From the reissue of MFK Fisher’s 1949 food classic An Alphabet for Gourmets to Darryl Pinckney’s account of the New York literary world; here are the best books to curl up with as the days get shorter

Now that it’s finally cold enough to register as a new season – and becomes dark by 5pm – my monthly ‘have read’ list will go way up. Here, I’ve selected six new (or new-ish) books that excited me, with obvious themes that repeat. I am endlessly fascinated by families, and by the way in which, for the nuclear or ‘normal’ family to be preserved, different personalities, realities, and memories must be sanded down in such a way that conflicting versions fit within the whole. Several of these books are explorations of when that doesn’t happen. Some seem to ask the question: can you undo a life? Where others are minutely considered by the ways in which, through things like objects and food, we furnish our identities.

Love Me Tender by Constance Debré (lead image)

Love Me Tender opens with Constance Debré meeting her ex-husband (at this point they’ve already been separated for three years, though not yet divorced) to tell him she has started seeing women. In the brutal divorce that ensues, he shuts down almost all contact between Debré and her then eight-year-old son, Paul, using false accusations of paedophilia to block custody.

In many ways this is a book about aftermaths; of decisions, accusations, and the aftermath that is parenthood itself. Debré yearns for her son – like a grieving parent she even structures her day to avoid school children – but in the same breath, she acknowledges that his absence gives her a certain freedom. She begins to dismantle her life. Renting a tiny flat, she leaves all her remaining possessions on the street outside. “I watched it all disappear from my window, it was amazing, the little ants of the 6th dissecting it all, collecting it all up.” A compulsive read, this is for fans of Virginie Despentes, Hervé Guibert and Guillaume Dustan.

Living Rooms by Sam Johnson-Schlee

I was won over by Living Rooms early on, when a preliminary flick through it revealed chapters called simply ‘Velvet’ and ‘Chintz’. Dedicated to Galvey, the ramshackle house Johnson-Schlee’s maternal grandparents lived in post-retirement – to which the writer, his mother and brother also moved after his parents separated – this is a study of living spaces and their meaning. “Galvey is a record of years, it is a family member, and it is its own memoir,” he writes.

A moving consideration of interiors, Living Rooms is filled with pleasingly eccentric notes and digressions. One paragraph begins, “As a child, I hated ET (1982).” Or on sofas: “I like a sofa that is so comfortable it makes me forget about my body. Like sensory deprivation, a good sofa suspends time.”

Is Mother Dead by Vigdis Hjorth

Vigdis Hjorth’s 2016 novel Will And Testament caused a sensation in her native Norway, perceived by some as an autobiographical account of the trauma of childhood sexual abuse, stirred up by a squabble over a will. Though Hjorth has always maintained it is a work of fiction, family members denounced the book, with her sister even writing a retaliatory novel, Free Will.

Hjorth’s latest, Is Mother Dead, cleverly plays on this context. Johanna, the narrator, is a middle-aged artist long estranged from her parents and sister, an estrangement ostensibly brought about by a series of paintings in which the family was depicted negatively. (Cleverly, again, we never get a full sense of what the paintings actually show – we get only Johanna’s perspective throughout the novel.) Recently widowed, she returns to Oslo from the US and begins, slowly at first, to stalk her mother. Brilliantly claustrophobic, this novel is a testament to the fact that, when the present becomes the past, we are only left with our own version of what happened.

Sea State by Tabitha Lasley

I bought this book in June immediately after reading Lasley’s startling Guardian essay, Cocaine, class and me …, then it sat unread on a shelf for months because I didn’t like the cover. It’s difficult to describe Sea State without sliding into gushing cliches or using now-overworn terms like ‘masculinity’ or ‘female desire’. An intensely original book, it begins with Lasley’s vague plan to write a book about offshore oil rigs but quickly veers into an account of her obsession with a married oil rig worker. Their brief affair, and the process of Lasley upending her life to pursue it, is laid out in excruciating, generous detail, and interspersed with snatches of interviews with oil rig workers, and reporting on the oil fields.

An Alphabet for Gourmets by MFK Fisher

In a 2013 review, Gary Indiana praised the singularity of the legendary food writer MFK Fisher: “Much of Fisher’s best writings describes periods of economic depression and wartime rationing; this gives them an emotional texture and sociological resonance largely absent from contemporary food writing, which is all but exclusively pitched to well-off consumers of luxury goods whose inner lives are presumed to be a centimetre deep, their pockets bottomless.”

The past few years have seen contemporary food writing change, at least a little, with writers like Jonathan Nunn, Ruby Tandoh and Alicia Kennedy using a political lens to produce some of the liveliest, sharpest cultural criticism happening in any field. It feels like a fitting landscape for Daunt’s beautiful reissue of MFK Fisher’s 1949 classic An Alphabet for Gourmets, which collects 26 essays under the letters of the alphabet; B is for bachelors, G, naturally, for gluttony.

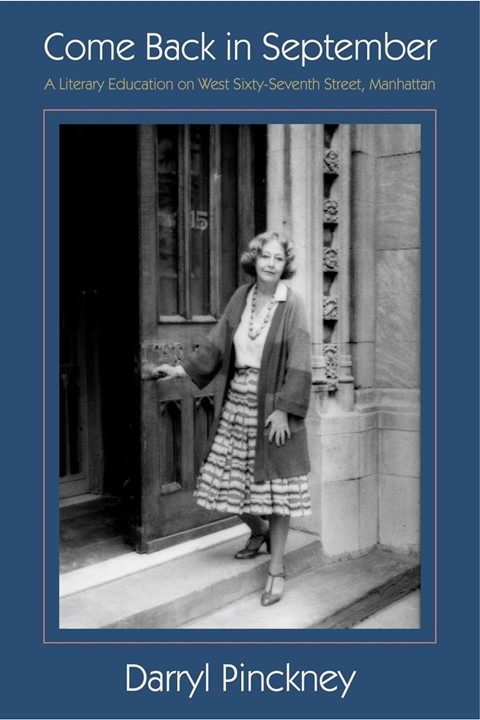

Come Back in September by Darryl Pinckney

I bought Darryl Pinckney’s memoir on a whim after Jamaica Kincaid shared it with a glowing review on her Instagram, and I bumped it to the top of my reading pile when it arrived. Come Back in September is billed as a candid account of Pinckney’s time as a kind of mentee of Elizabeth Hardwick and Barbara Epstein, in the beginnings of an East Village scene with the likes of Susan Sontag, Nan Goldin and Jean-Michel Basquiat. The book is at its best on Pinckney’s own life and family, with observations like, “In the early eighties, my father started to lose his mind … My mother had to surrender her own reason in order to remain loyal to a crazy man.”