As a new exhibition chronicling the revered fashion photographer's early oeuvre opens in New York, we examine the deathly quality of her most seminal works

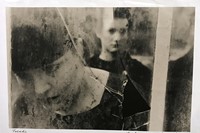

A Deborah Turbeville photograph is plunged in decay. Its gelatin edges are corroded by the spectre of compromised expectations and its fields are oppressively grey. From her first editorial for Vogue, which featured Geoffrey Beene-clad models shot outside a bleak Manhattan cement factory, Turbeville’s images were stark, melancholy affairs of minimalist couture sceptical of the industry's prevailing aesthetic of sunny girls in swirling frocks. In a Turbeville picture, women idle in a twilit fugue state; clothes seem entirely beside the point.

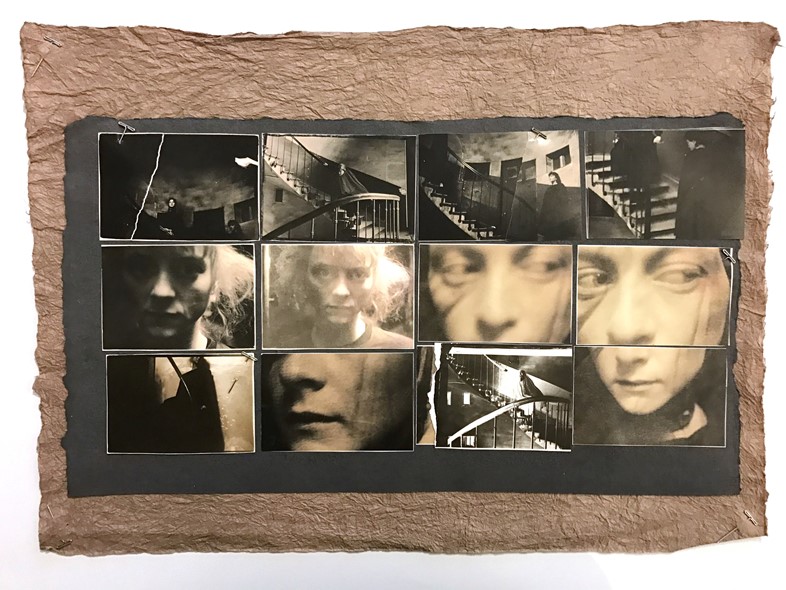

The period between 1974 and 1982 is the focus of a new exhibition of prints and photo collages at Deborah Bell Photographs in New York, many of which are unpublished alternates of commercial work produced for Comme des Garçons and Charles Jourdan. During this time, Turbeville made some of her most resonant work, and developed signatures which continue to colour the industry.

Represented in the exhibition is There’s More to a Bathing Suit than Meets the Eye, the 1975 swimsuit spread for American Vogue now colloquially known as simply The Bathhouse Series, in which gaunt, glass-eyed models are arranged in an abandoned New York bathhouse. The series is cited among the premier examples of fashion photography, but their immediate reception was less gracious. The writer Nancy Hall-Duncan recalled critics who saw the shots as “evoking the grisly aura of a concentration camp or the frightening vacuousness of a drugged stupor”.

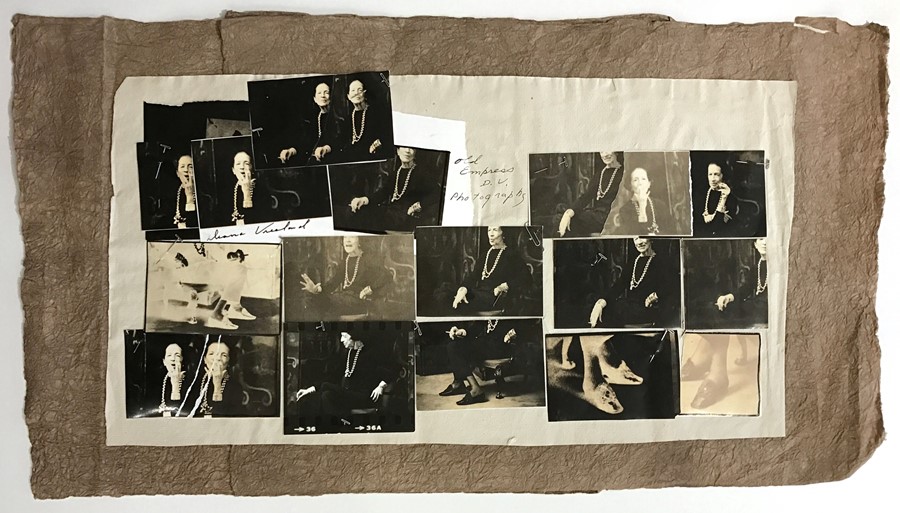

Additionally featured in the show are her Diana Vreeland studies; The Last Empress, a collage of test shots which capture the mythic editor’s imperious humor; the series Woman in the Woods for Italian Vogue; and l’Heure entre Chien et Loup, where Turbeville’s phantasmic subjects appear removed from time entirely. They do not so much obsess over death as trail it along behind them.

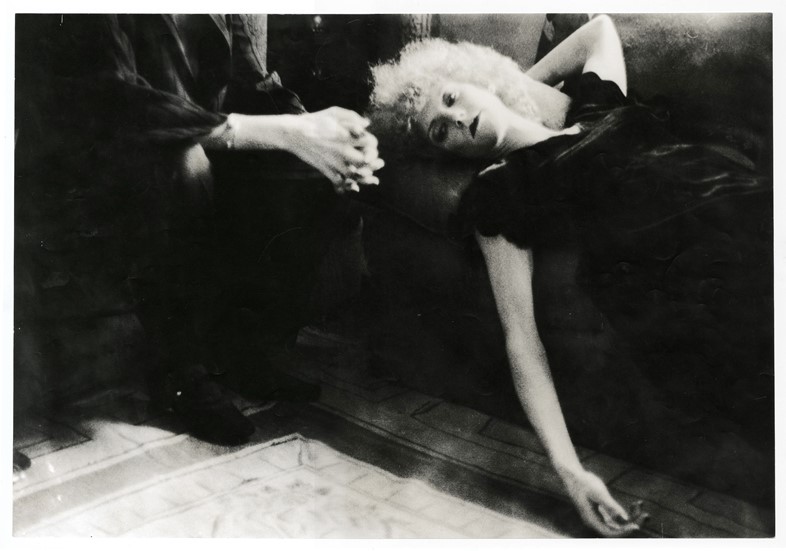

This deathly quality was at its height in Unseen Versailles, a dirge of eroded opulence and moth-chewed glamour, commissioned in 1981 by Jacqueline Onassis (Onassis had a preternatural eye for pioneering photography; she published William Eggleston’s Democratic Forest a few years later). In these, listless models slump in Louis XIV chairs in crumbling drawing rooms shrouded in sheets as though in a Magritte painting.

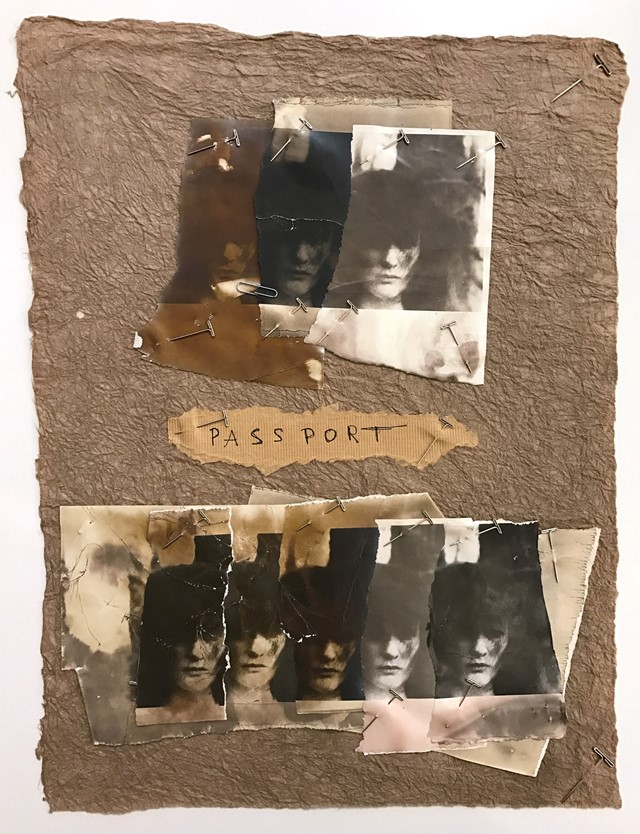

In their evocation of a disintegrated aristocracy and last gasps of the Old World, the Versailles pictures introduced an abiding theme in Turbeville’s work. She conjured the ghosts of Mariinsky dancers in St. Petersburg, circus performers in Budapest, and spectral wraiths in Normandy forests. As if to amplify this quality, Turbeville tacked her mottled collages, marked with her own handwritten captions, to kraft paper, making them not only photos but also objects, like some found relic.

Turbeville, who died in 2013, was making these pictures as the feminist movement became part of a national consciousness, with women’s fashion and photography within advertising were going through their own changes. In her upheaval of fashion’s visual tropes, she’s often tethered to Helmut Newton and Guy Bourdin; contemporaries who were making oversaturated images that seeped sex. Yet where Newton and Bourdin seized upon bare limbs, Turbeville seized time and motion entirely, heaving the vaporous ennui of an Antonioni film into single frames.

Turbeville’s women inhabit a world tinted by the psychological traumas of exisistence, diffused by a mist that declines to lift; her universe often feels like avant-garde Japanese couture as directed by Edvard Munch. As much as these pictures serve to advertise a new spring collection, their true subjects more often seem like a window into the interior lives of women.

She photographed her models intimately, yet the emotional gulf between them and the viewer at times seems insurmountable, as though seen through a scrim. What these women might be thinking as they drape themselves over dusty velvet couches, or huddle together in furs over an unlit fireplace can only be known to them, and one senses that was what Turbeville was getting at. “Glamour and beauty don’t always go hand in hand with emotional security and happiness,” she once said. “Sometimes the two go the very opposite ways. Some simple, plain woman out in Wyoming probably has a more pleasant life.”

Deborah Turbeville runs from November 16, 2016 until January 28, 2017 at Deborah Bell Photographs.