Curator Shonagh Marshall explores three key historic moments celebrating gingham; from Miu Miu to Biba, Comme des Garçons to wartime fashion

“Really, Miu Miu was about irrationality,” Miuccia Prada said to Sarah Mower about Miu Miu S/S16, of its medley of layers and gingham buttoned-up shirts and jackets, of its skirts in different colours of the same fabric paired with sheer wrap dresses which evoked pinafores or aprons – the domesticity of the gingham fabric and its roots in use for tablecloths, dishcloths, or curtains, came to the fore. The word gingham entered the English language in the seventeenth century; originally it was a striped fabric imported from India. However, in the mid-eighteenth century, when Manchester mills started producing the material, it was woven into checked or plaid patterns. A plain-woven cotton cloth the colour is on the warp yarns and always along the grain (weft). Inexpensive, it has been used for the aforementioned home items, but also for toiles, which are a test version of a finished garment made in a cheap fabric. The history of the fabric is vast, but here we trace its ubiquity through three seminal moments, singling out its use in wartime, its importance in the sixties youthquake movement and as an elemental part of Comme des Garçons’ nineties body morphing.

The Wartime Dorothy

The model perches on a red large check tablecloth, her two-colour gingham day dress, designed by Adrian, seemingly extends the line of the table creating an optical illusion. The neatly-tucked bustle rests on top and the band around her middle, of the same fabric, embellishes her waist. The sun pours through the window and bounces off the glasses of red wine on the table, evocative of a perfect summer afternoon. Adrian was the in-house costume designer at movie studio MGM from 1928 until 1941. Designing costumes for stars such as Jean Harlow, Norma Scherer, Joan Crawford and Greta Garbo, he is best known in popular culture for designing Dorothy’s gingham pinafore in the 1939 film The Wizard of Oz. This dress, shot by John Rawlings, sees him revisiting the fabric. Readily available and affordable during the war, Adrian shows his ability to seam and piece graduations of fabrics, varying their placement, into endless pattern variations.

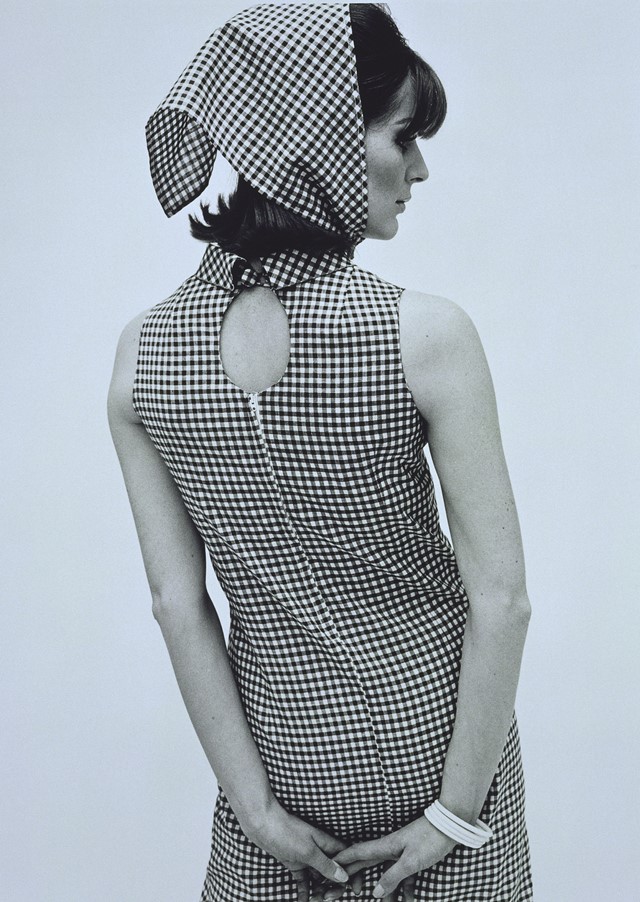

The Biba Game Changer

Pauline Stone, hands clasped underneath her buttocks accentuates the simple shift shape of the gingham dress. Her head, turned right, ensures the fall of the kerchief, worn tied under her chin, is perfectly framed by the camera’s lens. The hole at the top of the zip provides an interesting detail, just as Miss Felicity Green had requested. One Tuesday morning in 1964 Barbara Hulanicki received a call from the Daily Mirror; the fashion editor Felicity Green was doing a feature on young career women and would like to include Hulanicki, who had recently started a postal boutique called Biba. Miss Green asked for a design specifically for the article, which could be sold for 25 shillings. The resulting image, shot by John French, shows the chosen design, a sugar pink gingham sleeveless dress, from the back. In the following days after the piece ran the Biba postal boutique received seventeen thousand orders for this design. At the time when there was no clothing specifically designed for the young, it captured a zeitgeist.

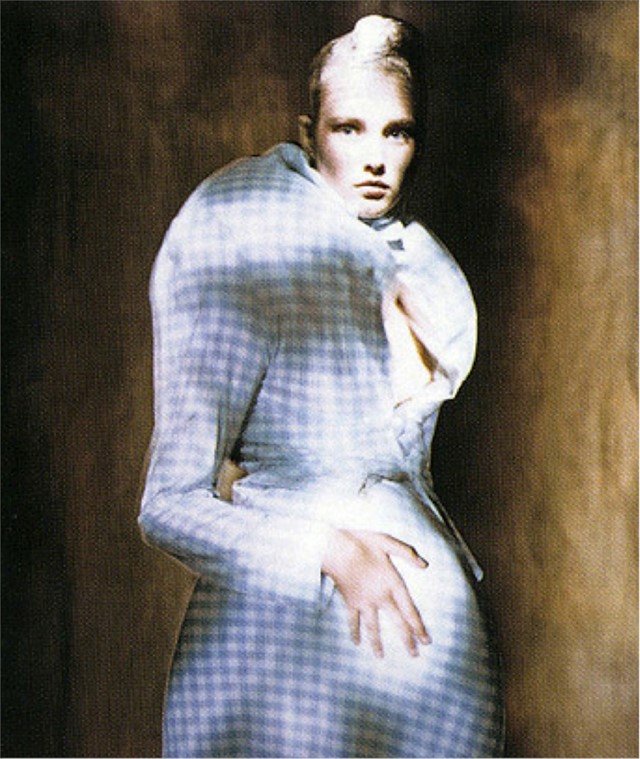

The Subverted Check

Photographed by Paolo Roversi in his distinctive painterly technique, the ensemble presented is fashioned from a power blue check and instantly reminds us of the light blue gingham uniform worn by primary school children in the United Kingdom. The bulging wads of down shape the shoulders to unnatural proportions, the model's hand nonchalantly rests on a lump protruding from her stomach. “It’s our job to question convention,” the Japanese designer Rei Kawakubo told Vogue after her Spring 1997 collection debuted: “If we don’t take risks, then who will?” The collection, entitled ‘Body Meets Dress, Dress Meets Body,’ was an exploration into the way in which clothing can transform the body. The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute has a holding of one of the dresses from the collection; they attribute the material to nylon, polyurethane and down. Not made from a traditional gingham fabric, the check is a surface detail – but, by this point, we have come to associate the word with the check instead of the material. This is somewhat irrational as when the word originally entered the English language it was striped and not checked.