The dust has settled on Phoebe Philo’s comeback – the first drop of her first collection has already pretty much sold out, and a second hit on Monday, both replenishing best-sellers and proposing new styles. In Philo’s own words – via the coldness of a press release – this label is “a seasonless, continuous body of work”. Which makes it an obvious point to look back, over the entire scope of her career – spanning her time at Chloé (alongside Stella McCartney from 1997-2001, and as creative director until January 2006), her tenure at Céline-with-an-accent (2008-2017) and her eponymous label, the first glimpse of which we saw in October – and get into the nitty-gritty of what actually defines Phoebe Philo.

She isn’t about a silhouette, like Christian Dior’s ‘New Look’, nor a specific garment, or system of dressing, like Gabrielle Chanel and her cardigan suits. Then again, those are old-fashioned fashions and Philo’s philosophy is nothing if not entirely modern. She does, however, have a distinct kinship with Chanel, who shaped and then reshaped her suits through her own lived experience – wearing her clothes and hence adapting them to her needs, and the projected needs of other women. You get exactly the same feeling with Philo, that her work fluctuates and shifts according to the demands of her life. As she matures, so does her work – the girlishness of her early work at Chloé, started in her twenties and with distinct nods at knowing ‘cool’, calming down into softer motherhood and then, at Céline, hardening, perhaps reflecting her own experience as a woman leading a major LVMH brand. Stereotype or not, most women would like to face up to their CEO in tailoring as opposed to a flirty summer dress, so Philo offered just that.

What does this latest change signify? An end of fashion, maybe – Philo is eschewing seasonal structures, titling her collections A1 (this one), A2 (due in spring) etc. That’s also a bit Chanel – very No. 5 – but possibly more significantly influenced by the fact that women who love her clothes everywhere have continued buying them after her departure from Céline, generating a voracious second-hand market only rivalled by the likes of Hermès Birkins and the limited-editions coveted by sneakerheads. And, in a sense, Philo’s label takes elements from both – the timelessness and quality of Hermès coupled with the frenetic hypebeast ‘drop’ culture of streetwear. In terms of style, however, the whole thing is purely Philo – as evinced by delving into her archives and pulling out a few prescient examples of her apparently fond remembrances of things past.

Masculine Tailoring

Women dressed in men’s clothing is even more of a cliché than wolves in lambs’ – but it’s something Philo arguably does better than anyone since Chanel. At Céline, one of her “eternal” pieces was a single-breasted man’s Crombie coat yanked so tight it sat double-breasted on the body; the other was the oversized trench coat, sometimes appearing so often entire collections would be remembered for it (read: Spring/Summer 2018, where they came doubled-up, looped together and even buttoned-on). Jackets throughout her tenure boasted sloped shoulders, seemingly cut for torsos far bigger and then cinched in, sleeves lapping hands to the knuckle, trousers slouching low, clutched to hips with a belt. There’s a paradoxical message of both strength and vulnerability in these pieces – emphatic hips hollowed out, pneumatic shapes lightened to allow bodies to move easily. Philo’s coats even lifted some of the construction techniques from menswear – her Crombie is interfaced in canvas, giving it a rigidity and armour-like security you rarely find in women’s clothing. Of course, the idea is present in her new iteration: a style is simply called the “Man’s Coat” – bringing those ideas together in one new garment.

Scarf Dressing

As an antidote to all that sharpness, Philo has often toyed with the idea of clothes apparently constructed from silk scarves – whether swathing volumes, or their pattern reconstituted on separates. Of course, her Spring/Summer 2011 Céline collection garnered plenty of attention for this, with graphic carré patterns worked over silk twill shirts and fluid trousers. But back at Chloé, in 2003, she made slithery satin dresses generously trimmed with fringe (in the same collection she also showed tufted coat that clearly echoed the hand-combed fringy megaliths she’s proposed for her own label, too). That collection was, Philo said, “A little bit of everything I love doing thrown in.” She also, it seems, enjoys confounding people who try to pigeonhole her as a minimalist obsessed with strict tailoring. Her bloused touches have often softened her savagely precise tailoring – her early collections at Céline toyed with the ladylike history of the house with prim blouses under navy pea-coating in melton wool. For her own label, scarf-like panels are attached to leather jackets and trench coats (more on those below) and form easy blouses and brief dresses.

Perfected Trousers

Rare is the designer studio across the world that does not have a pattern drafted from a pair of Philo-era Chloé trousers – based on 70s lines. She and McCartney worked with the late rock tailor Edward Sexton on their earliest suiting, both at Chloé and at McCartney’s own then-nascent label (launched post-graduation in 1996, and shuttered for the duo’s move to Paris). The silhouette, generally, is timeless – lean on the hips, often high-waisted, slim over thighs and kicking out subtly at the ankle to elongate and flatter. Philo’s cuts have been fetishised by ever-faithful throngs of women across her different labels – a bunch of different styles are proposed now. ‘High waist’, ‘flat front’ and ‘straight leg’ are terms often reiterated, emphasising that continuity and consistency of Philo’s fit. Again, it’s about shirking off fashion, arguably, in favour of style. Many of them have sold out – to both fans and, probably, rival designers.

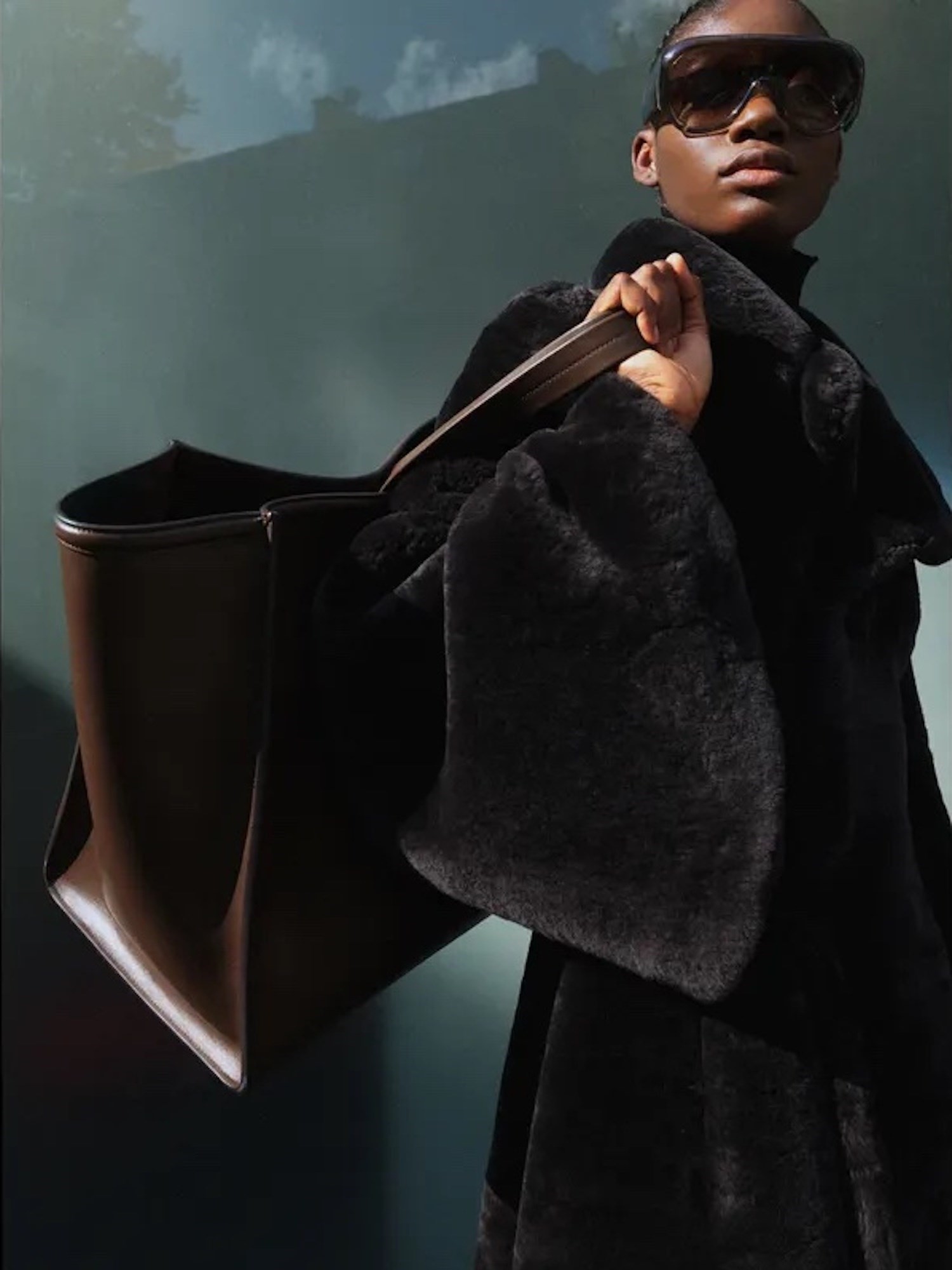

Big Bags

Practicality is one of Philo’s fundamental considerations. And nothing is more practical than a big old sack of a handbag to drag around your worldly goods. It’s something every woman – and many men – need on a daily basis. Philo has never designed ditsy, bitsy bags. The first break-out It Bag success she proposed was the Paddington, a hefty hold-all with a leather-trussed padlock that made Chloé a mint in 2005 (the first 8,000 sold out immediately). It also did away, swiftly, with the armpit-crushed micro-bags like the Saddle, the Pochette and the Fendi bag-bakery of Baguettes and Croissants that spawned them all in the late 90s. When Philo did smaller bags, she rendered them Tardis-like – her Céline ‘Trio’ has three zipped pockets to allow you to stuff the pillowy leather oblong with belongings. There she also proposed two other, capacious styles the “Luggage” – possibly so-called due to its expansive horizontal size like an early 20th-century travelling bag, or indeed the amount you could “lug” in its volume. She also offered a simple leather tote, now a standard proposition from fashion houses but then a minimal anomaly shorn of clunky hardware and branding, a literal sack of leather.

These seem like simple gestures but there’s meaning in not reducing women to clutching belongings in tiny envelopes – the earliest handbags in the 18th century were called “reticules” and were dubbed “ridicules” by social satirists – male, of course – who criticised women for overstuffing them. Fitting. For her own label, most of Philo’s bags are big – including, obviously enough, one named the XL, a giant tote almost 60cm wide, into which a working mother like Philo could fit anything, including a small child and, feasibly, an apocryphal kitchen sink in need of re-plumbing. As Sarah Mower once wrote – much better than I – for American Vogue: “It’s the work of a woman working for women, who simply gets it.”

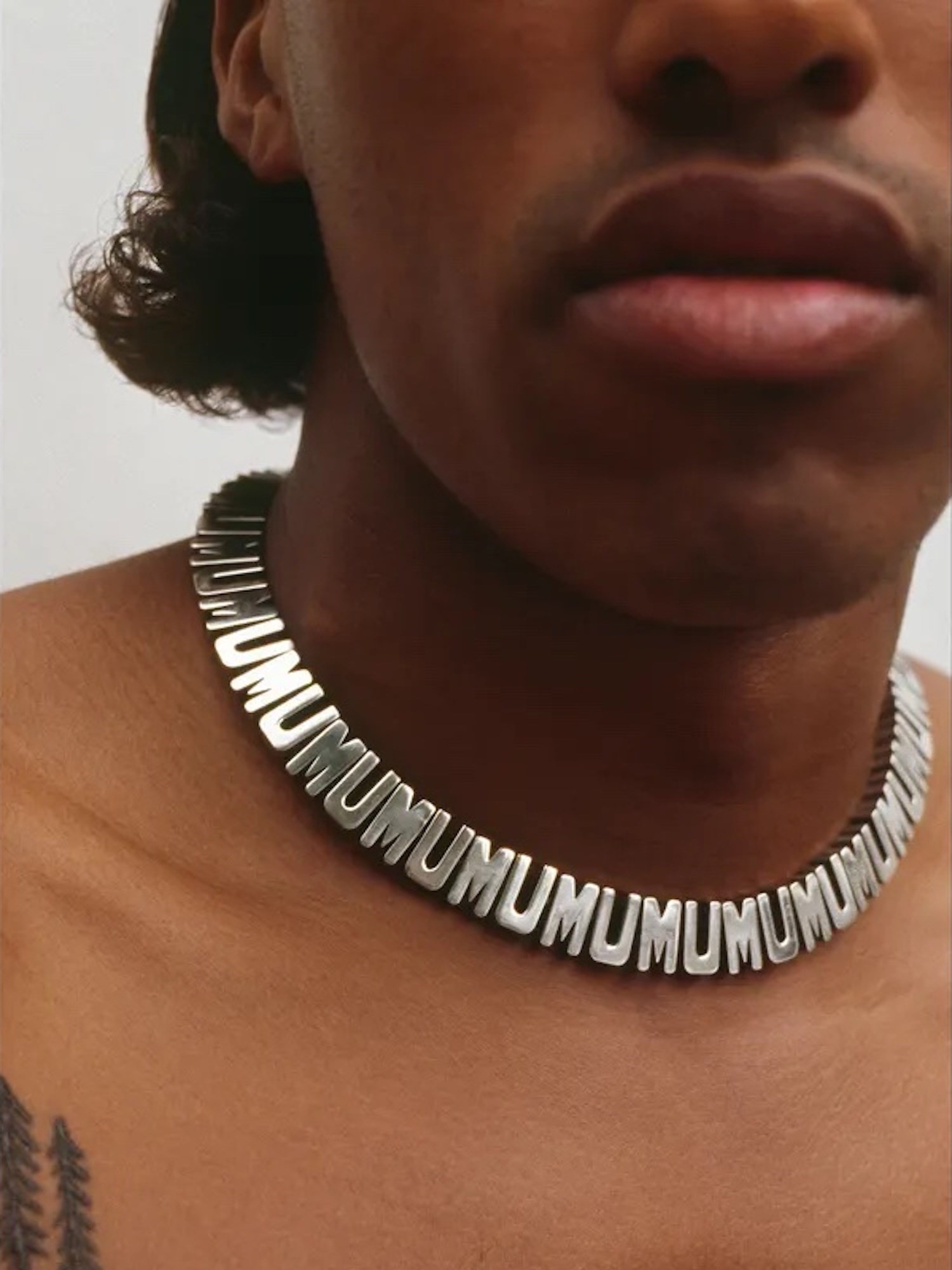

Dodgy Jewellery

Philo’s love of statement jewellery is an unpredictable offshoot of her otherwise faultless taste: there’s something intentionally dodgy about many of her jewellery offerings, including her sell-out “MUM” necklace, whose genealogy in the catalogue pages of UK high-street stalwart H Samuel has been much-discussed on social media, if perhaps not in the mainstream press. But Philo has always mixed high with low, the refined with the kitschy bad taste – which, as Diana Vreeland once pronounced, is far better than no taste. At Chloé, Philo and McCartney showed intentionally tacky gold chain necklaces, while one of the best-selling jewellery items from her Céline tenure was an alphabet of bamboo-shaped letters that, in any other context, would have languished in the discount bin.

Short Shorts

These, admittedly are an outlier – hardly a staple, but with an interesting back-story. Philo’s aesthetic lineage traces back further than her career as a named creative director – in 1997, she was the vital right-hand woman to Stella McCartney in their spectacular revival of the then-ailing French fashion house Chloé – “No hierarchy malarkey,” Philo told Amy Spindler in the New York Times at the time. She would in turn become its creative director in 2001. For Spring/Summer 2000, McCartney and Philo created a western-tinged show of frayed denim, chopped-up T-shirts and blingy gold chains, which would prove enormously influential. And these studded gold micro-shorts in Philo’s latest drop – a look-at-me style already doubtless being ripped off by the mass-market churn merchants as we speak – are obvious descendants from the buttock-baring Chloé originals. They’re not what you might call a Phoebe Philo signature – but they do demonstrate the eternal unpredictability of her design Philo-sophy, the reason why we’re all on tenterhooks, and crashing her site whenever a new drop comes along.