AnOther revives the living fantasy of the infamous surrealist artist

When outspoken art critic Jerry Saltz took aim at the art world’s lack of women artists included in collections, calling out MoMA for its embarrassing percentages of art by females, he imagined a scenario in which the museum could forget about their old master narrative of art history and, for a while, they could display a sign that read, "Pardon our appearance while we remove the stick from our asses, discard our atavistic linear idea of art, and lay out more of the whole story.”

One female artist who might appear in a more nuanced view of art history, would be Leonor Fini. Search for works by Fini on MoMA’s collections site – which boasts over 61,000 works online – and the only evidence of the accomplished surrealist painter is a portrait snapped of her by Henri Cartier-Bresson. Leonor Fini, born in Buenos Aires in 1907, was very much part of the Parisian surrealist set in the first half of the 20th Century. Growing up in Trieste, Italy, the wild young girl – whose hobbies included painting and scouring the Adriatic coast for bones and skulls – was expelled from three schools before embracing a less rigid lifestyle in Paris in the 1930s, where she slotted into the life of a bohemian artist with ease.

The surreal life

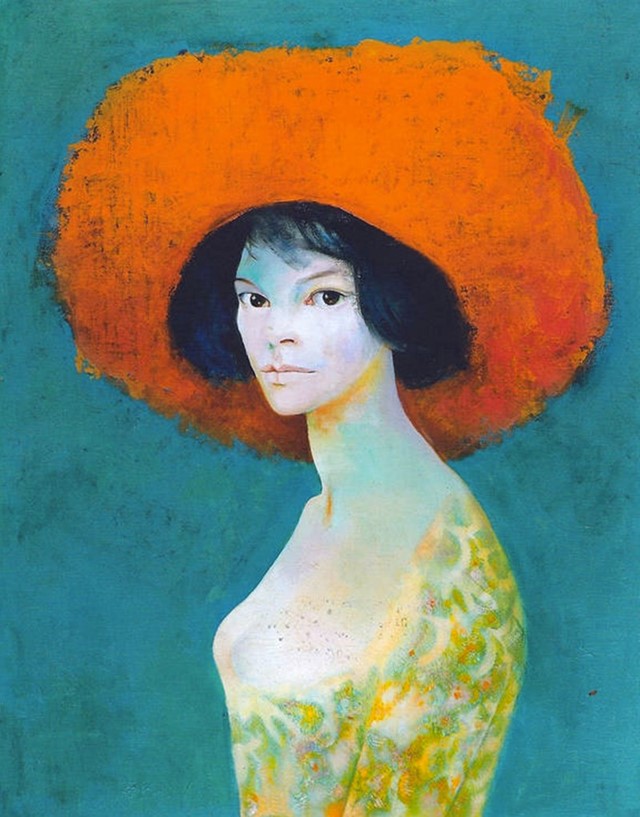

Jean Cocteau was enraptured by Leonor Fini’s “Réalisme irréel” and Paul Eluard, Jean Genet, Giorgio de Chirico and Max Ernst were amongst her first sponsors. Having charmed the art and fashion crowd, Fini had clothes custom made especially for her by the likes of Coco Chanel and Elsa Schiaparelli, and her first Parisian exhibition took place in a gallery run by Christian Dior before his move into fashion design. Fini painted fierce goddesses, priestesses, Ophelias, skeletons and highly symbolic hybrid creatures. She also painted portraits of her contemporaries, including writer Jean Genet, and is credited as being the first female artist to create a male nude. She earned the ultimate contrarian badge of honour – outraging the Daily Mail – when the paper described two of her mildly erotic works in the 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition in London as “a couple of slaps on the face of decency that should not be allowed to pass unnoticed.”

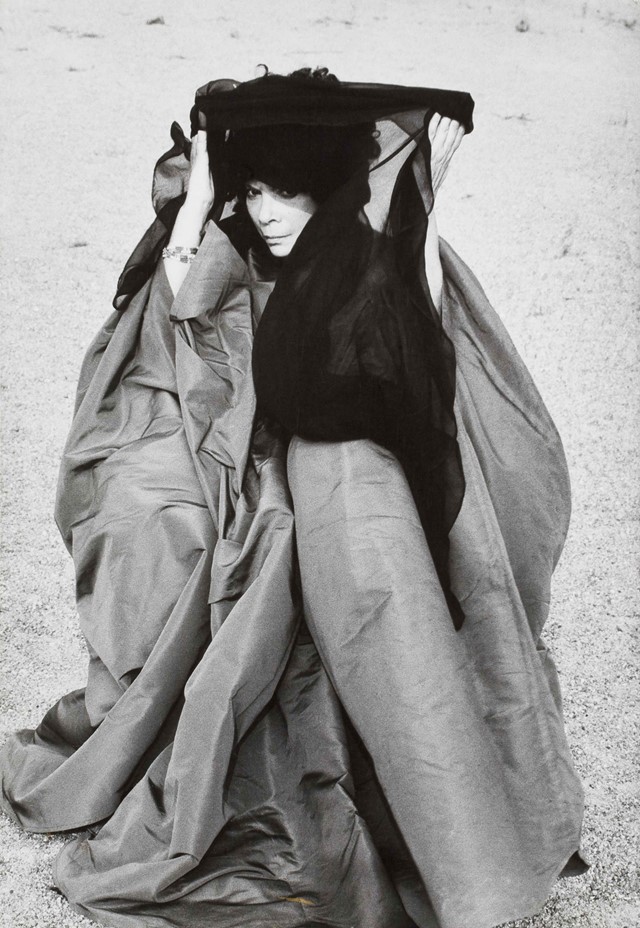

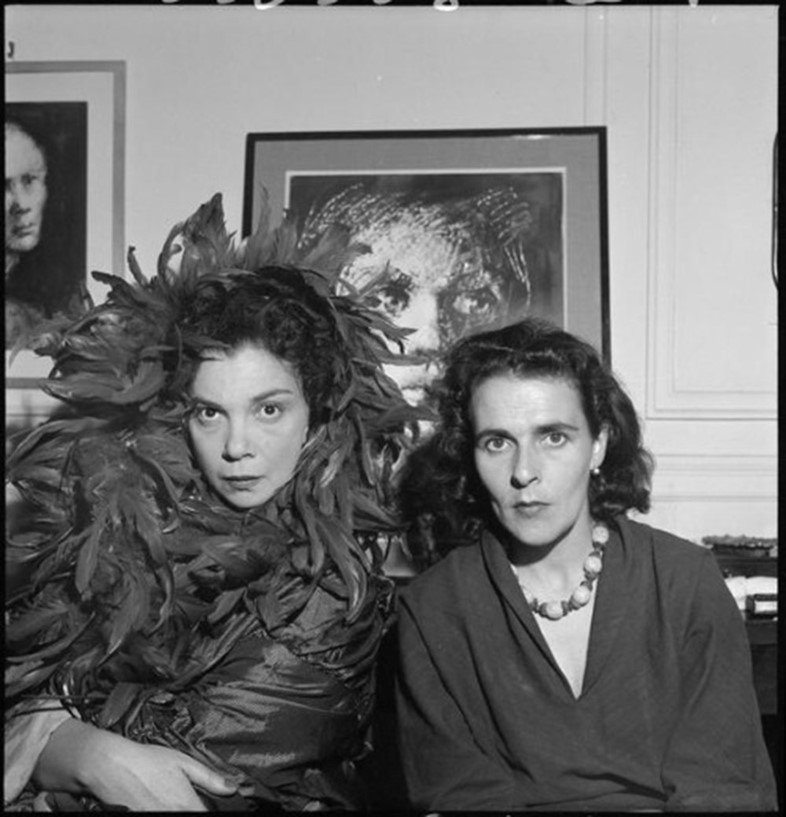

An embodiment of her work

Fini learned the power of disguise at an early age when, after her mother separated from her father and took her to live in Italy, the child avoided her father’s attempts to kidnap her by dressing as a boy. And she would continue to cross dress on occassion as an adult. Just as her painting depicted mythic-looking creatures, such as half animal half women hybrids, Fini also loved to transform herself. Later on in her career she would design ballet costumes, but at the height of her popularity, beloved by the bohemian Parisian party set, Fini was feted for her fantastical outfits, which comprised fur, feathers, masks and headdresses. Italian academic Ernestina Pellegrini wrote: “Some remember her dressed eccentrically, with a cat or lioness mask, and a feather wig. A painter of bizarre canvases with figures of metamorphic women, half angel and half skeleton, half plant and half animal, half Amazon and half statue – she incarnated the revolutionary ideal of independence and self invention. She was the incarnation – as Joycelyne Godard has suggested – of infinite realtà possibili.”

Called out by Jean Genet

Alongside his novels and poetry, writer Jean Genet mused his contemporaries in critical art essays; Picasso called Genet’s essay on Giacometti the greatest essay on an artist. Genet’s first critical art essay was on Fini, who produced sketches for a 1947 book of Genet’s poems as well as two portraits of the writer. Genet revelled in the grubby reality of life: sex, vagrancy and death were passionately romanticised by the writer. Although he appreciated Fini’s charms and talents, he was frustrated by the theatrics and fantasy in her work, and in 1950, wrote to her calling her out on her fantasies, and with crude psycho-analysis accused her of using the mask of costume to shield her from the realities of life.

He wrote: “If you hold so fast to the bridle of the fabulous and misshapen animal that breaks out in your work and perhaps in your person, it seems to me, Mademoiselle, that you are highly afraid of letting yourself be carried away by savagery. You go to the masked ball, masked with a cat's muzzle, but dressed like a Roman cardinal – you cling to appearances lest you be invaded by the rump of the sphinx and driven by wings and claws. Wise prudence: you seem on the brink of metamor-phosis (emphasis mine).”