"And what do you benefit if you gain the whole world but lose your own soul?" In the contemporary art lexicon, most would seem to like to ask this question of the multi-millionaire Zeng Fanzhi, an artist whose career began in 80s China...

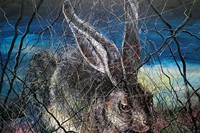

"And what do you benefit if you gain the whole world but lose your own soul?" In the contemporary art lexicon, most would seem to like to ask this question of the multi-millionaire Zeng Fanzhi, an artist whose career began in China in the 1980s with unsettling and often politically charged paintings. In Britain, we have a tendency to distrust any artist who has had a lucrative career (we are, after all, the founders of the build-them-up-to-knock-them-down school), and after a certain point editors and journalists tend to prefer to discuss an artist's material wealth and lifestyle, rather than their creative output. However, it would be grossly unfair to take such a tawdry view of Zeng, whose current exhibition at Gagosian Britannia Street – his first on these shores – deals with mortality, sacrifice and reflection, proving beyond a doubt that he is not an artist in danger of selling his soul. Taking as its source material the story of Albrecht Dürer's brother sacrificing his own artistic ambitions to allow Albrecht to go to school and learn to paint (the hard physical toil he undertook causing him to suffer arthritis in his hands), the show exhibits huge, fascinatingly detailed homages to Dürer – hands locked in prayer, an old man in deep contemplative meditation – and endlessly complex spider-like scenes of dense woodland, through which distant glimmers of light shine. AnOther took some time to talk to the strikingly composed, modest and self-effacing artist to find out why, despite his well-documented wealth, it is a simple, Buddhist-like spiritual communication he seeks to have with the world through his art production.

What concerns have carried through your career – what has remained the same and what is fundamentally different now?

I think what remains unchanged is my pursuit of beauty.

What is your definition of beauty?

I think everyone has their own definition of beauty, but as far as I’m concerned beauty means staying true to what touches you, whatever moves you and whatever brings up your feelings and emotions – this is my definition of beauty. Also, beauty is not just about being beautiful, it is about being everlasting. I experience a forward mobility of my inner mind and my inner state while I’m making these paintings.

There is an intense complexity of line in these works, are you fascinated by the minutiae of the world?

I am always very fascinated by delicate and micro-aspects of the world, and usually when I discover the beauty of these aspects I will amplify and multiply the effects of what I see into the paintings. This is why I make such huge paintings. I want to exaggerate and underscore the beauty of these delicacies and these minor aspects. I believe that many artists are moved by the micro-aspects of the world and this is what inspires them.

"As far as I’m concerned, beauty means staying true to what touches you, whatever moves you and whatever brings up your feelings and emotions..."

Is there any specific thing from your youth you can remember that inspired you to paint?

I think I was influenced and inspired by many aspects but I couldn’t name a specific one. It was through a gradual process that I found myself gifted in art and painting. When I was young, life was so tough that it was difficult to think about one's future. At the time, the most important thing was whether we could make ends meet and feed ourselves. I think before my 20s the most important thing to me was whether I could feed myself. Now, living in such a comfortable environment, I can, of course, discuss art, but it is still very difficult to do so – it is very difficult for me to talk about art. I’m better at communication with people and the world with my artwork than I am with language.

The lines in these works make me think of the lines on the palm, do you believe in predestination?

I believe more and more in the notion of fate and how what we call chance plays a role in that. I have begun to believe that there is a predestined life for everyone, and sometimes I feel like it is by fate that I was guided in a certain direction, instead of me choosing one direction initially and of my own volition. I believe that sometimes even though I make a plan there may be other changes that will overtake the plan completely – sometimes a very minor aspect can change the whole plan.

What is the most important thing for you in terms of your legacy? Do you think in terms of leaving a legacy as an artist?

Admittedly, all artists want their work to be immortal and everlasting, and I hope that my work can be appreciated when I’m deceased. I hope that when people look at my work they can find something new, and they can find something they wanted to see within the paintings; the things they are looking for. However, I think in terms of the word legacy, I would say it is important to leave a spiritual legacy to the world instead of a materialistic one.

How has fame affected you, and have the projections of 'the most important artist in the world' and so on made it more difficult to create art?

No. I am secluded from the world when I go to my workshop in Bejing, and as soon as I close the door and am in the workshop on my own, I feel secluded and am able to focus on my creation. If you ever come to Bejing and my workshop and have a chance to see how my life is lived, you will notice such a situation.

Zeng Fanzhi is at Gagosian, Britannia Street, until January 19 2013.

Text by John-Paul Pryor