At the tender age of ten Bruce Davidson embarked on a quiet, solitary hunt in search of the perfect photograph. It was a journey that began when his mother built a darkroom in the basement of their home in Oak Park, Illinois so that he could meticulously print and edit his work, scanning contact sheets in search of gems preserved in slips of silver gelatin first captured on his forays out into the world.

“I always felt like an explorer on some faraway planet,” Davidson tells AnOther from his home in New York City. “I work best if I’m left alone. I like to explore, uncover, observe and reflect without anyone looking over my shoulder.”

His independence has been an integral part of his career, a trait that announced itself while serving in the US Army during the 1950s. Posted to the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers in Europe outside Paris, Davidson was given enough freedom to follow his own path – one that lead to his meeting the widow of the impressionist painter Leon Fauché in Montmartre, who he photographed alongside her late husband’s paintings. His photographs of their encounter, first published in Esquire in 1958 in an essay titled Widow of Montmartre, caught the eye of Henri Cartier-Bresson, who arranged to have Davidson inducted into Magnum Photos that year. As a member of the fabled photo agency, Davidson has become one of the most influential photographers of our time, writing history with his camera in a series of landmark images.

Now 85, Davidson takes us deep inside his decades-long body of work in the new exhibition Subject: Contact at Howard Greenberg, New York. Here, we see 1950s and 60s America through Davidson’s eyes as the country entered the modern age.

Revisiting the series Circus, Brooklyn Gang, Time of Change, and East 100th Street, Davidson pairs his most powerful images from each alongside the contact sheets from which they were drawn. The result is a revelation as to the way the photographer works: a deliberate, meditative stillness that allows him to observe and absorb before he acts.

“I look at my contact sheets like musical notes on a score – it’s the way I saw something, how long I saw it, whether I overlooked it or whether it was meaningful,” he says.

The act of looking has guided Davidson through different worlds, allowing him to engage as silent observer, wordlessly channeling the depths of the human condition into a single frame. The series featured in the exhibition reflect mid-century America: disappearing cultures, alienated youth, the fight for Civil Rights in the South, and impact of systemic racism on the people of New York City.

Recognising the power of the photograph to inform, shape, and change the way we see and think, Davidson’s strength lies in his ability to attune himself to the moment without disrupting it, in order to bear witness to an intense truth about life as it reveals itself.

Looking at the contact sheets, one might imagine Davidson moving like an animal on the hunt, lithely taking position with precision and poise, patiently awaiting the moment to noiselessly strike. “I work quietly and quickly but also stand back to observe what’s in front of me. The main thing is to be open and honest and not intrude or make false judgments,” he says.

As an outsider looking in, Davidson occupies a curious space, that of a guest in someone else’s home. His photographs are windows into worlds we might not otherwise know or dare to go into ourselves. A humanist at heart, Davidson does not consider himself a documentary photographer merely recording events as they unfold, but rather a participant having an encounter with the invisible.

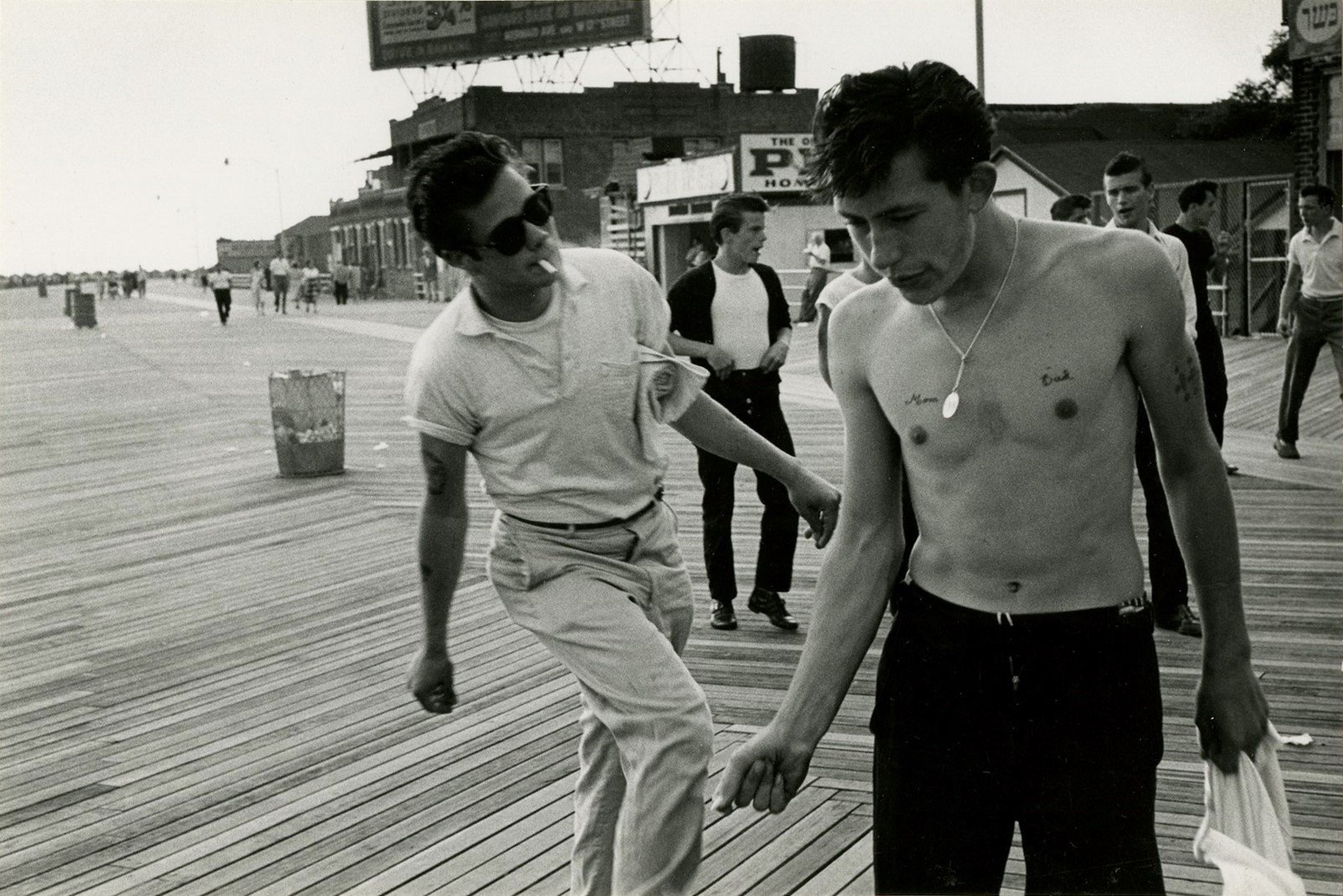

It’s a sensibility which manifests beautifully in Brooklyn Gang, a series that Davidson made following the Jokers through the streets of South Brooklyn in 1958. Here was the real “rebel without a cause”, white teens who had been disavowed by society, abandoned and abused, falling through the cracks like so much sand on the Coney Island boardwalk.

“They trusted me to observe their depression and isolation without judgement,” Davidson says. “There was nothing for them in the community so they had to bond together and gave me entrance to their dysfunctional world.”

Davidson’s photographs, first published in Esquire in 1959 accompanied by a text by Norman Mailer, were gentle and tender, filled with a yearning and a subtle sense of romance for the close-knit group born out of vulnerability. It made for a knowing contrast when placed beside the media’s sensationalistic portrayal of juvenile delinquency that was all the rage at the time.

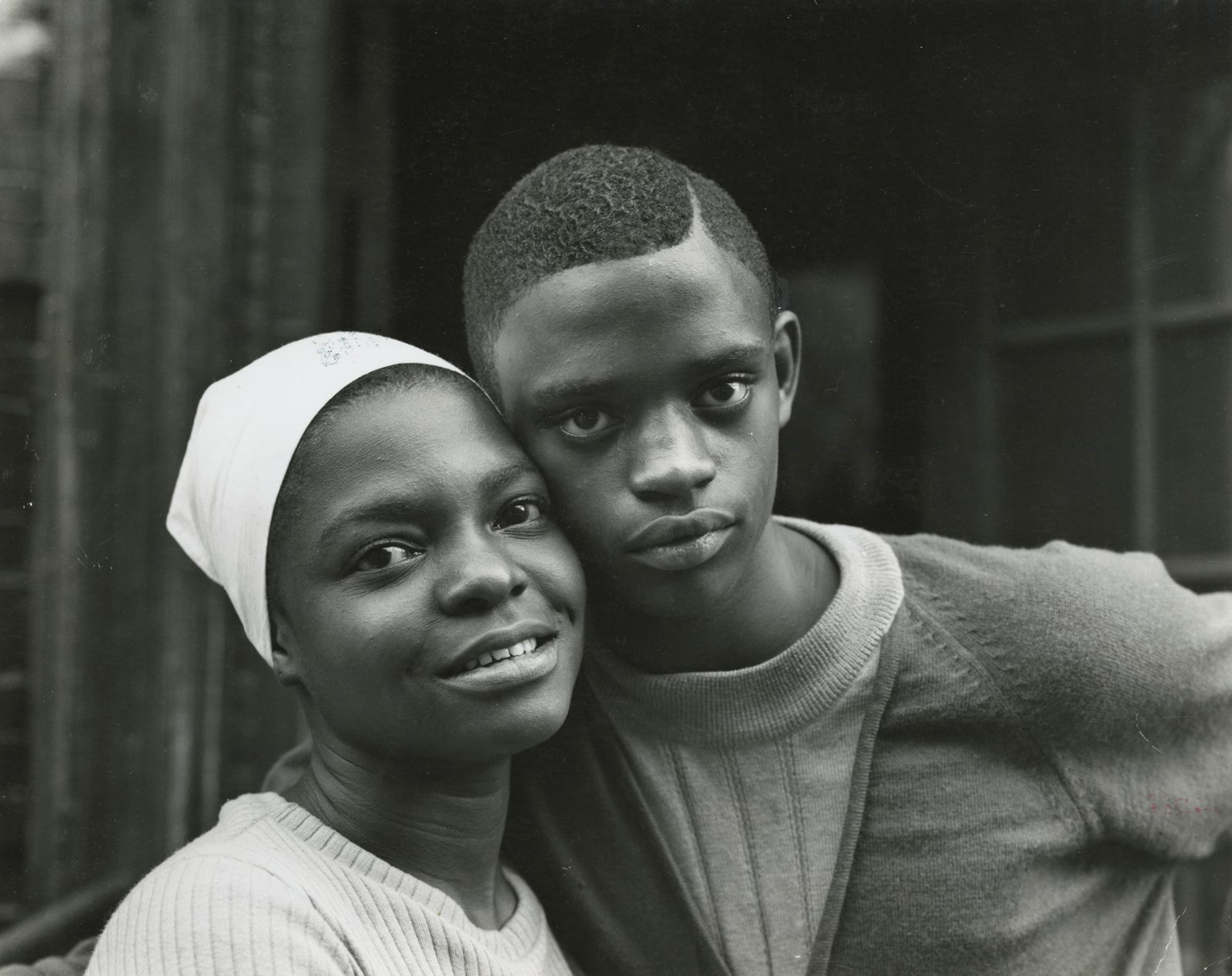

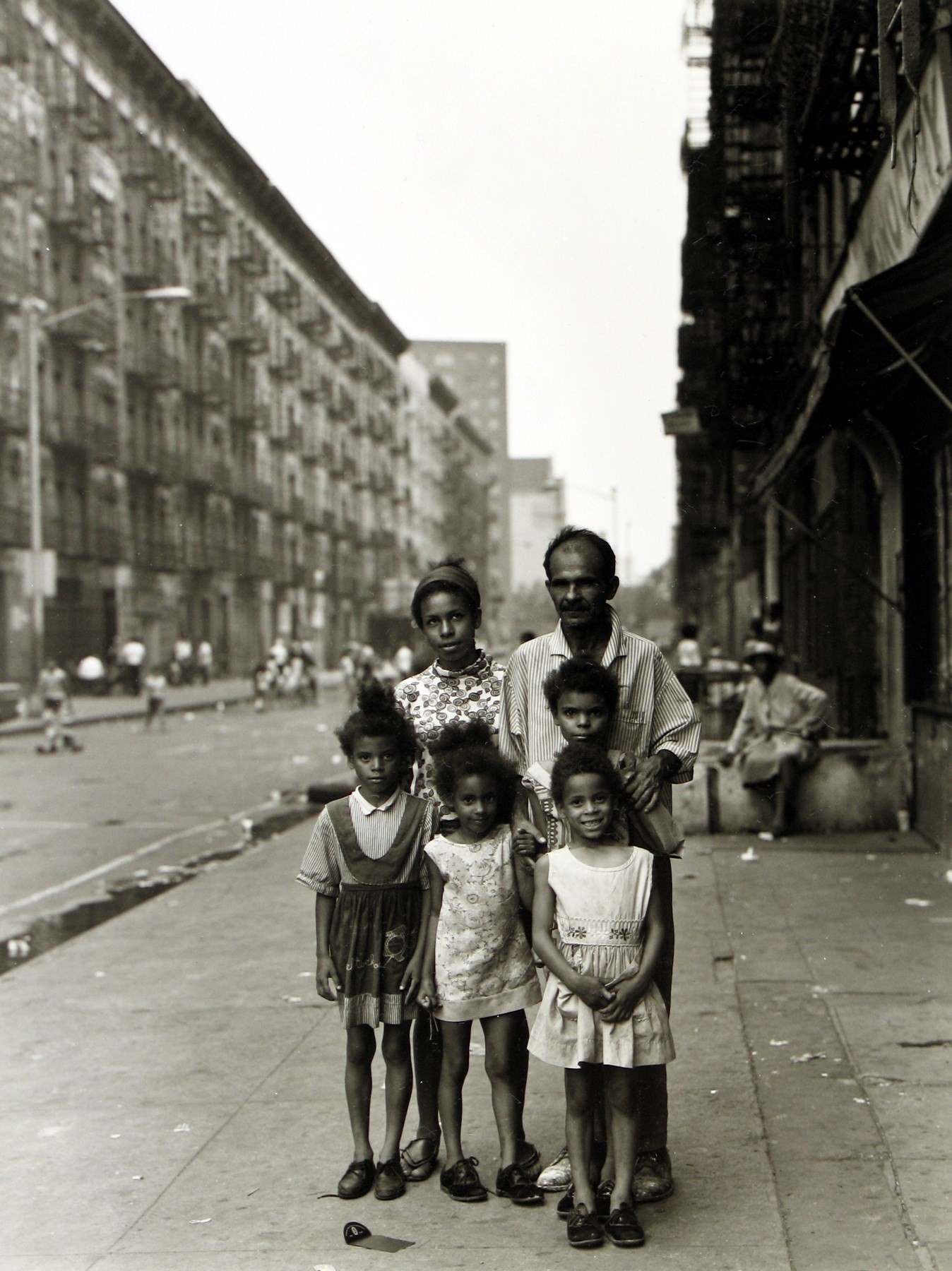

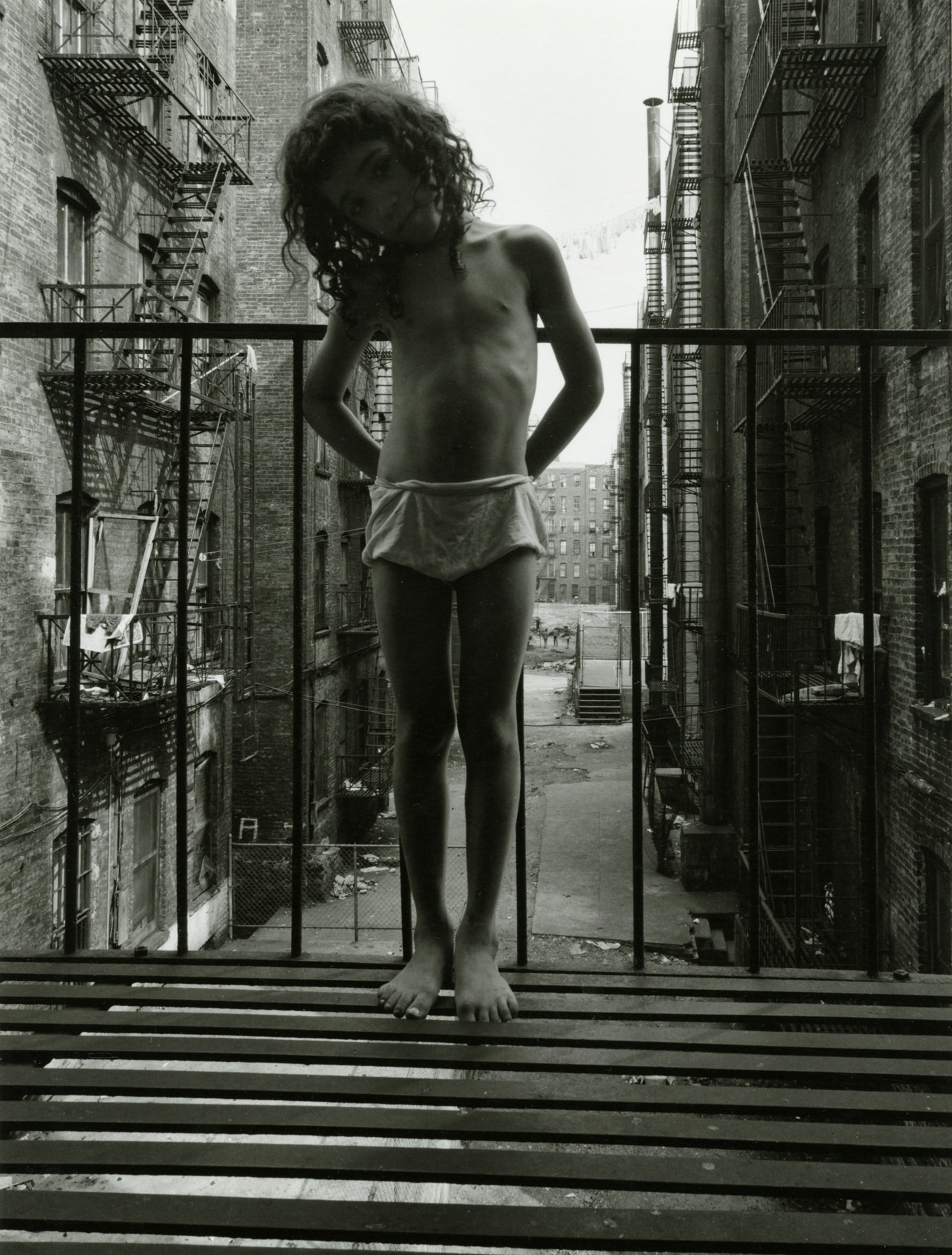

Though Davidson’s politics are not overt, they make themselves known by his choice of subject and the empathy he extends to them – revealing the power of visibility and representation in what is otherwise a closed system. Davidson considers East 100th Street his most sacred work, which stands as a telling counterpoint to the Brooklyn Gang series.

Here, in East Harlem, was the outcome of systemic oppression: de facto segregation, redlining, unemployment, substandard housing, and underfunded public schools conspired to create a permanent underclass along the lines of race. Known as the “picture man,” Davidson chose to use a 4 x 5 view camera with a tripod and black cloth to create environmental portraits of people living in conditions of extreme urban poverty on one Manhattan block between 1966 and 1968.

“I felt that by documenting them it was giving the community a human face and voice. This later became a calling card to the mayor and other city officials for urban renewal in that area,” Davidson says. “I was curious and thought I could impart some positive knowledge through my work to make a change.”

Bruce Davidson, Subject: Contact is at Howard Greenberg in New York until June 15, 2019.