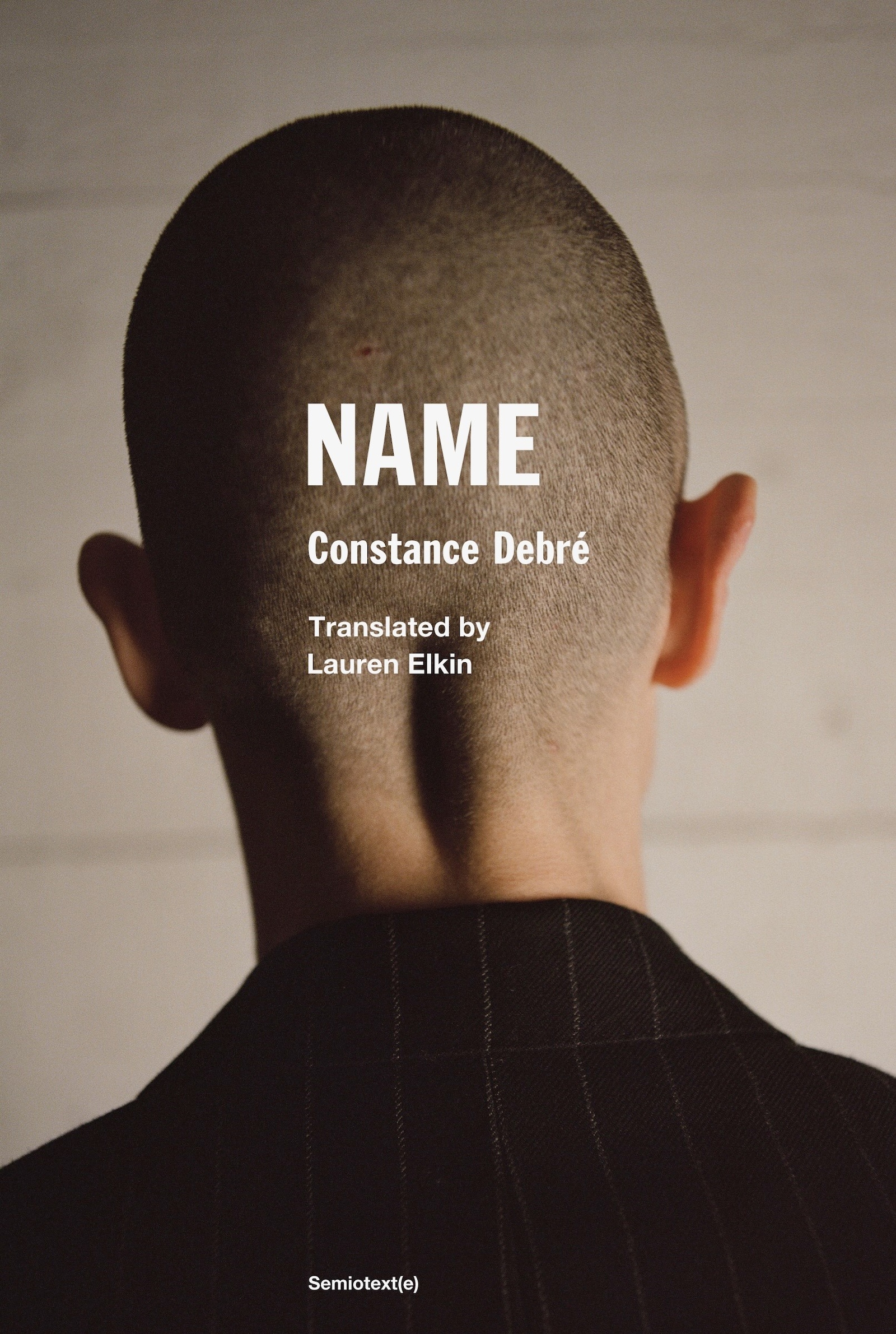

What’s in a name? Nothing at all, believes Constance Debré. The granddaughter of Michel Debré, the former prime minister of France, Constance is uniquely attuned to the baggage a surname can bear; how being from a famous family makes people think they know about you. In Name, the third book in Debré’s acclaimed autofictional trilogy, the French author takes a sledgehammer to her own family, shattering the illusion that she enjoyed a picture-perfect, bourgeois childhood in Paris. Her parents – the award-winning war journalist François Debré and aristocratic model Maylis Ybarnégaray – may have seemed glamorous and intellectual from the outside, but Debré reveals the truth: they were heroin addicts, and her mother died when Debré was just 16 years old. “You can refuse an inheritance, I’m not talking about money, it’s been a long time now since I had any, I’m talking about faith, loyalty,” writes Debré in Name. “Let’s do away with origins, I don’t hold on to the corpses.”

“When a writer is born into a family, the family is finished,” wrote the Polish Nobel laureate Czeslaw Milosz. This is certainly true of Debré, a writer who has chronicled her own life in merciless detail across three intoxicating, semi-autobiographical novels: Playboy (2018), Love Me Tender (2020), and Name (2022), each of which has been translated from French into English (Name is translated by Lauren Elkin). A masterclass in voice and atmosphere, the trilogy chronicles a time of great upheaval in Debré’s life – she leaves her husband and becomes a lesbian; quits her job as a lawyer and becomes a writer; fights for custody of her eight-year-old son, who is at risk of being taken away from her thanks to her new lifestyle. These books are highly addictive, designed to be read – or inhaled – in one sitting, with short, sharp sentences that pack in elegance and brute force in equal measure. They have also been hailed as a manifesto for a simpler, more ascetic way of life; in them, Debré reads, writes, swims, smokes, has sex, sleeps, and not much else.

Speaking over the phone from Berlin, where she will be teaching literature at the Free University of Berlin for the next three months, Constance Debré talks about family, identity, the line between life and fiction, and her thoughts on another famous and controversial work of autofiction, Karl Ove Knausgård’s My Struggle series.

Violet Conroy: What compelled you to write Name, and think about ideas around family and inheritance?

Constance Debré: I knew I had this thing in my pocket, and by thing, I mean family, childhood. That material is always very rich. Mine was a bit special because my name in France is kind of known, so I always had this feeling. People have this image of you socially, from your name, situation, or what your parents do for work. And there’s this gap between your social image and your relationship to your social image. Because of my public name, I had the feeling this was something interesting to dig into. And also, I have always been really struck by the fact that people believe in those things, like identity. I wanted to use this material I had – every writer needs material, and very often we use our own – but also to twist it. It’s a novel, so of course it’s not only about ideas, it’s about movement, emotions. It’s not at all a manifesto, as some people have presented it. It’s a novel. A novel is not a manifesto.

VC: Has becoming a writer helped you forge a new identity outside your family name?

CD: No. I don’t believe in identity, I’m not interested in who I am at all. I don’t think it has any meaning to anyone. It’s a lie, it’s a trap. I’m no one. I’m a body and what I’m interested in is what I do, like work. We’re just bodies in the middle of birth and death, in a place, and that’s about it. There’s no answer.

Sometimes I felt like the image [people had] of my family was kind of funny. I’ve read that people picture me as some kind of Kennedy. That’s so funny [to me]. People, especially in the lawyer milieu, knew my name. It was funny because [their assumptions] were not my memories. For instance, when they talk about privilege, of course I had some privilege because I grew up in an educated milieu, but we never had money. My parents were drug addicts, and my mother died when I was young. I couldn’t be like my parents, because they were drug addicts – intellectuals, but drug addicts. I had to find my way.

What matters is what you do. I feel that I’m doing the right thing when I write a sentence that captures some truth. Not a truth for me, but some kind of truth that works for anyone. This is, to me, what literature is about. It’s about writing from your very personal experience, and it works with everyone who, by definition, has a very different story. That’s why we can read authors who died 500 years ago. Even when I read certain passages of Homer, I know this feeling.

“The way I write, with some kind of distance, is supposed to make the readers feel something … I’m against any kind of sentimentality” – Constance Debré

VC: In Name, you write about painful childhood memories in a very unsentimental, almost brutal way. What kind of emotional landscape are you trying to create in your books?

CD: Thank you for asking me that question, because sometimes I feel like there’s a misunderstanding. I never pretend that in real life, nor in my books, that I don’t feel anything. Not at all. It’s just the way I write. I’m not the first one to try to do that, to show and not to tell.

The way I write, with some kind of distance, is supposed to make the readers feel something. You think and you feel at the same time, it’s a mix of things. But the feelings I want the readers to have are not necessarily the feelings I might have about the things I’m writing about. I just want something to happen to the readers. I think it’s kind of obvious that I have feelings in the way I tell stories, but I’m not going to write, ‘Oh, I am so sad. I cry.’ No, I can’t do that. It’s about personal taste – I’m against any kind of sentimentality. I hate it. I don’t think it’s beautiful.

When you talk about feelings, suddenly it’s all too much. I prefer not to spoil them with words. I prefer to make people feel the feelings, instead of telling them. When people show off their emotions, I don’t believe in them anymore. I think it’s more beautiful to keep quiet about those things.

VC: Semiotext(e) says that “Name approaches the heart of the radical emptiness that your earlier books were pursuing”. Can you talk about your choice to strip back your lifestyle and relinquish worldly possessions?

CD: I’m not saying I live like a complete monk. But we know that we’re overwhelmed with things and live in a very material world. Maybe we shouldn’t participate as much. Not only is it absolutely disgusting, but when you are in this material world, you have no freedom. That’s why this notion of emptiness is not only a material thing, but it’s also a way of thinking. Same with origins, childhood, names or identities. If you believe, for instance, that you are only the result of your childhood, there’s no space for freedom, which means creativity and responsibility. Emptiness is something to be filled. And that’s why life is interesting, because we are a body, and we can do lots of things. But we have to see ourselves as something blank. This concept of emptiness is not new – it’s all over ancient Greek philosophy. Every philosophy is about trying something new, and to try something new, you have to cut.

VC: I’m interested that you called Name a novel earlier, since it’s marketed as autofiction. Do you feel any kinship with that term?

CD: To me, autofiction is fiction, so it’s a novel. The word autofiction is so ugly. And I don’t really care about labels, as long as it’s clear that it’s fiction. Of course, I use material from my life, but this is not the way I would talk to a friend in a cafe about my life. I create a character, I create style. To me, a novel is all about form, and the form is the way a narrator or characters go through a story. In a way, I’m more interested in style that the material I’m using. I’m trying to make it absolutely clear through my style that it’s a novel. And if it’s not clear, then literature is not clear. Literature is not a pure thing, like life. That’s why I love it.

VC: I’ve recently read Karl Ove Knausgård’s My Struggle: Book One [a famous example of contemporary autofiction]. Do you have an opinion on those books?

CD: I read lots of the My Struggle books, and I still don’t know if they’re good or not. And I love that, because this guy is good, he managed to keep me reading. The books are not that good, they’re boring, his life is boring, and he has no real style … But still, I was reading it, so it was good! He’s trapped the reader. I cannot completely side with the people who say this is the most interesting book ever written. But he’s probably smarter than me in some way … He got me.

“If you believe, for instance, that you are only the result of your childhood, there’s no space for freedom, which means creativity and responsibility” – Constance Debré

VC: I often wonder if people think his books are good only because people are fascinated by ‘real-life’ stories, which links back to the recurring discussion around the death of the novel.

CD: I mean, it’s not completely new. There have been lots of books in the first person before, like The Confessions of Saint Augustine, which is absolutely beautiful. There’s also Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Proust. I think there are many different things underneath this first-person thing. Maybe some readers believe reading books about other people’s lives can serve as a model for their own lives. Of course, a novel is always some kind of model for our lives.

There are good and bad things about the first person. Sometimes I can’t stand it anymore, when it’s very plain. But sometimes it’s interesting, because classical third-person books can be extremely old-fashioned and boring, too. There’s no one way to write a good contemporary novel. But yes, some readers are fooled by the fact that it’s a real person talking. But a book is never real life – that’s what fiction is.

Name by Constance Debré, translated by Lauren Elkin, is published by Semiotext(e), and is out now.