We trace the icons that queered the gender binary: from Marlene Dietrich and Elvis to Genesis P-Orridge

Over recent seasons, conversations around gender have permeated the fashion industry; binaries have been queered on runways from Milan to New York, from Prada and Gucci to Vetements and Hood By Air. There is a new, mainstream understanding of the performativity of gender and its construction by society – but this subversion of stereotypes is actually nothing new at all; it's been explored on paper by pioneers like Radclyffe Halle and Virginia Woolf, in the wardrobes of Marlene Dietrich and Boy George. As Halberstam writes in seminal text Female Masculinity, "Ambiguous gender, when and where it does appear, is inevitable transformed into deviance, thirdness, or a blurred vision of either male or female." Here, we trace some of the pioneers from the last century, those who transcended binary norms and subverted mainstream gender presentation; those who didn't just subscribe to tomboy status or imitate femininity, but refigured the categories themselves...

Radclyffe Hall

The novelist Radclyffe Hall played a similar role to the renowned Oscar Wilde, by both using the characters she wrote as well as her own personal style to subvert expectations placed upon her gender. While Wilde is commonly acknowledged to have brought dandyism into the mainstream, Hall is often forgotten for her equivalent impact on female dress: eschewing the glamorous femininity expected of upper-class ladies for suits and sideburns. While she was not the only woman diverging from normativity, she was a public advocate for alternative modes of self presentation and a self-proclaimed “congenital invert” (sexologist Havelock Ellis’ term for a lesbian), thus her role in disrupting conventions of both gender and sexuality is an oft-forgotten but vital component in the history of queering.

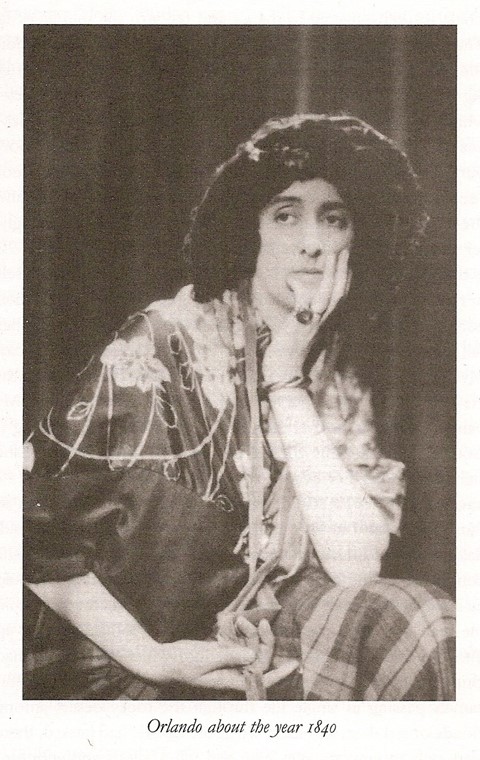

Virginia Woolf's Orlando

There are few narratives which explore the queering of gender quite so elegantly as Virginia Woolf's Orlando, a novel which traces the life of a nobleman through a 300-year lifespan. The story is based on Woolf's own lover, Vita Sackville-West, whose son famously proclaimed the masterpiece “the longest and most charming love letter in literature, in which [Woolf] explores Vita, weaves her in and out of the centuries, tosses her from one sex to the other, plays with her, dresses her in furs, lace and emeralds, teases her, flirts with her, drops a veil of mist around her.” The ambiguity surrounding both gender and sexuality within Orlando establishes it as one of the world's greatest queer texts – but perhaps most interestingly in this context is how Woolf subverts gender essentialism: it is clothing, rather than her body, which defines Orlando's understanding of herself. "It is clothes that wear us and not we them" writes Woolf. "We may make them take the mould of arm or breast, but they mould our hearts, our brains, our tongues to their liking... often it is only the clothes that keep the male or female likeness, while underneath the sex is the very opposite of what it is above."

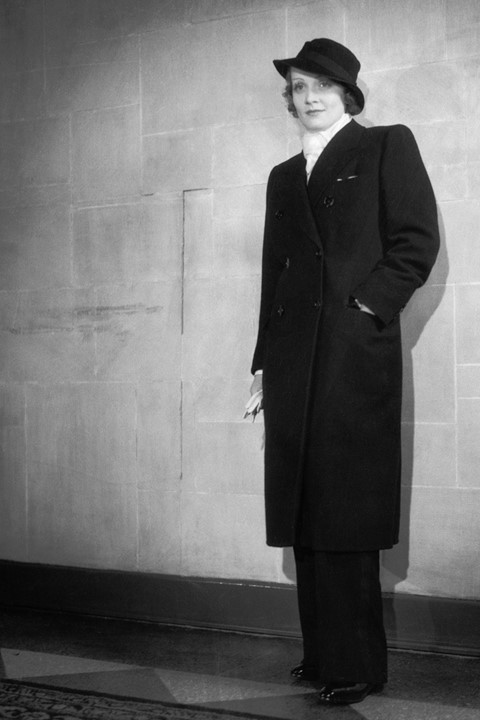

Marlene Dietrich

When Marlene Dietrich attended the 1932 premiere of Sign Of The Cross, she did so wearing a fabulous mens' tuxedo – in spite of the public transgression it signified. Openly bisexual, Dietrich was an incredibly progressive figure both in fashion and cultural politics; she was the first woman who embraced the Chanel-designed, two-piece suits of 1933 (which were even fabricated from mens tweed). "I am sincere in my preference for my men's clothes – I do not wear them to be sensational," she proclaimed. "I think I am much more alluring in these clothes" – and she was right; her approach to 30s glamour, which combined traditionally masculine tailoring with fur stoles and coiffed hair stands as one of the most-referenced approaches to gender queering (later imitated by the likes of Madonna) and brought female trouser suits into the mainstream spotlight.

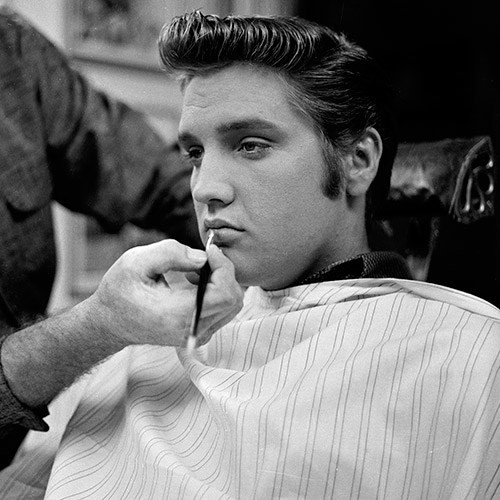

Elvis

When Elvis propelled himself to fame in the 1950s, it wasn't just his electrifying on-stage antics that shocked the world, but equally his use of conventionally feminine accoutrements like mascara and lipstick. His dedication to transformation and proclivity for sequins was considered morally corrupt by conservative masses: his emphatic sexuality compounded with his visual femininity destablised the previously rigid understading of desirable masculinity, and set the scene for plenty of havoc to come.

Calamity Jane

The story of musical Calamity Jane is a slightly bizarre one – it features a man performing in drag (which shocks the on-screen, hyper-masculine audience of cowboys into a riotous frenzy) alongside a tomboy Doris Day attempting to engage with conventional femininity in order to ensnare a man. Based on the actual American frontierswoman Martha Jane Canary – who was known for wearing traditionally masculine clothing to fit in with her fellow 'patriots' rather than out of an innate desire – in spite of its patronizingly conformist ending, what Calamity Jane reveals is the performativity of gender: that femininity is a social construct that needs to be learned by Calamity rather than one that is innately present within her. As critic Eliott Savoy explains, "The stubborn insistence of Doris Days’ queerness remains far in excess of the narrative’s heterosexist attempts at containment and 'feminization'," and the film actually showcases a subversion of gender in true technicolour.

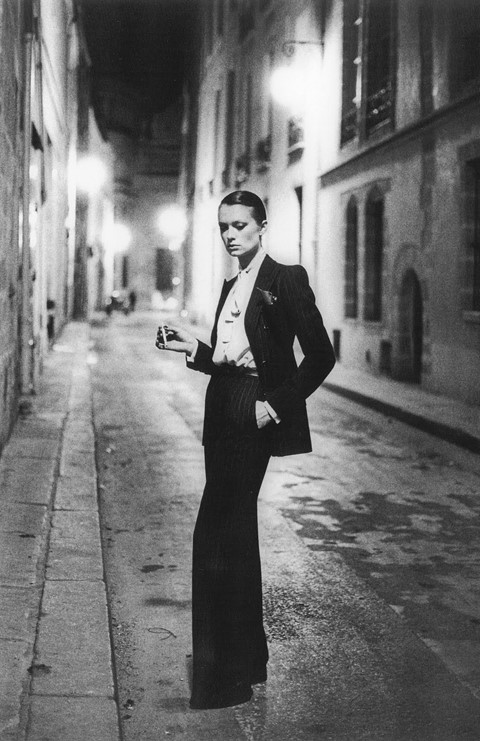

Le Smoking

When, in 1966, Yves Saint Laurent designed 'Le Smoking' – a tuxedo for women – it irrevocably shifted the fashion landscape, offering a new model of sexuality for women: one which didn't rely on an exposed and stereotypical femininity. Incorporated into the wardrobes of women including Catherine Deneuve, Lauren Bacall and Bianca Jagger, it was when it made its way into French Vogue in 1975, shot by Helmut Newton, that it achieved an immutable cultural presence; as Tish Wrigley writes, "It was undoubtedly photographer Helmut Newton who made Le Smoking iconic; his extraordinary capacity to imbue his subjects with a potent sexuality reaching new heights when married to the louche enigma of the YSL tuxedo." Le Smoking – and its subsequent interpretation by Newton – refigured female appearance as a powerful force rather than a submissive presence, and liberated it from the confines of convention.

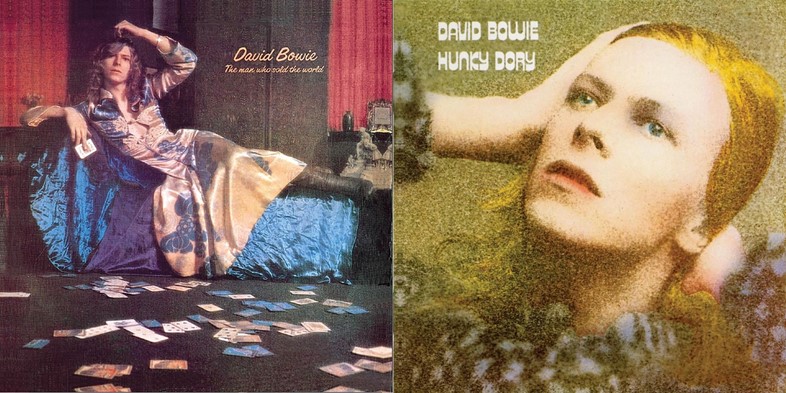

David Bowie

Throughout his career, David Bowie's approach to gender has been renowned for its subversion and fluidity, his varying on-stage personas appropriating the traits of historically avant-garde figures from Marlene Dietrich to Elvis Presley. On the cover of The Man Who Sold The World, he dresses in drag; for Hunky Dory he channeled Greta Garbo – and he consistently embraced cosmetics and clothing as transformative devices. "No one has surpassed Bowie as gender bender" wrote John Savage in The Face back in November 1980. "If Bowie has invented a whole language of ‘art’ posing, he’s invented more specifically the language to express gender confusion... David Bowie has entered British life as the model for every kid who says I wish I was…" And perhaps this was one of the key components to his success: his presentation of the boundless possibilities on offer. In his world, one could perform as whatever gender one chose – male, female, the otherworldly sex of Ziggy Stardust... everything was on offer, it was only what you chose that mattered.

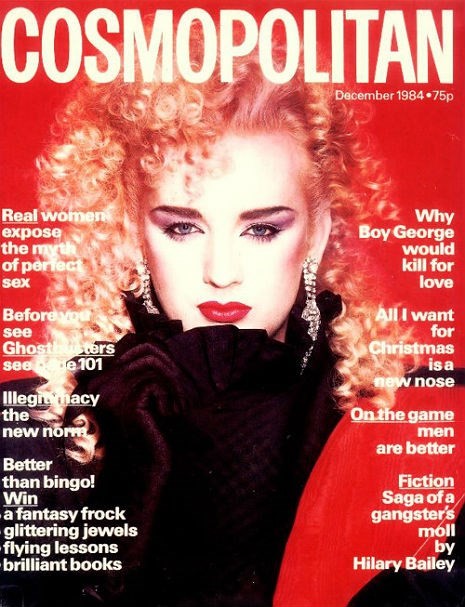

Boy George

A conversation about queering gender would not be complete without the mention of Boy George, whose blurring of categories was seen as threatening enough to rile the anger of American talkshow host Leslie Stahl. Stahl condemned him as part of “the Feminization of America” – a statement to which Boy George responded that sexuality and the clothes one wears are mutually exclusive elements, and that his appearance was both male and female. His mesmerisingly beautiful appearance, enhanced with a generous use of cosmetics (apparently applied with fingers – he once told Fuse FM that he was too poor to afford brushes back then) came to epitomise the New Romantic movement, an era characterised by its brilliant flamboyance, and established him as one of the key icons of queer culture.

Annie Lennox

When, in 1983, Annie Lennox appeared in the video for the Eurythmics' Sweet Dreams Are Made Of This, it was wearing the same jacket, shirt and tie as fellow bandmember David Stewart. With her cropped orange hair and the masculine cut suit, she made for an impactful presence – but she explained in the Observer, her androgynous appearance was nothing to do with sexuality but rather than she "didn't want to be perceived as a girly girl on stage. It was a kind of slightly subversive statement and what's even more subversive about it is that I'm so not gay." What renowned gender theorist Judith Butler explains in her book Gender Trouble is that gender performance is a strategy of resistance and "dramatize[s] the signifying gestures through which gender itself is established" – that there is nothing about subversion that innately connects with sexuality, but rather cultural rebellion and aesthetic inclination.

The Pandrogeny Project

And finally, and perhaps the ultimate example of the theme, is musician Genesis P-Orridge's collaboration with h/er wife, Lady Jaye. P-Orridge identifies as third gender and, in 1993, the duo commenced the Pandrogeny Project – which consisted of them both embarking on $200,000 worth of surgery and hormone therapy to homogenise their two appearances, so that they could unite as one 'pandrogenous' being under the name of Breyer P-Orridge.

"In January 1996, we arrived as husband and wife," P-Orridge explained to The Village Voice in 2011 about their arrival in Queens, "me still dressing and technically behaving male, and all the local shopkeepers who knew Jaye from being a kid, all the neighbours, being like, 'Oh, you're the husband! We've heard about you.' And then over the years, we transformed more and more until we were both running around in miniskirts, dressed the same, and none of them said anything! Except in the pharmacy, where very politely, one of the Pakistani guys we knew very well there – we talked about cricket with him, because he loved to talk about cricket—and he says one day, 'Hope you don't mind me asking, but you probably want us to say "Miss P-Orridge" now, don't you?' We said, 'That would be good!' And that was the one time anyone even mentioned that anything had happened."

Their extreme exploration of the ultimate manifestation of gender queering – defining and embodying a new gender – was tragically interrupted by the death of Lady Jaye in 2008 but, as P-Orridge's website proclaims, "Since that time Genesis continues to represent the amalgam Breyer P-Orridge in the material 'world' and Lady Jaye represents the amalgam Breyer P-Orridge in the immaterial 'world' creating an ongoing interdimensional collaboration" – theirs is a project transcending not only gender but the very confines of human existence.