Remembering the ethereal heiress, muse and patron of the arts that Augustus John once claimed should be "shot, stuffed and displayed in a glass case"

With a gift for malice and a penchant for exhibitionism, Marchesa Luisa Casati is the kind of figure so swathed in myth that she defies definition. In her heyday, she wandered Venice in nothing but a fur coat, accompanied by her pet cheetahs on diamond leashes. She threw parties attended by Pablo Picasso, Man Ray and the dancers from the Ballet Russes, in rooms decorated with Egyptian statuary, crystal balls and lions borrowed from the zoo. When her jewellery box held nothing suitable, she'd don her boa constrictor, or have white peacocks become an accessory for her elaborate costume.

Casati was born Luisa Adele Rosa Maria Amman in 1881, and grew up near Lake Como in Italy. She was was one of two daughters of parents who had made their fortune in the cotton trade: Casati’s father had been ennobled in 1887 but died five years later, his wife following within 12 months – and so, at the age of 15 she became a much sought-after heiress.

Within four years Casati was married to Count Camillo Casati Stampa di Soncino. It wasn't until she began following the European hunting circuit, however, that the young Luisa met the poet Gabriele d’Annunzio, with whom she had an affair that sparked her transformation into a femme fatale and muse to the avant-garde.

Defining Features

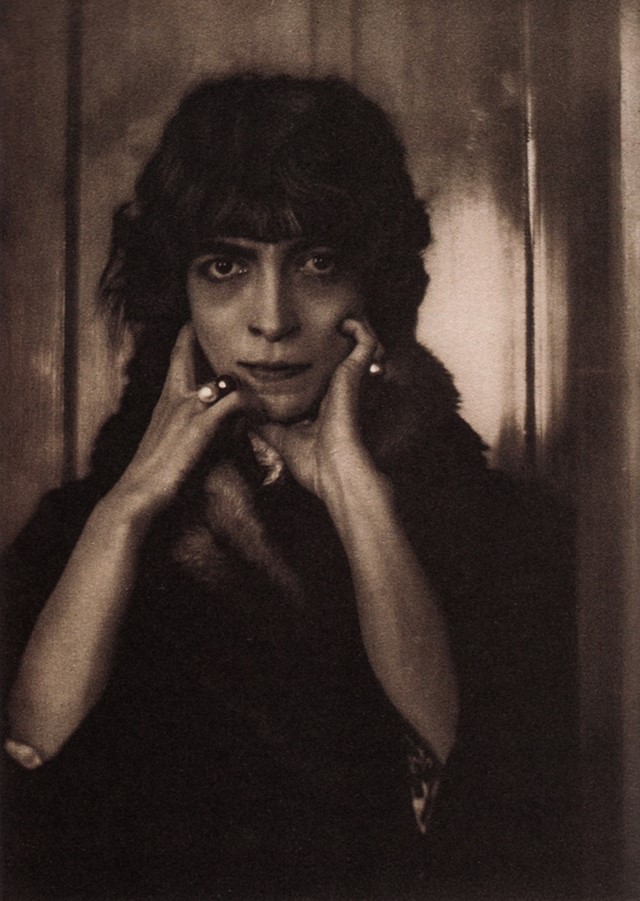

The Marchesa came to form the archetype of the female dandy, standing at six feet tall in spite of living on a diet of gin and opium. Her skin was bleached white, and made to look even paler by the doses of belladonna, a plant-based supplement which often proved poisonous, that she took to keep her pupils dark and dilated. To accentuate the effect she wore black kohl around her eyes, with false eyelashes and strips of black velvet glued to the lids.

She separated from the Count in 1914 due to her need to live freely, and took a home in Venice – an unfinished palace called the Palazzo Venier dei Leoni, built in the 18th century on the Grand Canal – which, years later, would become home to another heiress: Peggy Guggenheim. Here she lived with a motley crew of people and animals: a host of gold-painted servants, a pet boa constrictor, mechanical birds in gilded cages, an ostentation of white peacocks and a coalition of cheetahs with diamond collars.

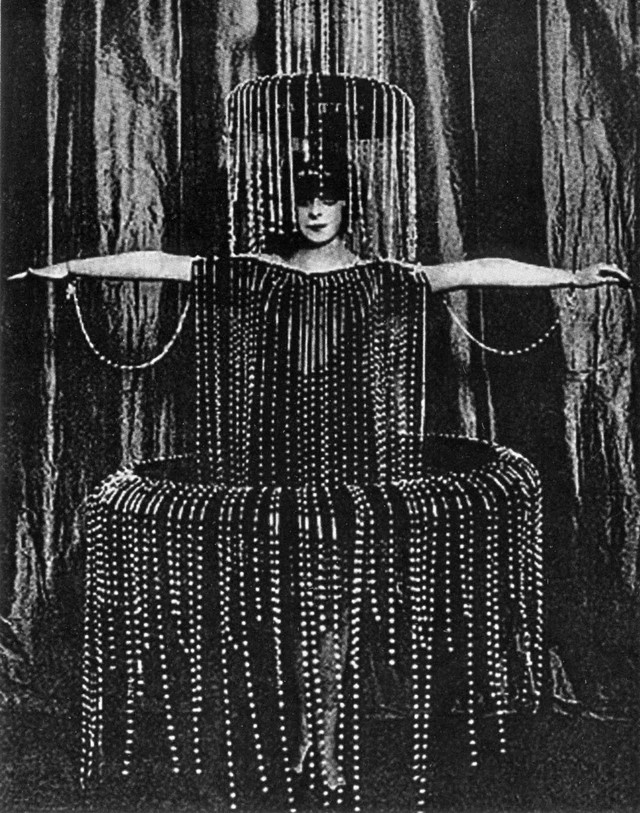

Casati's singular aim had always been to become a living work of art, and she achieved it through multifarious means. Her garb grew ever more elaborate with each social gathering, her most famous being a dress made of lightbulbs and powered by a generator. Determined to preserve the legend she had worked so hard to create, she assembled a vast collection of portraits of herself that she would exhibit in a detached pavilion at her Paris mansion.

Seminal Moments

The Marchesa's life was a continual reaction to her horror of the mundane. By perpetually transforming herself and her homes she continued to outdo herself, becoming an object of endless fascination for the artists of the era in the process. Over the course of her lifetime she was a muse to Jean Cocteau, Cecil Beaton, F. T. Marinetti and Erté, and modelled for drawings, sculptures and photographs by the likes of Man Ray, Giovanni Boldini and Romaine Brooks.

By the time the Depression hit, Casati's parties had fallen into bad taste, and her empire of dreams had begun to crumble. She had spent her inherited fortune on palaces, parties, antiques, cars, clothes, jewels, travel and art, racking up a debt of $25 million. After the forced liquidation of her villas and their contents she moved to London, to a bed-sit close to Harrods. From here she would cast spells on her enemies and drink away the last of her funds while writing an incomprehensible journal, and could also be found rummaging through bins in search of feathers to weave through her hair.

When she died, the Marchesa was found by a friend who had visited earlier that morning for a séance. Having let himself back into her flat he took her embalmed Pekinese dog for safekeeping. She would be buried with him a few days later, wearing a leopard-trimmed cape and a fresh pair of false eyelashes.

She’s Another Woman because...

Marchesa Luisa Casati’s was a life devoted to art. She was in herself and in her creations an unforgettable spectacle, and although by the time of her demise she had ceased to live a gilded existence, her legacy was not about to fade away. In life she had made every facet of her existence challenge convention and mediocrity, and as a result she was immortalised in art, film and the gossip columns of newspapers the world over. She continues to inspire in death, as in life: since her passing, her influence has been seen in the work of John Galliano, Alexander McQueen, Karl Lagerfeld, and in Georgina Chapman and Karen Craig’s label Marchesa, amongst many others.

Now, the Marchesa Luisa Casati’s body lies buried at Brompton Cemetary, where her gravestone is inscribed with a quote from Shakespeare’s Anthony and Cleopatra: “Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale her infinite variety”. A fitting tribute to a truly inimitable character.

With thanks to The Casati Archive.