What Nadia Fares’ feminist film tells us about the ways patriarchal violence endangers safe passage from girlhood to womanhood

Girlhood Studies: How has visual culture shaped ideas of girlhood? In the second season of her AnOthermag.com column, Claire Marie Healy continues to investigate the on-screen girlhoods we may have overlooked.

Honey and Ashes (1996) is the story of three women in Tunisia, each striving to live on their own terms in a patriarchal society that expects them to act and behave along a set, strict path. It is a story about women, but there are, of course, men: men who control, men who abuse and, somehow worse, men who invite you in only to later reveal the aggression that is tied together with their intimacy.

But there are also women alone with other women, in communion with their sisters, with their daughters, or the memories of the girls they once were (a precept all my Girlhood Studies adhere to: that something of girlhood is always present in womanhood, because you carry it with you). The achievement of Swiss-Egyptian filmmaker Nadia Fares is to not only show how the lives of these women intersect in terms of experience, but also how the forms of patriarchal violence they endure seem to feed into one another, too. The men are in a loop of enacting violence; the women are finding a way through the tangle, for better or worse.

In Honey and Ashes, which was Fares’ first film, her subjects are respectively 20 (the rebellious student Leila), 30 (Amina, who married her liberal university professor), and 45 (Naima, a married doctor with a teenage daughter). But by showing how their respective routes to womanhood – to self-actualisation – are violently obstructed by the expectations of men, Fares is really telling a story about girlhood in this society. And as with any story of the power of women communicating with one another, it’s also a story of the power of increasing feminist education for girls – something relevant to us all, maybe especially now.

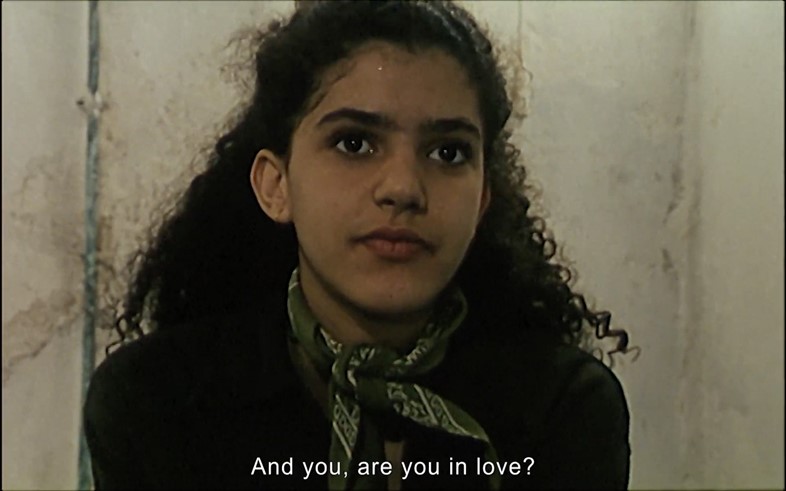

One of these moments of intergenerational coming together that is particularly screengrabbable takes place with Leila and her sisters. The sisters dance together behind the closed door of their shared bedroom (they are not wealthy); “Voulez-vous coucher avec moi?” they giggle, slinking around to the music. This is mere moments after a violent altercation with the family patriarch, who hits Leila, calling her a slut. In Fares’ telling, little sisters, or little daughters, are the innocent eyes through which disturbing events of the film are also seen and articulated. Being further from the realities of coming of age, they are both protected from the worst violence and yet always bearing witness to it.

Less explicit in its resonance, but still a moment that spoke to me, is one that takes place between Naima and her young teenage daughter, as they stop at a restaurant on the way home so that the latter can use the loo. It is, of course, located down a dark alleyway. There are a few Coca Cola crates piled up. As Mounia pees, she chats with her mother outside, before realising the door is locked. When she eventually manages to get out, they both laugh as the door handle breaks off and then drive away into even pitcher-blackness. The scene matters because I expected something really bad to happen. And it feels like more than an act of filmic suspense, on Fares’ part: with Honey and Ashes, the director is also making a point about environments that seem pre-destined for certain events to transpire. As film viewers, as so often in real life, we have been culturally trained to blame female characters for putting themselves in danger; rather than to place the fault with the male violence itself, which pollutes so many spaces.

Men enter spaces and assert control: the beach where Leila and Hassan kiss at the beginning of the film is initially idyllic, until other men come in and transform it into something dangerous and remote. Or, in reverse: the hospital where Amina’s abusive husband accompanies her, thinking he will find a male doctor to believe his version of the truth. (Instead, they are greeted by Naima as their doctor, and the space becomes safer). The brilliant opening sequence is a rebellious act against such patriarchal spaces: we see grainy footage of groups of men smoking shisha in a cafe, but Fares’ use of the voiceover of an older and younger woman giggling and whispering together subverts the masculine atmosphere. It’s almost like they’re quietly laughing at all these men.

Speaking in-conversation with writer Fariha Róisín at the FFFEST in 2019, Fares spoke about wanting to raise the voices of Muslim women, but also to build bridges between west and east through raising consciousness about other cultures with her films. The project is personal, in as far as the seed of the idea of Honey and Ashes came from her Egyptian aunt, who she would visit in Cairo throughout her own girlhood; as a girl, she saw her difficulties in finding a husband, and going through subsequent divorces, but also her rebelliousness and her courage. But as well as transmitting the stories of strong women like her aunt, and other friends in Morocco and Tunisia, Fares also emphasised to Róisín the universality of these narratives – what she calls her “puzzle” of women’s lives. These experiences are not, she emphasises, something constrained to the Middle East and North Africa. “If you analyse these three stories you can find them in Europe and you can find them in the US,” she says. “That was a very important factor, to build bridges basically.”

When Leila, at the movie’s opening, walks confidently through the square and buys cigarettes, you feel her awareness of all the eyes on her. Though the bag is slung on her shoulder, she still clutches the strap at the bottom with one hand, like I have done many times. The camera moves with her, from her perspective; or, it looks from above, like someone watching from a second-floor window. She takes off her baggy pink overcoat and headscarf, and exhales; like a Hollywood romance, she rides off with her boyfriend on a motorcycle. But the feeling of unease was, sadly, the one to be trusted – girls are not allowed to let their guard down for a minute, it seems. And it is the girl who is, somehow, blamed.

Journalist Maya Mothian-Mclean, writing powerfully on the death of Sarah Everard for the New York Times in March – the same week I wrote this column – sees a moment of reckoning in that tragedy; of threads of different kinds of violence, experienced by different women, coming together to form one overwhelming truth. “Now, perhaps, we can talk frankly about patriarchal violence”, she writes. “It’s more than physical acts of violence; it’s also the economic and psychological violence that keeps women subjugated through financial inequality, job insecurity, health inequity and the climate of fear that surrounds women as we engage in acts as simple as strolling home at dusk.” There is something terrifying, but galvanising, in the realisation that these different kinds of male violence structurally connect, and to what extent; and, though Honey and Ashes tells a story about its own, Maghrebian context, it is also a film that is striking, some 25 years on, for how it articulates what many of us, everywhere, might only be starting to say out loud.

Honey and Ashes is available to stream on Shasha Movies this month, a new independent streaming service dedicated to North African and Southwest Asian cinema. You can sign up for a subscription and support them here.