Lunch is important to Azzedine Alaïa. The designer often gathers friends, clients and his intensely loyal family of staff around the glass-topped table in his Paris atelier, for long, languorous banquets. Everyone is looked after generously, with equal love and respect. Indeed, Alaïa’s fondness for people – women in particular – and his ability to bring them together, learn from them, understand their needs and deepest desires, is woven into the very fabric of his designs. We joined him at the table.

It’s the 24th of May and so quiet in the dimly lit Galerie Azzedine Alaïa, in the heart of the Marais district of Paris, that the dropping of pins might be heard. The space, presided over by the designer himself, and curated with the help of collaborators and friends, is currently home to an exhibition of the work of the great French author and artist Pierre Guyotat. For those unfamiliar with Guyotat, who is a veritable institution in France, his writing throughout the latter part of the 20th century tirelessly challenged that country’s status quo: enforced militarism, and literary censorship in particular. Such is his status that his most famous novel, Éden, Éden, Éden, published in 1970, boasts forewords by the philosophers Roland Barthes and Michel Foucault.

Guyotat’s manuscripts, predominantly lent to the gallery by the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, form the backbone of the narrative. His early work is on paper: words typed, crossed through then over-written by hand. Later come iPads plugged into walls – Guyotat’s preferred manner of expressing himself today. Alongside these and Guyotat’s own drawings and photographs are pieces by other artists reacting to his oeuvre. Among them are Christoph von Weyhe; Daniel Buren; Klaus Rinke; Juliette Blightman; Cerith Wyn Evans; Elijah Burgher; Paul McCarthy; Michael Dean… The latter found an English copy of Éden, Éden, Éden sodden with rain outside a bookshop in the North of England when he was just 14 years old. So much did it inspire him to forge his own path that this very object, its pages fragile and curled, desiccated like a pressed flower, takes pride of place in the exhibition.

“Pierre Guyotat: La matière de nos oeuvres” is among the most important shows to have been staged here to date. In the accompanying catalogue, M Alaïa’s preface, written in French, translates thus: “I have great admiration for Pierre Guyotat. Through his language, he has elevated the French language. He is capable of speaking about things that aren’t spoken of and of giving those things great beauty. His language is both powerful and subtle. It is unlike anything else.”

Although Azzedine Alaïa is too modest a character to say it, he has also, in his own way, elevated language – that language in his case being the language of fashion. And his immediately identifiable clothes, though much copied, remain unlike anything else. He has been refining his chosen métier for more than half a century and is now universally respected – even revered – both by the women who love to wear his designs and by others of his profession, which, it goes without saying, is extremely rare.

Alaïa’s vocabulary, like Guyotat’s, is at once powerful and subtle. His clothes are very beautiful. He has refused, since the very start of his career, to play by anyone else’s rules other than his own, flying in the face of the Establishment and the fashion system as if his existence depended upon it and, as it turns out, indeed it does.

On the 3rd of April this year, the space currently occupied by the Guyotat show formed the backdrop to a very different kind of presentation. The Paris Ready-to-Wear ended almost a month before it took place but, as is his wont, Alaïa chose to delay his show. The designer retired from the official schedule as far back as 1992. “It’s ready when it’s ready,” was the simple explanation behind any apparent tardiness this time, as always, according to his press office and as if it were the most natural thing in the world. It’s worth noting, however, that he is the only fashion designer who appears, long-term, to be in control of his own timing, often showing only days after the main event closes but certainly never in the throes of it. “I live with the climate. I am like fruit. When I’m ready, I’m ready,” he will say later. “There are no rules, it’s a way of life.”

In 2011, Azzedine Alaïa was rumoured to have turned down the position of Creative Director at Dior following John Galliano’s departure. Not long after, the designer told Women’s Wear Daily that the output now expected from many of the industry’s designers was “inhumane”. Anyone who has had any connection at all with the workings of Azzedine Alaïa – the company, the clothes and the man – will know that a respect for humanity is an integral part of the story. And that applies to everything, from the extreme loyalty displayed towards staff and reciprocated to the point of devotion, to the deep and lasting friendships he has formed over the years and on to the clothes themselves which, contrary to popular mythology, are by no means only designed for model bodies but for any woman who chooses to wear them. No two women look the same in Alaïa and that is important: Azzedine Alaïa suspends his ego and the client is always put first.

It seems only apposite, then, that the title of the Azzedine Alaïa Autumn/Winter 2016 show was “Le Défilé des amis”. It took place on a warm Sunday afternoon with only a handful of journalists and buyers in attendance. Instead, the emphasis, just as the words suggest, was on Azzedine Alaïa’s clients, family and friends. And that is different, unprecedented even. It’s all very personal.

In fact, Alaïa the business has recently been expanding. He launched his first fragrance with perfume-maker Beauté Prestige International last year. A warm floral made warmer still by the inclusion of orientals and musk, it is inspired, he has said, by water being poured over the heated brick walls of his place of birth: Tunis. Another is soon to follow. Alaïa also plans to open flagship stores in London and New York next year. He has taken his time in doing so. Also well known: Alaïa delivers to stores across the world only when he’s ready to deliver, and anyone lucky enough to receive his designs is happy to wait, safe in the knowledge that demand inevitably outweighs supply.

His new collection will be no exception. Alongside the requisite, impeccably engineered fit-and-flare knitwear for which he is most famous – it’s not for nothing that since the 1980s he has been referred to as the King of Cling – came black trapeze-line dresses in spongy techno fabrics inset with geometric shapes in the colours of the Tricolore (both French and Italian); tailoring that is, quite simply, unsurpassed – an immaculate black wool-crepe trouser suit, the perfect cashmere coat; and the most exquisite Swiss lace imaginable, in forest green, lavender, and damson, all lined in Alaïa’s signature pink and among the most gorgeous examples of the peek-a-boo aesthetic that lies at the heart of his vocabulary to date.

“There are certain parts of the body that it is nice to show,” is how he explains it. “I think that even when you make a zip, when I did the zip dress, for example, it was very important for me that the zip opened on a beautiful part of the body. It wouldn’t open on the fat side but always on the nice part. The zip exposes the stomach, which is lovely, and then the bottom, the bottom is beautiful too.”

At the end of this latest show, guests queued to congratulate the diminutive designer, dressed as he always has been in unassuming black, Chinese pyjamas and slippers (workwear, basically). M Alaïa is surrounded – mobbed – by women of all ages, shapes and sizes, all of whom know only too well the allure of his designs. The warmth, generosity and even happiness in evidence is a far cry from the studied nonchalance that might be expected of such occasions.

It should come as no great surprise that the interview process where Azzedine Alaïa is concerned is – similarly – unlike any other. Instead, and before any questions are asked, lunch is served at a huge glass-topped garden table in the basement of the same building. His boutique is at ground level, and Alaïa’s home and tiny, chic bed and breakfast hotel furnished with pieces from his own collection, 3 Rooms, are situated in the upper storeys on the same small street. The photographer Sarah Moon and Carla Sozzani, the designer’s creative consultant since 2000 and one of his closest friends, are in attendance.

M Alaïa is showing a book that features his work alongside sculpture by Bernini and painting by Caravaggio for an exhibition that took place in the Galleria Borghese in Rome last summer. Azzedine Alaïa is the first fashion designer ever to have had his work displayed there and if anyone is man enough to live up to the High Renaissance giants in question then it is he. Alaïa explains to the photographer how the blocks for his designs had to be elongated and the clothes remade to suit the scale of the work they were relating to and the proportions of the gallery. Also present is Alaïa’s right-hand woman and studio director, Caroline Fabre-Bazin – the pair are inseparable; the gallerist Yvon Lambert; the photographer Gilles Bensimon; the curator Donatien Grau; and what appears to be the designer’s entire staff.

“Où est Pudding?” asks the man himself, at the head of the table. Pudding is his archivist, another Sarah, who was offered the names “Yorkshire” and “Pudding” by her employer, he tells me, because she’s English. She chose the latter. The designer’s magnificent Saint Bernard, Didine – also renamed, this time after his owner – lollops about in search of titbits and he’s not disappointed. A piece of corn tempura finds its way into his intimidatingly enormous mouth, then a slice of veal… M Alaïa sleeps with Didine, although he points out that because he’s “a snow dog” he gets too hot, so rarely stays all night. Still, that evokes quite an image: the beast is significantly larger than the man. Satiated, he flops down at Alaïa’s feet.

It is impossible to imagine an atelier that is any more amicable or more family-oriented than this one. The scene is one of bustling activity, unparalleled bonhomie and excitable creative interchange. And that is just how Alaïa likes it. While taking care of his aforementioned four-legged friend, he drops in and out of conversation with all at the table ensuring everyone has enough to eat and drink – a full three courses – and that a good time is had by all. There’s a sense of the finest taste but also a balance between the light and the heavyweight, the understated and the generous, the polite and the warm. And that is all quintessential Azzedine Alaïa.

Fashion could reasonably be described as weak – and certainly disrupted – just now. It’s no secret that more than a few of the industry’s most celebrated names are financially compromised. But Azzedine Alaïa is strong. Not for him talk of consumer-facing fashion shows or merchandise available to buy straight off the runway. He has seemingly somewhat reluctantly agreed to produce a Pre-collection. In 2007 he entered an agreement with Richemont. The bottom line is important. Alaïa never has anything but good to say about the partnership. And Richemont is lucky to have Alaïa by return. In Alaïa-speak, Pre- is known as “la collection intemporelle” (the timeless collection). With the table cleared and coffee served, he says: “Fashion is arrogant, a reflection of our time – politically, economically. We have to try to understand why it is like that. We have to respect it even if it seems distorted. Today time is so accelerated and that’s not good for creation. We keep producing more and more. We expand. Sometimes I’m even against the timeless collection. I think it’s almost stupid. And when you see that you sell more of that… I find that not very good. Of course I would like to have more time for more fulfilling work. But I understand it. I accept it because it is the way it is.”

Alaïa can say that. He has worked longer and harder than most to achieve his goals. He is passionately committed to his craft. It is the stuff of fashion folklore that he cuts, pins and sews into the wee small hours before passing his designs onto the studio when their day begins. His studio is cluttered, to say the very least, so full of treasures that anyone even remotely interested in fashion could spend hours rifling through rail upon rail. Here is a tiny gold crocodile jacket moulded to fit an equally fine torso. Crocodile skin is tough and notoriously difficult to work with. To manipulate it to the point where it appears so malleable – almost seamless – is nothing short of genius. There is a ruby red silk velvet shift, so light, liquid and apparently simple that it is a thing of wonder to behold. There are knits. Of course there are knits: their surfaces peppered with tiny holes, sprouting raffia or feathered skirts or corrugated into three-dimensional textures that defy explanation. How does Azzedine Alaïa do that?

On his desk sit hundreds, even thousands of pins – the designer works on the body and row upon row of these, put into place by his own fair hand and at lightning speed, ensure garments fit just so. They are among the most important tools of his trade. Less predictably, a black rubber rat and a plastic figurine of Queen Elizabeth II can also be seen. Above it, on raw brickwork, hangs a board. Not for Azzedine Alaïa the mood board of fashion mythology. Rather, there are pictures of Carla Sozzani, Charlotte and Marc Newson, Stephanie Seymour and Naomi Campbell: the people the designer loves and who constantly inspire and motivate him are more important than any reference. Those all come from within. There’s a huge flatscreen TV too. While he works M Alaïa likes to watch the National Geographic, History and Voyage channels. The silence that was the preserve of Cristóbal Balenciaga in particular has no place here. Instead, the magic happens in an atmosphere of chaos, and not the most obviously organised chaos either.

Alaïa explains: “I grew up with my grandmother. She worked all the time. I was never alone. Every day there were 15 people in the house. My aunt, my cousins. Everyone came to my grandmother’s house because she lived in the centre of town. They all came from the lycée for lunch. With my grandmother, the door was never closed. Maybe it comes from that.” “His ability to focus in a mess is incredible,” Caroline Fabre-Bazin confirms.

To the people he cares for – and there are many of them – Azzedine Alaïa’s door is always open too. During the 1980s, when he went from being the best-kept secret of Parisian women of style to the brightest star on the fashion calendar, he looked after models in particular. They worked for him for clothes and he treated them as if they were his daughters – often somewhat errant daughters as it turns out. Naomi Campbell – who calls Alaïa “Papa” – met him during that period. “I met him and that was it,” she remembers. “He called my mother and told her I had to live with him. He said I shouldn’t be in Paris aged 16 by myself. He said I needed protecting and he was going to take me in.”

Not only was the model privy to what she describes now as “the best closet in the world – my closet was the shop” but she also says “he’s such a caring father figure”.

It wasn’t always plain sailing. “I used to sneak out at night to go to Les Bains Douche with Grace Jones and Iman,” Campbell continues. “I’d have to put my stuff downstairs by the door but the dogs would always start barking when I left so he would wake up and know I wasn’t at home. Then Papa would arrive. He’d get a call and they’d tell him, ‘Your daughter is here’. So he’d come down and look at me and if I’d put the outfit on wrong he’d fix it and then say, ‘Now you’re going home!’ I’d say, ‘No! Please Papa, can I stay?’ I remember one time Prince was going to come and play live, but he was like, ‘No. Home.’”

On another occasion, Campbell recalls, she fell down the stairs. “We had no ice in the house. We’d run out. But we had a frozen leg of lamb. I remember he put that on my head. Papa, if it was his last egg, his last piece of bread, he’d give it to you. To me he is family in every sense of the word.”

Just like any self-respecting father figure, at times Alaïa is honest to the point of harsh and, let’s not forget, that is not the way most people treat models, especially models as spectacularly successful as this one. “For years he told me, ‘Don’t wear too much make-up, you don’t need more make-up. Now finally I don’t wear so much but back then it was a security blanket.” Above all, and for all the intimacy of their relationship, “As well as having the most amazing heart, he is one of the most amazing designers, if not the most amazing designer in the world,” Naomi Campbell says.

Azzedine Alaïa was born in Tunis around 1940. No one is aware of his exact age: “Having tried hard, I forgot it,” is how he has long skirted the issue, which is his prerogative. He was brought up by his maternal grandparents in an environment that he describes as “poetic, lyrical. I had such a happy childhood”.

He used to dance for his classmates – and is not averse to doing so now – in return for pencils and was given more of these by the local midwife, Madame Pineau, whom he stayed with and assisted two nights a week. When we met more than ten years ago, he described his first experience of childbirth. While he had clearly told the story many times, it still animated him.

“Especially the first time, I was shaking,” he said. “Madame Pineau was working from home and one day when I came in I saw a woman lying on the table with her feet up in these things. Madame Pineau asked me to go and get some water and I could hear the woman screaming. When I got back, I saw a head between her legs. I was petrified. That’s when she slapped me to shake me up. Then she got the baby out and I watched her cut the umbilical cord.”

As well as her clearly adept delivery skills, Madame Pineau, whose husband was a doctor, was also well versed in the arts. “They used to have all these magazines about art galleries in Paris and books about painters like Picasso and Velásquez. I used to read them all and draw what I liked to remember. She also received a lot of fashion magazines: Vogue and catalogues from top department stores like Le Bon Marché and La Samaritaine. In the evening, after work, she used to sit next to me and place orders for clothes. When the boxes came, we opened them together. I was so happy. I can still remember the little printed cotton summer dresses, the white gloves, and the shoes.”

As a teenager, Alaïa enrolled at the local École des Beaux Arts, where he studied not fashion but sculpture. “I was lucky to realise soon enough that I would never make a great sculptor.” Instead, on his way to school one day he saw a sign in a dressmaker’s window advertising a job finishing hems for five francs apiece and took it. From there he found his way into the hearts of the grandes bourgeoises of Tunisian society, women who arranged a job for him making copies of Parisian haute couture designs (“Dior, Balmain. That’s how I discovered Balenciaga. I was very interested in his work.”)

Through these clients, Alaïa soon landed a job in Paris at Dior, then presided over by its namesake and his assistant – the young Yves Saint Laurent. Later, he spent two seasons at Guy Laroche. “At Dior I met the studio director Marguerite Carré,” he says. “She was an incredible woman. She symbolised my vision of the big technician. People like that don’t exist any more. I was all eyes. No one could understand what a young Tunisian guy like me was doing there.”

Today, Alaïa himself is not only one of the most knowledgeable sources regarding the history of mid-20th century haute couture, which he collects, but also just such a technician in his own right. He is one of only very few contemporary designers who can cut, pin and sew a one-of-a-kind garment from start to finish and who does so himself, albeit under the watchful eye of those who help run his studio. He cites Madeleine Vionnet; Madame Grès; Paul Poiret; Christian Dior; and Balenciaga as among the greats. “Vionnet was so modern: the concept, the cut, she brought so much to fashion.” And Chanel? “Styliste,” he comes back, with just the hint of a smile. It’s not intended as a compliment. “Even I am shocked by the prices for my haute couture though,” he says. “Caroline calculates it. I say to her, ‘You are mad!’ She says, ‘It’s the time. It’s the materials.’ Women come to be taken care of. When a client orders a couture dress we need to do something special. It’s normal. I’m not doing anyone a favour. It’s just the way I work. I need to see everything, even the first fitting. I have to check things. I have to make things.”

“This is priceless,” Fabre-Bazin chimes in. “He is priceless. And when they understand the mechanism of this relationship, when they understand that it is an experience... In the other houses the designer never comes.”

“The basis is always the woman, the body you dress,” Alaïa continues. “I’m not thinking about being fashion-y or revolutionary. I don’t think about making something that is ‘Alaïa’. I never think about that. I never thought about being a famous designer or a couturier. I admire women because it’s thanks to them that I do what I do. I’m not interested in the noise around fashion. When I make dresses for women, for my friends, and I see that I’m making them feel beautiful, when I see that they’re happy, I’m happy too. I am always happy to see women happy. If she’s getting married, she’s going to wear that dress, she’s going to have memories of it. It’s an important moment, a big thing, so I feel I should do as much as I can to make the clothes perfect. If a woman doesn’t feel good or at ease, it’s a lost evening, a failed evening. Poor girl!”

Fittings usually take place in the Alaïa boutique, behind heavy crimson velvet drapes, in front of a huge mirror. A portrait of Alaïa by his friend, Julian Schnabel, hangs at the back and can be seen in reflection as he works. Schnabel also designed the monumental bronze rails from which Alaïa’s clothes hang in the boutique. Marc Newson was responsible for the white display cases housing shoes, which are positioned to one side.

Ana Carolina Reis has been Azzedine Alaïa’s fit model for ten years now. Just as might be expected, she met him through a friend who was going for a casting. “I waited for her in the shop. I didn’t even have a book. Then they asked me to go into the casting so I tried something on. A few days later they rang the agency and we started.”

A decade on and at collection time Reis may work for Alaïa anything from two to 16 hours a day. “He makes everything on me, by himself, before it goes to the atelier. He makes the patterns, he pins. It’s fascinating. No one works like that any more. We talk all the time. He did my wedding dress. He made my fiancé come to him and said, ‘You have to ask me for her hand because I’m her father here so I have to agree to it.’ So he came, and he asked and M Alaïa said, ‘I’ll think about it. I’ll call you.’ I was like, ‘Oh my God!’”

Luckily, “He really likes him. We always go for dinner with him. It’s like we became a family. We all eat together. Sometimes, he cooks. I know everyone there. The girls that clean, the girls that cook, the commercial team. And he gives me presents all the time. I have an entire closet of Alaïa: Alaïa dresses, Alaïa shoes, Alaïa bags… Depending on his mood he may talk about my parents or my husband. ‘How was your day?’ Or sometimes he puts on Beyoncé or Shakira and he dances. He’s a super-good dancer. He has a swing that goes down to the floor.”

If there is an intensity to Azzedine Alaïa’s unrivalled work ethic – “I live only for my work” is something he says more than once – it is also clear that he likes to have fun. He always has done. In 1960, through a contact from home, Alaïa, who had been making money as a housekeeper to survive, went to work for the Comtesse Nicole de Blégiers. For her he cooked Tunisian dishes and took care of the children. He applied himself to this with just the same enthusiasm as everything he has ever touched, by all accounts. Legend has it that she once returned home to find Alaïa fully dressed in the tub, bathing the baby. Through this family Alaïa met Cécile de Rothschild and her close friend Greta Garbo. Garbo came to him not for a dress but for a navy coat. “She had been everyone’s fantasy and there she was in front of me,” he told me. When the coat, which was oversized – “big, bigger, biggest” – was finished, the actress thanked the couturier “very sweetly” and said he had “nice, good eyes”. And so he does, hugely expressive, dancing with merriment and often mischief though gentle too: kind eyes.

Throughout the Nineties, Alaïa maintained a relatively low profile, designing his collections quietly and showing them in the intimate manner that he still prefers, all while continuing to dress clients in Alaïa haute couture. Not that he has ever been anything even remotely resembling the shrinking violet. In 2009, seven models including Naomi Campbell, were planning to wear Alaïa to the opening of “The Model As Muse” exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute. Remarkably, given Alaïa’s relationships with every Super worth her credentials, aside from one photograph by Gilles Bensimon, his work wasn’t featured. Alaïa blamed Anna Wintour: “She has too much power over the museum,” he told The New York Times at the time. Campbell chose to boycott the event. “I will never be part of anyone or anything that’s disrespectful to my papa,” she says.

Alaïa’s business is bigger now than it was then and it is testimony to his integrity that, in an over-saturated market where so many others struggle to maintain their identity, it remains just as special – just as desirable – as it always has been. And the man behind it all loves his work just as he always has done, too.

Azzedine Alaïa continues to learn though, through his friends, among them architects, artists, industrial and interior designers, photographers, writers… “I’m always curious,” he says, and it’s notable that throughout this interview he asks as many questions as he answers. “When I wake up in the morning, I brush my teeth and then I think, ‘Who am I going to meet today, which new people, and what am I going to learn?’ Because I’m always an apprentice. My friends are very important to me. When I love my friends, I love them with the deepest love. I have been lucky enough to have profound friendships and there are new friends coming too. I learn from them all.”

If Alaïa’s friends share anything in common then it is independence, the desire to express themselves with complete freedom and as much as possible in their own way. “Absolutely independence means you can be free” he argues. “Even if I was in prison I would be free. It’s in the head, in the thoughts. I’m always working. I’m locked in my work but I have friends who come to visit me and they teach me things.”

As well as the gallery, he is currently moderating discussions between such creatives – many of them luminaries in their respective fields – on the subject of time, due to be published in book form soon. “Time touches everyone and everything. It interests me because I discover time with all the people I’ve met, they’re all interesting people, important people, people of all ages. And you see everyone is different in the time they live. The street is very interesting for me too. You can stay inside but you have to go outside and look at different generations. The children of my friends, young women, it’s important that you go forward in your work. You can learn from them too. Young people are the future. The past, we know it. We live in the present. The future is obscure. But time is a very important issue. People need to be aware of it because they shouldn’t waste time. If they’re aware of it, they won’t waste it,” Azzedine Alaïa says.

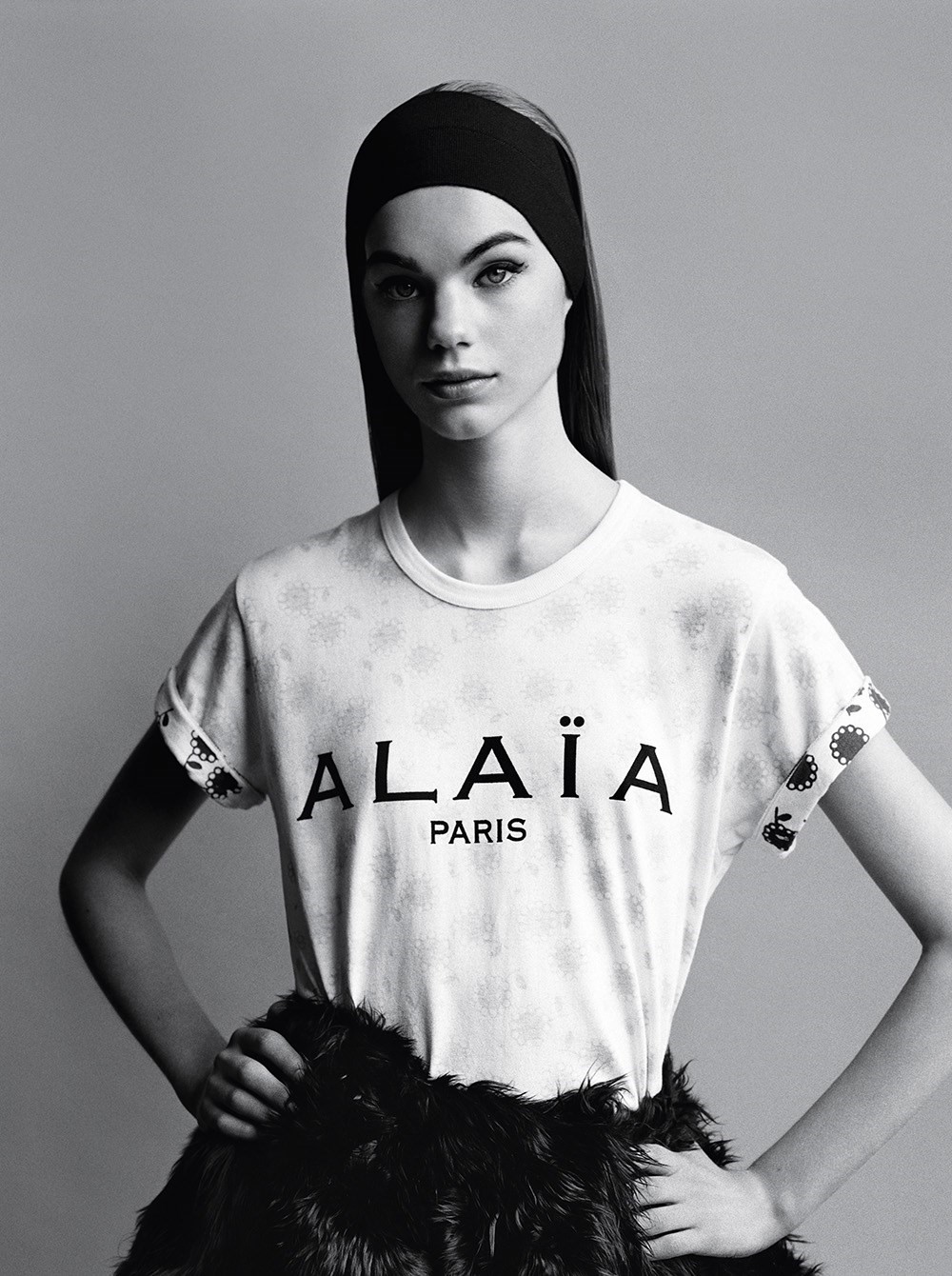

Additional interviews Olivia Singer; Hair Malcolm Edwards at Art Partner; Hair for Naomi Campbell Cyndia Harvey at Streeters using Oribe; Make-up Miranda Joyce at Streeters using Bobbi Brown; Make-up for Naomi Campbell Alex Babsky at Jed Root using Lancôme; Models Ana Carolina Reis at Women Management, Ava and Stella Jones, Ella Merryweather at Tess Management, Estella Boersma at Viva Model Management, Iris and Rafferty Law at Tess Management, Izzy Davis, Jess and Reba Maybury at Elite Models, Kate Moss at KMA and Lila Grace Moss, Livvy Banks, Matilde and Otto Rastelli at Elite Models, Naomi Campbell at Tess Management, Susie Cave at Premier Model Management, and Yasmin Wijnaldum at Elite Models; Casting Jess Hallett at Streeters; Set design Poppy Bartlett at The Magnet Agency; Manicure Marian Newman at Streeters using Vinylux Sweet Squared; Manicure for Naomi Campbell Liza Smith using CND; Photographic assistants Lex Kembery, Matthew Healy, and Simon Mackinlay; Styling assistants James Campbell, Lydia Simpson, and Aurora Burn; Hair assistants Sophie Anderson and Becky Dobney; Make-up assistant Hannah Maestranzi; Manicure assistant Jennie Nippard; Set design assistant Roxy Walton; Casting assistant Caitlin Prosser; Producer Ragi Dholakia; Production manager Claire Huish; Production assistants Kyal Crase and Jordan Kilford; Special thanks to Output London.

This article originally appeared in AnOther Magazine A/W16.