AnOther explores the powerful manipulation and subtle rebellion of style in a totalitarian state; from Orwell's 1984 to Mussolini's Italy

In George Orwell’s dystopian novel 1984, an oppressive and omnipresent super-state watches over the behaviour of its citizens, whose activities, dress, morals and even thoughts are strictly policed. One of the more tender plotlines is the love affair that protagonist Winston Smith has with fellow worker Julia – although affairs (and the privacy required to carry them out) are not allowed, the couple meet for a secret rendezvous, breaking additional rules by being in possession of exciting sensory contraband like coffee, sugar and white bread. Julia even obtains some forbidden make-up for the occasion and fantasises that “I’m going to get hold of a real woman’s frock from somewhere and wear it instead of these bloody trousers. I’ll wear silk stockings and high-heeled shoes! In this room I’m going to be a woman, not a Party comrade.”

The astonishing accuracy of Orwell’s vision, written way before a time that technology to facilitate government omniscience actually existed, has been discussed to death – but equally compelling are these subtler moments, where dissidents find seemingly small ways to rebel – instances of humanity in an otherwise grey world. The indulgent pleasures of coffee, sugar and sex, and the perhaps frivolous act of dressing up and putting on make-up become radical assertions of humanity, individuality and optimism. Just as elements of Orwell’s Big Brother seemed to play out in real life, there are also some interesting parallels with the way that dictatorships have put controls on dress, and the different ways citizens have sought to fight against it.

Control via clothing

Mussolini’s Italy (1918 -1939) offered its citizens very little choice in both their public and personal lives. Despite the French fashion for shorter skirts and red lips being in Vogue during the period, the Fascist state shut down as much foreign trend influence as possible, amping up a uniquely Italian aesthetic and pushing for a typically ‘Latin’ interpretation of beauty. Italian-made garments were preferred, with manufacturers previously inspired by the Parisian houses developing uniquely and exclusively Italian style. This gave citizens a strong sense of nationalist identity whilst simultaneously boosting home-grown manufacturing, in line with Mussolini’s goal for Italy to be financially and culturally independent.

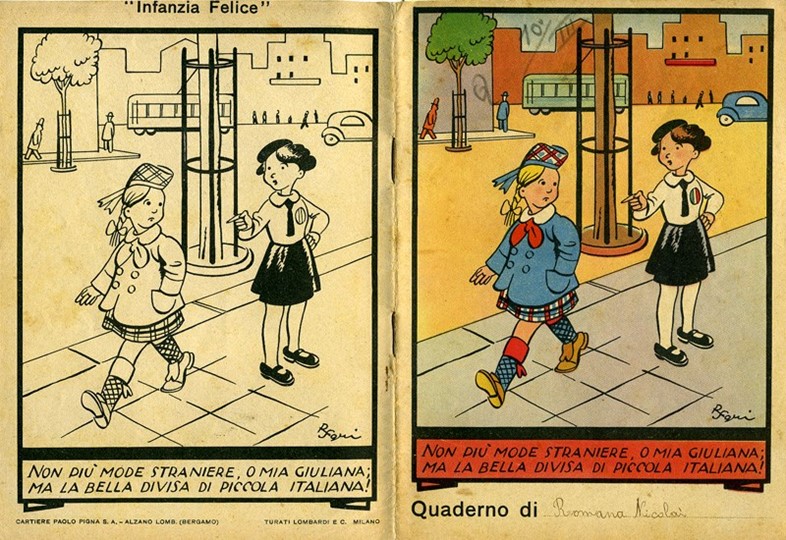

The sombre, make-up-free elegance of the regime’s Italian-made dress was designed to not just create an aesthetically uniform society, but to manipulate behaviour of its citizens. An essay published by weekly Magazine La Piccola Italiana, entitled 'Fashion under Dictatorship: Models of Education for Young Girls during the Fascist Era', explores the way that a youth magazine used comics to teach values such as not dressing up girlishly or being ‘vain’: “The Piccole Italiane were modest little girls as tradition expected them to be, at the same time as they had to serve the Fatherland and the regime as best as they could. In that way they became not only good girls but good Fascist girls: a double mission that, thanks to their garments, was meant to be discerned at first sight.”

Individuality via consumerism

In a free capitalist society where commerce is king, rebels opposed to the status quo have often sought to subvert or reject brands, from the crudely obvious warping and reapportion of Apple, Nike, and Coca Cola à la Banksy, to going full circle with the more nuanced “post aspirational” Normcore, which is, according to the New York trend-forecasting report K-Hole, about “realising that none of us are above the indignity of belonging.”

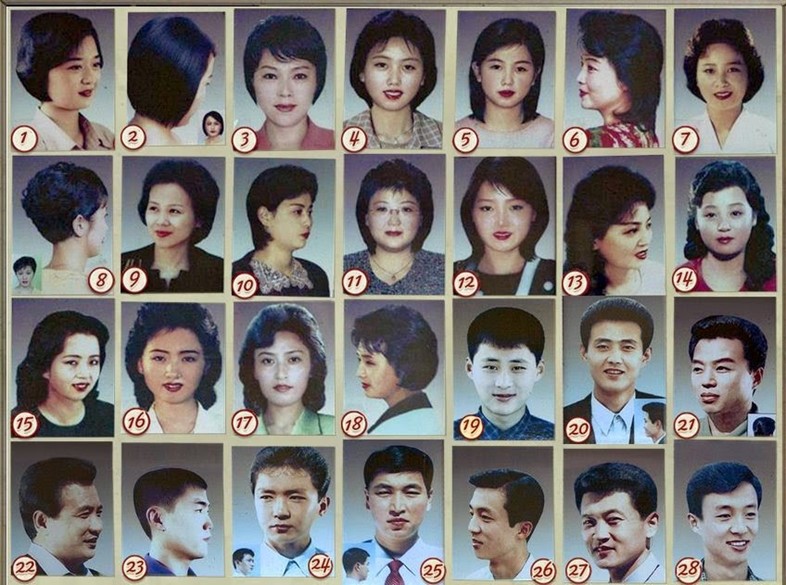

In a dictatorship like North Korea, where as recently as 2013 it was reported that citizens must choose from 18 state-sanctioned, no-nonsense haircuts, rebelling against the bland strictness of authority looks totally different. In a fashion feature for Dazed earlier this year, journalist Lu-Hai Liang spoke to a travel agent who specialises in tours of North Korea, who explained that North Koreans were extremely into brands, and he was asked by a local guide if he could source some foldable Ray-Bans for him. Lu Hai writes: “He added that this can lead to some overzealousness, citing an example of a Korean tour guide who wore shoes and trousers branded with the Apple logo.” What would look like consumer conformity almost anywhere else is rendered edgy and even revolutionary in the cut-off state.

Fashioning protest art

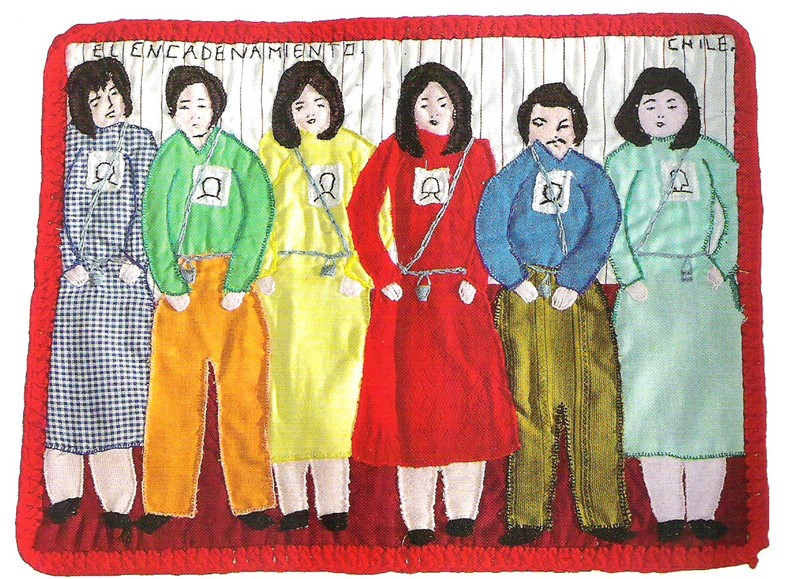

In Pinochet’s military rule in Chile during the 70s and 80s, the mothers, grandmothers, sisters and daughters of “disappeared” people sought to process their pain by creating folk-art tapestries embroidered onto sacks in groups. The colourful tapestries – arpilleras – depicted scenes from their repressed lives, and allowed them to tell their stories. Some showed scenes of protest – one piece displayed cloth dolls holding a banner that simply reads, “Where are the Disappeared?”; and others depicted scenes of prisoners in torture.

Too poor to buy cloth, the women used their clothes or the clothes of family members, which became especially poignant if they used items belonging to disappeared people. In the book Art Against Dictatorship: Making and Exporting Arpilleras Under Pinochet, Jacquline Adams writes: “With these raw materials and techniques, the arpilleras bore the stamp of the women’s poverty and gender… The aperillista’s gender shaped the arpilleras in that all the materials came from domains of life that were shantytown women’s responsibility: the home, the kitchen and the family.”