Daisy Woodward meets Jocelyn DeBoer and Dawn Luebbe, the duo behind Greener Grass, a surreal soccer-mom satire and one of this year’s most weird and wonderful cinematic offerings

Of all this year’s film releases, you’d be hard pressed to find a more weird and wonderful offering than Greener Grass, a suburban soccer-mom satire from writing/directing/acting duo Jocelyn DeBoer and Dawn Luebbe. “We wanted our viewers to bask in normalness and then to hit them with something really unusual that they don’t expect,” DeBoer tells AnOther over the phone – which is exactly what they achieve in this dark comedy, with its pin-sharp commentary on society’s reigning obsession with outward appearances and our quest for others’ approval.

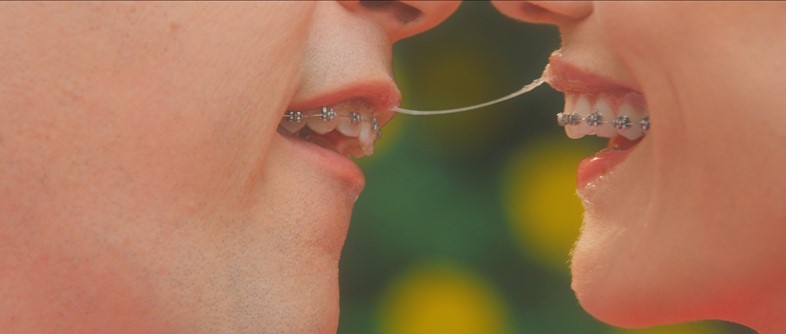

The film takes place in a picture-perfect town where everything comes in a saturated shade of pastel, reminiscent of Tim Burton’s Edward Scissorhands. Every inhabitant sports braces (a telling metaphor for the painful, collective quest for self-improvement), colour coordinates with their spouse, drives a golf buggy and slurps bubble tea. Tightly gritted smiles and excessive politeness barely mask the community’s raison d'être: to get one up on their neighbours. Our protagonists are housewives Jill and Lisa (played by DeBoer and Luebbe), the former petite, skittish and desperately eager-to-please, the latter tall, sardonic and bitterly jealous. We meet them sitting in the bleachers of their young sons’ soccer game, discussing the recent murder of a yoga teacher.

So far, so Stepford. But when, after just a few short minutes, Lisa compliments Jill’s new daughter, Madison, things take a surreal turn: Jill impulsively offers up her baby to her frenemy, who merrily accepts. From there, things go from bad to worse for the fragile Jill who comes to regret her decision with increasing despair, rendering her the only character (with the exception of the yoga teacher’s crazed killer) to let slip the neighbourhood’s “righter-than-rain” facade.

Many memorable moments ensue, from the laugh-out-loud to the downright baffling – if you’re a fan of Todd Solondz and John Waters, then this is the film for you. Some choice highlights include: Jill’s husband Nick’s addiction to his new, specially filtered pool water, which he consumes with reckless abandon; a children’s TV series called Kids With Knives, which sends Lisa’s son into a dark downward spiral; and the time Jill’s son delivers the ultimate unlikely put-down. “You’re a school,” he shouts, to Jill’s horror and dismay. “‘I am mom. I’m full of classrooms. So many clocks in me!’”

DeBoer and Luebbe first met at Upright Citizens Brigade theatre in New York, an improvisation and sketch troupe founded by Amy Poehler. “I was immediately drawn to Dawn’s sense of humour,” says DeBoer of their creative chemistry. “We both came from the suburbs in midwest America and, during pitches, I loved how Dawn played with drama in the mundane and exploring domesticity in a heightened fashion.”

These were themes the pair revisited when, after four years, they both opted to leave New York for Los Angeles and decided to work together again. The result was the first iteration of Greener Grass – a short film centred around the same characters. “We wanted to explore politeness taken to the extreme: the lengths we go to make the people around us happy and comfortable, while sacrificing what we actually want,” says DeBoer, as an image of the film’s characters guzzling their food straight from a restaurant floor after an accidental spillage, springs to mind. “We drew a lot from the mannerisms that we observed in other people, growing up in the midwest,” Luebbe expands with a chuckle. “Albeit pushing it to weirder heights.”

The Greener Grass short met an award-winning reception, spurring DeBoer and Luebbe to evolve it into its newly released, feature-length format. As with all the best movies, a large part of the film’s appeal lies in the idiosyncratic world it occupies, enhanced by sickly sweet cinematography from Lowell A. Meyer and a synthy, sci-fi soundtrack. The writers spent hours fleshing out the Greener Grass universe in all its visual and symbolic splendour. “We looked at a lot of photography, in particular Gregory Crewsdon’s formalist set-ups that showed these dramatic light sources among the inherent darkness of suburbia,” says Luebbe of the film’s unsettling take on a 1950s, white-picket-fence aesthetic. “We also looked at Bruce Davidson, William Eggleston and Stephen Shore, these other 20th-century photographers who highlighted suburban American landscapes in a dark and often humorous light.”

When it came to the dialogue, DeBoer compares the writing process to the childhood games she played with her two sisters in her family’s backyard. “When I work with Dawn, I get the same creative high,” she laughs. “We always write together, sitting next to each other, with one of us typing,” Luebbe adds. “We spitball back and forth. Perhaps because of our improv background, our strongest writing always happens when we’re building on top of what the other one just pitched, refining the joke and taking it even further.” Their approach to directing is similarly collaborative. “We do everything together,” says DeBoer, “the only difference is that Dawn obsesses over the composition, while I obsess over the performances, which is a good balance”.

And what do the diligent duo hope that viewers will take away from this admirably absurd offering? “What was most important to us was to take people on a cinematic journey that they had never been on before,” DeBoer says with an audible grin. “Dawn and I are really drawn to surrealist films that have a formalist aesthetic, but sometimes these lack an emotional component. We wanted to make a surreal film that people felt invested in.” And with Greener Grass – with its abundance of quirky characters and inherent oddities – there’s no doubt they have done just that.

Greener Grass is in cinemas, and on digital streaming platforms, from today.