We examine the lessons we can learn from the power, feminism and rage of the punk scene

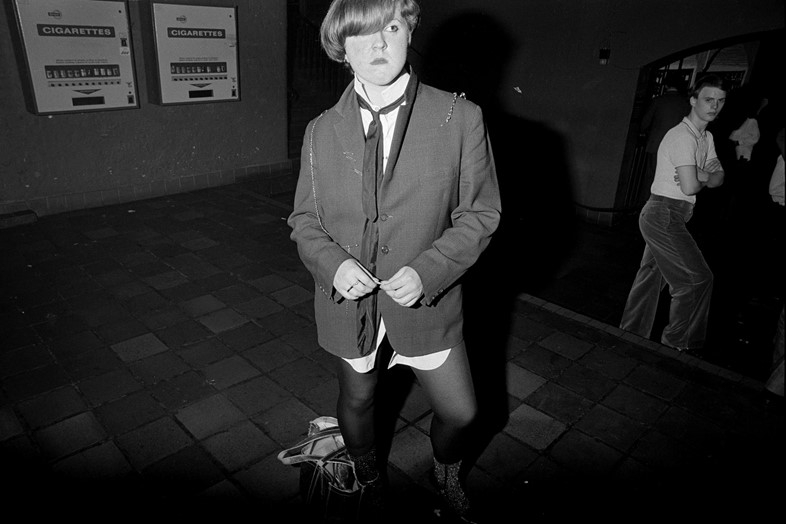

Karen Knorr and Olivier Richon determine the term punk as one which "designates without defining, a style and an attitude predicated upon disenchantment, nihilism, visual violence and theatricality". Shot between 1976 and 1977, their book PUNKS, published by GOST, is a brilliantly intimate exploration into the punk scene during a time of mass disenfranchisement and cultural revolution. Documenting the moment when The Sex Pistols were starting to play shows, the book explores a time when something new and revolutionary was offered to those suffering from economic and political disenfranchisement, a DIY alternative to the glam rock and consumerist culture than alienated so many.

In Zoe Street Howe's The Story of The Slits, Viv Albertine explains that when she saw the Pistols during her first year at Chelsea School Of Art – "That was it – it was like a light going on. It was the attitude more than the sound but it was like, my God, coming home at last. That was it... it changed everything." And it did; not only did the music change, and the clubs change, but so did the outfits that people wore. A new subculture emerged, one that embraced and celebrated difference and anger and shock value; a rebellion against everything and everyone. As Knorr and Richon declared, "The clubs were home for a nonchalant and declared narcissism", so here, we look at the lessons we can learn from their brilliant series.

Girls to the front

Punk was a time of Poly Styrene, The Slits, Palmolive, Siouxsie Sioux. It was a time during which women were reclaiming their identity and sexuality from that of the swinging sixties and, as Ari Up explains in Typical Girls?, "Punk really started with equality of girls. There's a whole culture – the first looks of so-called punk, so many girls contributed to that. And of course Vivienne Westwood, there was a window for female expression in punk when it started." Aggressively dismantling stereotypes around feminine docility, women in punk wore fishnets, bared their breasts and wrapped themselves in leather not to appeal to a patriarchal notion of sexuality but to reclaim it.

Any gender is a drag

As Patti Smith once said, "As far as I'm concerned, being any gender is a drag" – and deconstructing binary gender roles and liberating sartorial decisionmaking from them was a key part of punk's aesthetic. Women were free to adopt traditionally masculine roles on stage, in their lives and within their wardrobes; men were free to apply as much lipstick as they pleased and everyone looked far cooler for it. Putting into practice the tenets that later became the foundations of third wave feminism, punk promoted anarchy within the gender spectrum – both sartorially and politically – and lay the groundwork for the revolutionary feminism to follow.

Embrace (sartorial) bondage

"Oh Bondage Up Yours!" screamed Poly Styrene – and, while punk promoted freedom from the bondage of capitalism, it embraced it within its wardrobe. Worn for a combination of shock value and as a parodic commentary on the masochism of consumer culture, it confronted both prudishness and political apathy and has remained an emblem reappropriated by anyone from Rihanna to Beyonce looking to assert an aesthetic cool.

Get dirty

"Chaos is constructed and signified; it is not a state of raw nature but a sign of counter culture," explain Knorr and Richon. Spit, sweat and dirt were key visual elements, as punk fashion abhorred the pristine sterility and artificial facade of mainstream culture. Thus, by spitting on stage and embracing the tattered and the filthy, its ambassadors challenged norms and promoted exposure of the reality of the world and the bodies that inhabit it. It was Bakhtinian theory come to life; a brilliantly charged celebration of the carnivalesque, promoting the typically unglamorous elements of humanity.

Camaraderie is key

What perhaps gave punk such power, both visually and politically, was that it brought together a subculture of people who had previously been excluded from society. "Punks were young but did not like the cult of youth. Some were still at school, others were already out of work. Those who worked during the day were punk at night", declare Knorr and Richon – and its ultimate defining factor is its willingness to abolish categories of race, class and gender and become united under the principle that truly mattered: rebellion against the status quo. The similarities between working and middle class 70s disenfranchisement and current climes under a Conservative government are too obvious to analogise but, if we can learn anything from punk culture, it's the power of rallying together to protest – and that we can look brilliant while we do it.

PUNKS is out now, published by GOST.