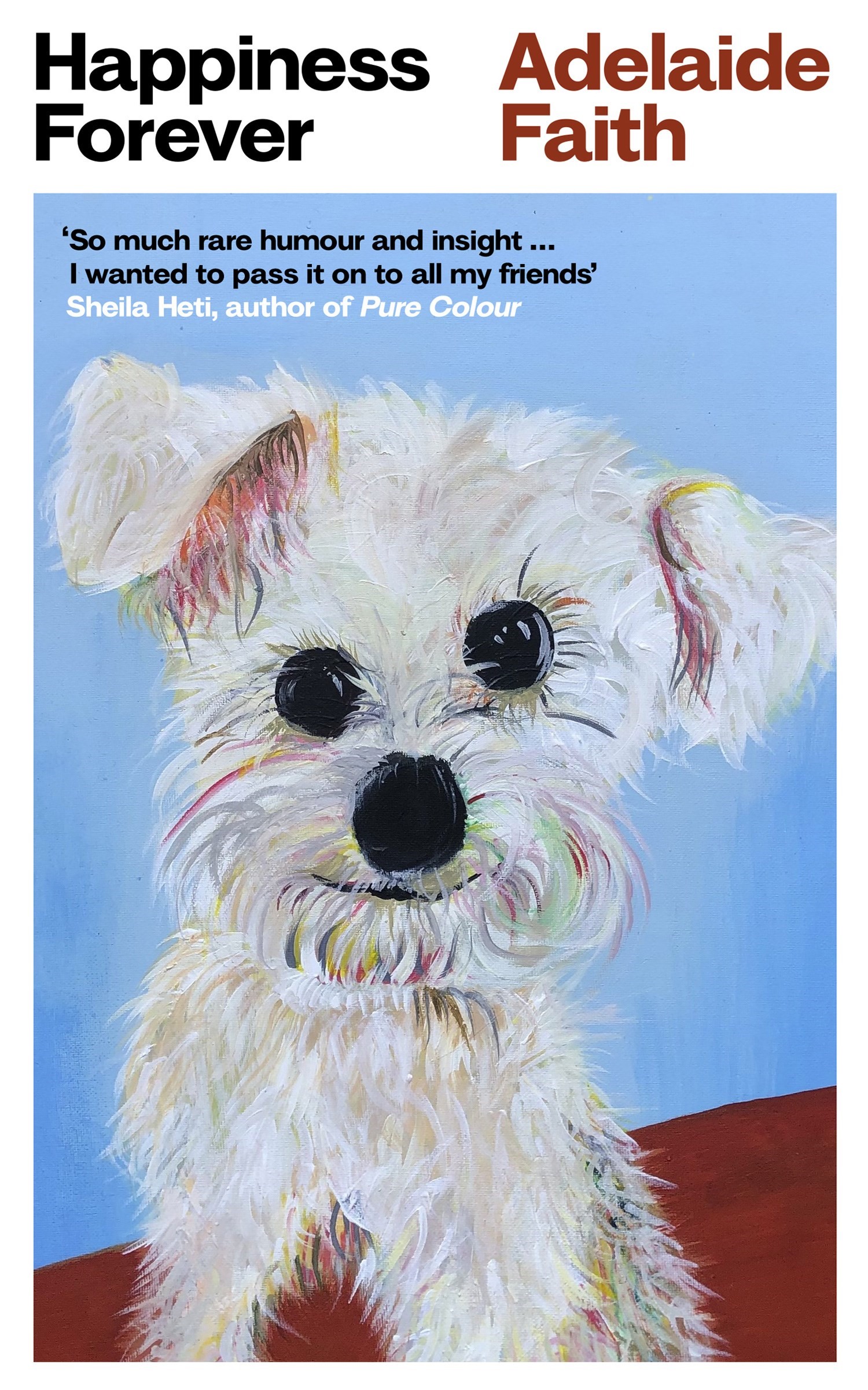

Happiness Forever, Adelaide Faith’s debut novel follows Sylvie, a veterinary nurse living with her brain-damaged dog Curtains in an English seaside town. In the wake of a toxic relationship, Sylvie becomes obsessed with her therapist, and spends most of her time – when not working or in therapy – thinking about her. The obsession becomes her organising principle. She imagines becoming a part of the therapist’s personal life, and ceaselessly tries to think of ways to get the therapist to hug her. Along the way, she meets a new friend Chloe, with whom she shares a love of books and Pierrot the sad clown.

Despite its setting, and unlike much contemporary fiction, Happiness Forever does not have what critic Parul Seghal termed a ‘trauma plot’ – rather, it shows the aftermath of trauma, the process of trying to rebuild the self and live with ourselves, day after day.

There is no ‘cure’ in Happiness Forever. Sylvie does not finish therapy; her sessions simply end because the therapist retires. The question of whether one can ever really override their own nature and leave compulsive behaviour behind is left open. But it does propose a world in which art and friendship can make life a little easier and more worthwhile.

Below, Adelaide Faith talks more about the ideas that inspired Happiness Forever.

Zsófia Paulikovics: Like Sylvie, you work as a veterinary nurse. How did you end up doing that, and how does it interact with your writing life?

Adelaide Faith: I always half wanted to be a writer, half wanted to be a vet when I was little. I used to read those James Herriot books, It Shouldn’t Happen to a Vet. My first ‘proper’ job was at Channel 4, but I got quite depressed there. It was really boring to me. I didn’t like being in an office. I think my boss could tell, and he was like, “You should take up the therapy we offer”. The therapy made me realise that I hated my life and I really wanted to be around animals, so I went to Battersea Dogs Home, where they pay you while you train. First, I worked as a kennel hand, which was really hard work physically, but still really fun. And then I trained to be a vet nurse, and I loved it.

The dog’s home also made me stop drinking, which was amazing. You couldn’t go into work with a hangover, because the whole place smelled of dog poo in the morning. When I was no longer drinking, I started making zines in the evening as part of my therapy homework, and sold them in places like Rough Trade in London. But writing long-form came much later. I’d had a child and moved to the seaside and had more time. I didn’t have the stamina to do it before.

ZP: I read that you’re in Chelsea Hodson’s writing group – how did that influence the book?

AF: Before the writing club, Chelsea had this class called Finish What You Start, which was one-to-one. It was kind of like therapy. I would do a diary of my writing and email her a report at the end of the week, because the middle stage of writing was really difficult. I hated the book. I was like, “I just feel like smoking every time I open the manuscript”. And she’d be like, “Why do you think you feel like that? Remember, this isn’t something you have to do. It’s something you’re choosing to do, and you can make it into anything you like.”

ZP: It’s interesting that the book is partly set in the therapy space, and you were doing this writing therapy all the while.

AF: It was really funny, actually, the way that class started to feel like the book. I kept trying to give the decisions about the book over to Chelsea, like I had tried to give decisions about my life over to my therapist. And I did think, “Oh god, I’m starting to idolise Chelsea,” by the end of it. When the class ended, it felt devastating.

“It just amazes me how much you can like one person. There’ll be 1,000 people that do nothing for you, and then you’ll see this one person and they make the whole human race seem worthwhile” – Adelaide Faith

ZP: Psychoanalysis is so in the culture at the moment. It feels like we’re having a bit of a therapy boom, and I wondered if that was what interested you, or just the idea of transference specifically.

AF: No, it was the opposite. I remember thinking, no one’s going to want to read this. I didn’t think we were having a therapy boom, I thought we were over that and that therapy was, you know, for people that don’t have proper problems. But I wanted to set the novel mainly in one room – I wanted it to be really claustrophobic. And I wanted a character to tell someone they were obsessed with them, and that person to have to stay and deal with it. And the power dynamics couldn’t turn unhealthy with a therapist. I just love the way therapists constantly have to treat you like you're a feasible person.

ZP: I liked how funny that made the setting, because you keep waiting for someone to break the boundary. I read it almost like a thriller.

AF: I read a lot about transference and the actualisation of the fantasy when I was in therapy, and it’s so interesting. There was this woman who sounded so distressed, she was like, “I’m straight and I’m obsessed with my female therapist.” There’s a really bad TV series I watched about a therapist who was completely nuts and just kept crossing the boundary. It was so exciting. I remember telling my therapist to watch it. But it’s dreadful – I can see that it would be dreadful [to act on it] because all the work would be lost.

ZP: I was really interested in how you showed the mechanics of obsession, and how it becomes a comfort thing, a good way to get through the day.

AF: My obsessions started when I was a teenager, with Nick Cave. I’d let myself watch one video of him, and then I’d do homework, and then I’d watch another video and do homework. It was like a drug to counteract boredom. I’d write his name in my dictionary and get such a thrill. It just amazes me how much you can like one person. There’ll be 1,000 people that do nothing for you, and then you’ll see this one person and they make the whole human race seem worthwhile.

Since writing the book, I’ve wondered if writing has cured me of being obsessed with people. Because therapy didn’t cure me of it. I still do it, but more mildly and tactically. I choose more than one person, so if one obsession upsets me, I can just think about the other one.

“Obsession is not a giving thing to do. I wouldn’t want someone to do it to me. I’m aware that when I’m obsessed with someone, I’m doing it for me” – Adelaide Faith

ZP: Pierrot is a big part of the book – what is his significance to you?

AF: I’ve always really loved clowns, circuses and fairgrounds. I did really boring, middle-class things as a kid, and I like how lawless and blended family-like circuses are. When I was writing this book, I did read up about Pierrot, and people said, “He’s a blank canvas because he’s all dressed in white and he never speaks”. I thought maybe that’s a bit like what a therapist is. But I think I like the unrequited love, that he’s always pining for somebody.

ZP: Have you ever had anyone be obsessed with you? If obsession is one of your driving forces, then someone doing it to you can be …

AF: … the worst thing ever. I’ve had experiences of it – there was this boy once who, when I would mention liking a band or something, he’d have their entire back catalogue sent to me the next day. And it was horrible. The balance feels all off. Obsession is not a giving thing to do. I wouldn’t want someone to do it to me. I’m aware that when I’m obsessed with someone, I’m doing it for me.

Happiness Forever by Adelaide Faith is published by Fourth Estate, and is out on May 8.