the tumultuous news cycles of the early 2020s. Based on Dutch filmmaker, frequent collaborator and wife Bianca Stigter’s book Atlas of an Occupied City, Amsterdam 1940-1945, which takes a minute, cartographic approach to the history-drenched capital, Occupied City – directed by McQueen, written by Stigter – is a work of astonishing scope. Points of crisis overlap, seemingly in conversation, although the details of this dialogue remain opaque. Rather than trading on easy analogies, McQueen and Stigter peel back the layers of Amsterdam to reveal it as the dense artefact it is, inscribed in palimpsests of violence and memory.

Closer in some ways to an art piece than many of the films released in cinemas today, Occupied City is intended as an invitation to contemplation rather than education. The facts are laid out before you, the strange, ghostly juxtaposition of genocide and a still living, breathing city, but the conclusions are your own to draw.

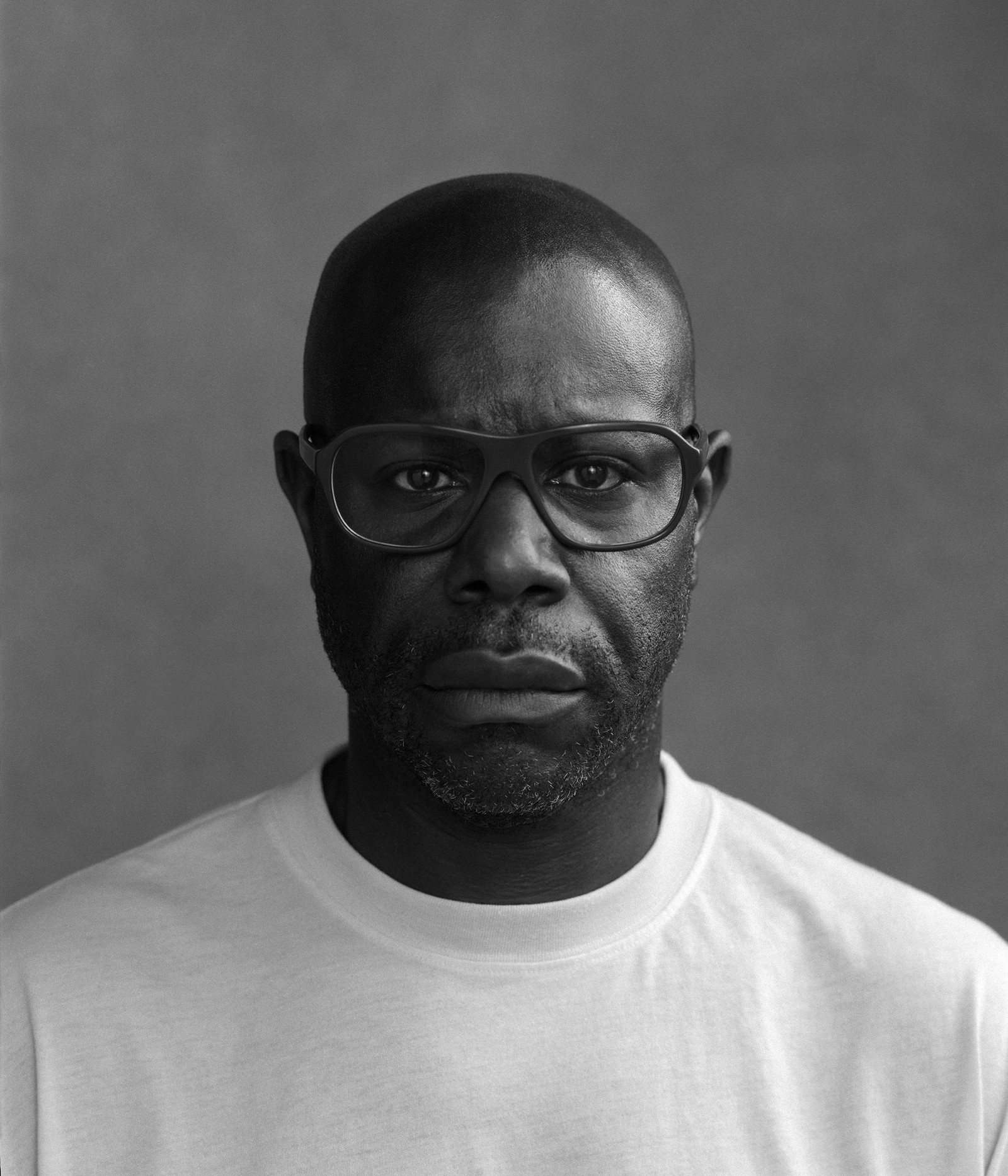

We sat down with Steve McQueen and Bianca Stigter to talk about the language of the archive, the limits of memorialisation, and why – sometimes – there are no easy answers to be had.

Anahit Behrooz: I’m curious what initially drew you both to this subject, and what made you decide to adapt Bianca’s book into a film?

BS: I started writing out of curiosity, because Amsterdam is a city where some parts of history are very visible. The canals speak of the 17th and 18th centuries, other places the 19th, but you cannot see [the Second World War] in the city. Of course, there are monuments but only for the most important events. But I wanted to know where the Germans [and] resistance groups were, where the Holocaust was organised. I was trying to make a kind of time machine on paper, [which] tells you neighbourhood by neighbourhood, house by house, sometimes floor by floor, what happened during the war. Of course, it is an illusion that you can capture everything, but I gave it a good shot.

SM: Being in Amsterdam is like being in an archaeological dig because you’re seeing viewpoints that Vermeer saw, that Rembrandt saw: it’s a 17th-century city that was never bombed. So every time I walked around, it was like projecting the past onto the present. And I thought, ‘What if I got some footage from 1940 and traced that film footage onto now, and have the living and the dead in the same frame?’. But [while] I was trying to find some footage I heard the tapping of keys in the next room, which was Bianca writing the past. And I thought, ‘What happens if the now is the now, but with the text of the past on top?’

AB: The film takes these archival events from your book Bianca, and sets them against these contemporary moments of crises – the pandemic, COP26. I’m interested in this language of juxtaposition – how did you want these periods to speak to each other?

SM: They speak to each other because they happen to be under the moon, the stars and the sun. They happened under the umbrella of the universe in different time periods. You know, you have, for example, two curfews: there was a curfew during the Second World War to prevent British and American bombers and also to curb any kind of resistance, and of course we had a lockdown curfew. [But] these two ideas are North Pole, South Pole. They’re two different things. There have been people who have tried to join the two things, but it’s like making sense out of nonsense. And that’s the world we’re living in. You know, try and make sense out of six million people being murdered. Go ahead!

BS: We’re not comparing. We’re showing you things that happened in the same location, and if anything, it proves how different they are. Yes, on the surface, you might have some similarities, but for the rest, the film proves that there are vast differences.

SM: Unfortunately, it’s not maths. It doesn’t make any sense.

“It’s not a history lesson. It’s an experience that you have to undergo, a kind of meditation on the past and the present and the way they are connected, or not” – Bianca Stigter

AB: I’m really interested in this idea of a city as an active rather than passive entity – it has a lifeblood. To what extent do you see cities as active participants in history rather than mere backdrops?

BS: I think there’s a very active part for the viewer, because you hear what happens in a certain location and you see what is happening there now, and it’s for you to make a connection. But this film shows you that sometimes the connection is not easy to make. It’s not a history lesson. It’s an experience that you have to undergo, a kind of meditation on the past and the present and the way they are connected, or not.

SM: I think it is very important to say this is a meditation and not a history lesson. We’re not moralising. But at the same time, you project your own history onto [the film]. It’s like going to a classical concert, where you’re in it but you could never hold all the notes together. It is so vast, and I think that tells you about the sort of atrocity that went on. I think how [the voiceover actress] Melanie delivers the text is very important. It’s not dispassionate, but it’s also not manipulative. She’s not the voice of authority [or] the voice of god, as in most documentaries.

BS: She’s just one step in front of you on this walk through Amsterdam. It is a voyage of discovery you are on together.

AB: You said this isn’t a moralising film. Do you see it as an act of memorialisation?

SM: No, I don’t think so. There’s no dust on this picture. I’m not interested in that. It’s active, it’s muscular. It’s not a statue. It’s much more mobile than. Forgive me for saying this, but I think it fucks with your head a little bit.

BS: I think for me it is a memorial of a certain kind, in that I feel an urge that these things be remembered, and soon they cannot be remembered by the people who lived through it. But they can be remembered by us. I think it’s both things.

SM: I suppose for me it has much more motion. The way I see a memorial is a kind of pause. Ours is living.

Occupied City is out in UK cinemas now.