Over the past season, it has been impossible to have a conversation about fashion without a broader topic cropping up: the fate of the ever-accelerating industry itself. Prada’s story of womanhood? Let’s discuss the A/W16 bags available to buy in March. Rick Owens’ post-apocalyptic futurism? Well, it was hand-draped, a statement of intent against the frenzy. Suddenly, the world (or at least, our little niche within it) has become consumed by the stock prices and e-commerce sales of the names whose creativity was once the focus of discussion. While this is all very pragmatic – and great fodder for an op-ed or news story – it peels away at what one would hope actually sustains the industry: the intangible magic summoned by a particularly special fashion show, the painstaking craftsmanship that might go into a showpiece, or the narratives that exist behind a collection.

The antidote to this general furore seems to be found within the legions of new designers currently cutting through the noise. Without shareholders or ancillary lines, they somehow exist outside of this corporate fashion conversation; they don't have time to create more than a couple of collections a year and they certainly won’t be subscribing to see-now-buy-now because they simply can’t afford to produce the amounts. One of the names at the forefront of this new era is Grace Wales Bonner, whose ascent into industry renown (she’s won a bevy of awards, been nominated for LVMH and designed for FKA twigs before her eponymous label is even two years old) has been nothing if not efficient – but her methods and motivations are worthy of more laboured consideration, and whose determined resolution to "not suffocate the work and just give myself time to develop" is certainly paying off.

A Modern Afrofuturism

Born in South London to an English mother and Jamaican father, Wales Bonner’s sartorial meditations on identity are as much to do with her own personal narrative as they are those which surround her: growing up, she wasn’t black enough to be ‘black’ nor white enough to be ‘white’. But, by interweaving references as disparate as Langston Hughes, Blaxploitation and Essex Hemphill, Wales Bonner fabricates her own historic narratives in a world that often prescribes black cultural experience: a contemporary development on the Afrofuturist tradition of interweaving reality with fantasy. "I looked at history, at representation, and at artists who had negotiated different realities," she explains. "And I used that to understand and validate my own experiences. There's a pre-arranged interpretation of history but you don't have to be tied down to it; you can propose that reality is what you want."

For S/S16, she paired 19th-century orientalism and depictions of North East Africa (with all the “softness” and “regalness” of its exoticism) with Indian Ocean aesthetics, inspired by the transitional narrative of Malik Ambar – an Ethiopian slave who was transported to West India before founding his own empire. The accompanying zine she produced, Everythings For Real II, featured cut-ups of academic theses interspersed with song lyrics and advertisement text: it was Sun Ra meets William Burroughs, a constructed and fantastical history of blackness. Post-colonial theory often concentrates on the idea that history is written by the winners (those winners generally being straight, white men) – and Wales Bonner was overwriting that narrative, refiguring black history into her own story.

"A current that flows from the ancient past and carries us away on a journey to a future way out beyond the galaxies" – Wales Bonner, A/W16

Her newest collection for A/W16 equally riffed on this idea: the show itself opened to the sounds of classically-trained Nigerian-Irish composer Tunde Jegede acting as a "master of ceremonies" or "griot" as he gently played the kora; it was a performance rooted in the West African ancestral tradition of connecting people to their lineage. The collection was “an interpretive history,” or, as the show notes read, “a meditation on black spirituality, a current that flows from the ancient past and carries us away on a journey to a future way out beyond the galaxies,” a utopic imagining of otherworldly racial harmony explored through seventies sportswear and Swarovski shimmers. When Sun Ra or Janelle Monae forged their own, extra-terrestrial identities independent of colonial narratives or human reality, it was an effort to reclaim an apocalyptic black history which transported African people away from their roots through the slave trade – as Professor Valorie Thomas writes, an investigation into “what it means to rearticulate the body that has been dissected, that has been mutated and that has been made to perform.” Wales Bonner’s collections act similarly: assimilating assorted facets of colonialist history to make one of her very own.

The Provocation of Beauty

What is so astonishing about Wales Bonner’s work is that, alongside its intricately woven histories, it is alarmingly beautiful: all careful tailoring and perfect embellishment. It is graceful and elegant, its message simply part of a beautifully presented package rather than whole lot – but that beauty seems, too, to be part of her statement. “Kerry James Marshall is my favourite painter,” Wales Bonner explained. “His work is very enticing and beautiful, and also it’s really large. The way he sees it is that, when he shows his work in galleries, he needs a lot of space – you can’t just walk by his work, you need to stop and look. When people do stop and look, they’re going to be staring at his portrait of a black person because it’s so captivating. I like to create beautiful things, that’s one thing, but I also want to do something meaningful.” This idea, of black people literally taking up space in fashion – a space that is often only filled by tokenism, if at all – is a particularly pertinent one following some tense conversations around the casting of womenswear fashion weeks. It’s particularly interesting when it comes to Grace Wales Bonner’s A/W16 collection because she only used one non-black model on her runway – and yet the image of him is the one that travelled the furthest when people wrote about it. The fashion industry is determinedly Eurocentric, visibly skewed white, and succeeding within it as a designer who celebrates blackness, black culture and a personal understanding of black history is something of a statement in itself.

"I like to create beautiful things, that’s one thing, but I also want to do something meaningful” – Grace Wales Bonner

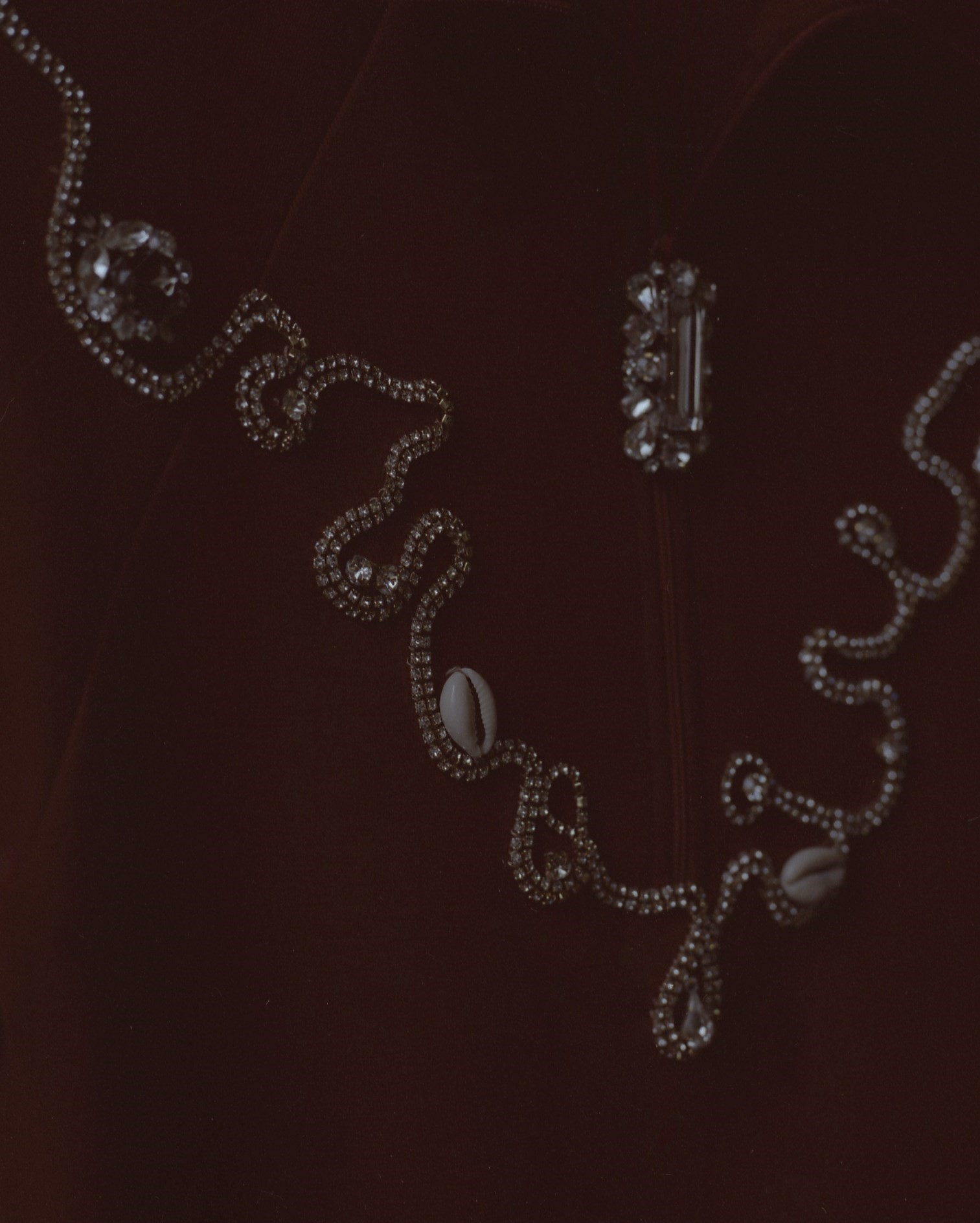

Wales Bonner’s exploration of black male beauty is one which sits determinedly outside the tired stereotype of street culture: hers is one that celebrates softness, beauty and elegance. One of the dominant issues within fashion’s casting of black models is that, all too often, the only men hired by agencies fit into a very specific mould of masculinity: stacked and athletic with hard, pin-up bodies. This is something that Wales Bonner has emphatically challenged throughout her career thus far, not only through her casting (a mix of boys from everywhere from Sierra Leone to Uganda, who she terms "brothers coming from like a different galaxy"), but equally the garments themselves. The signifiers of wealth often associated with black rappers – the diamond-encrusted chains and blingy rings – were transformed during S/S16 into a traditional currency of cowrie shells hand-stitched onto crushed velvet; this season, it was delicate crystals sitting on the waistbands of track-pants and necklines of zip-up jumpers. "When I was resourcing a lot of crystals, it was quite symbolic," she says, "I wanted to look at ‘wealth’ or the ‘currency’ of luxury." For those who choose to look behind the sparkle, there is something to be found; for those who don't, there's plenty to look at.