Back in 1981, a 15-year-old Andre Walker sat in his bedroom in Brooklyn, New York. With cut-outs from his mother’s magazines plastered all over the walls – “like a Yayoi Kusama installation”, he says – he dreamt of working as a fashion designer, despite having little more experience than taking a pair of scissors to a T-shirt and selling it at his mother’s hair salon.

That same year, he launched his debut collection at a neighbourhood nightclub, Oasis, capturing attention with intricately cut coats that had been designed freehand, without traditional patterns. It was his first step towards fulfilling his ambition of following the path forged by Black New York-based designers Stephen Burrows and Willi Smith, whose WilliWear label Walker later worked for.

Walker is today regarded as one of fashion’s cult figures, widely adored but rarely celebrated in the mainstream. He is best known now for his recent work with the likes of Marc Jacobs, Kim Jones and Comme des Garçons’ Rei Kawakubo. However, it’s his signature flat cut and avant-garde silhouettes, collected and treasured by fashion fanatics such as Patricia Field, that are truly impressive – more so, when you consider he is entirely self-taught.

More than 30 years on since that first show of Walker’s, Grace Wales Bonner made her own design debut in London, drawing on her British-Jamaican background and restarting a conversation initiated by the Black designers that came before her. So few that you could count them on a single hand, they include Burrows and Smith, Patrick Kelly, and of course, Walker himself.

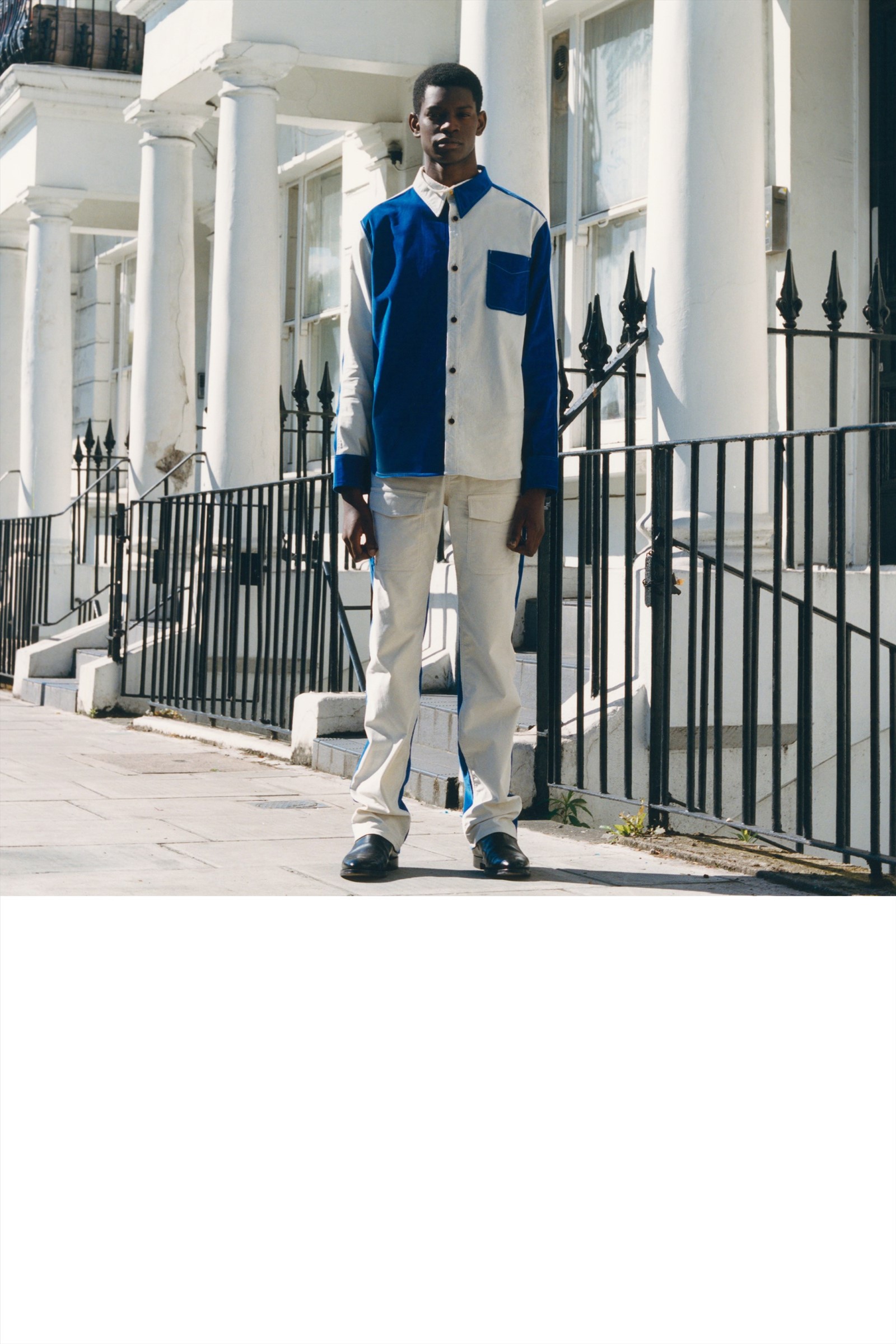

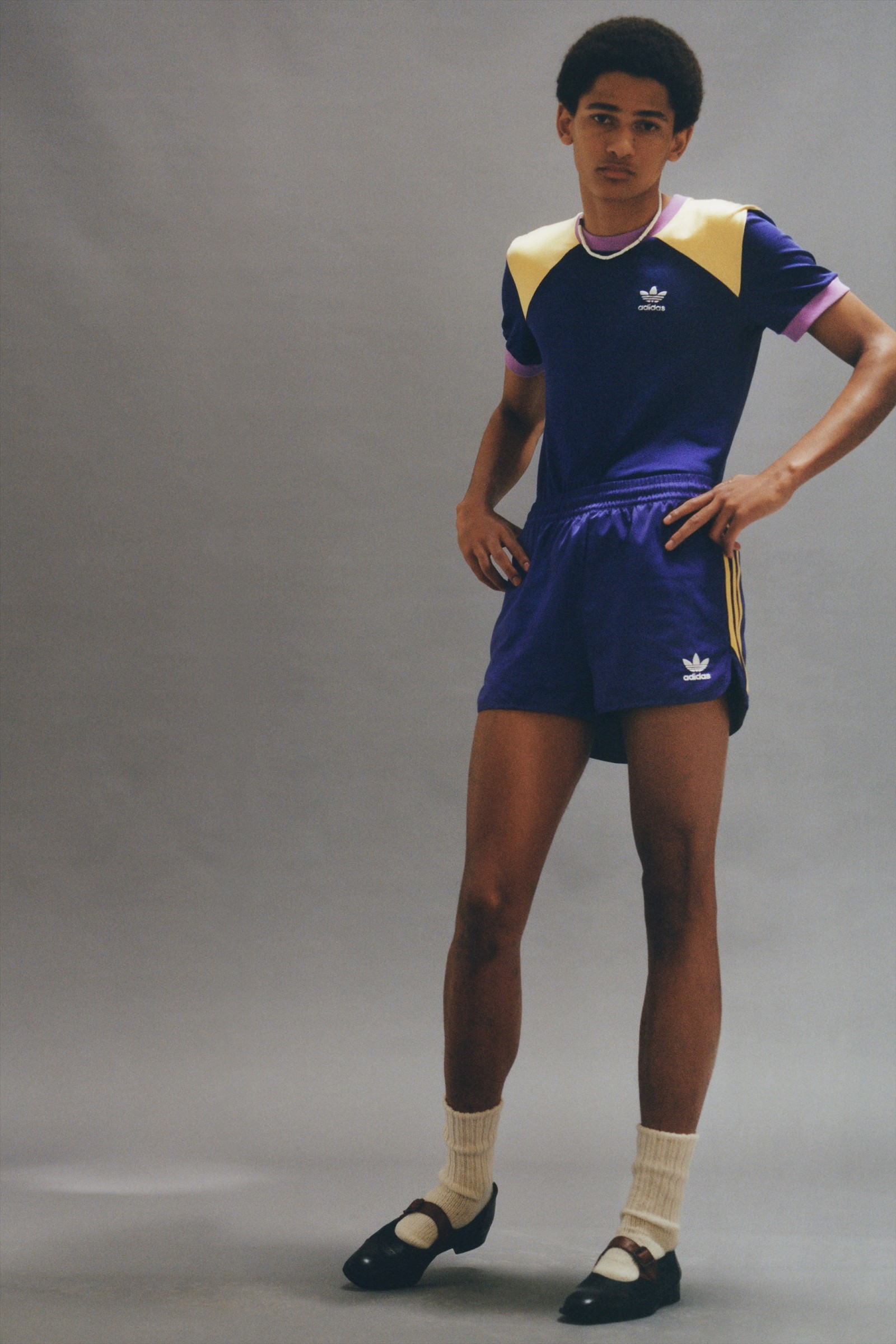

Inspired in large part by her own heritage, Wales Bonner has gained renown for her considered repertoire that reimagines Black masculinity from a softer, more sensual viewpoint, connecting the past and present and offering impeccable tailoring with craft details that make the pieces feel like treasures – Sunday best.

But Wales Bonner’s focus extends much further than her own roots, meandering through Cuba, India, and Senegal, too – in thoughtful appreciation rather than appropriation though. Her collaborators are equally global, comprising the Nigerian writer Ben Okri, Ghanaian-Russian photographer Liz Johnson Artur, African-American artist Jacob Lawrence and many more.

Connecting across the Atlantic, the pair muse here on their respective careers and fashion’s complex relationship with race.

Zoom conversation between Andre Walker and Grace Wales Bonner, August 2020.

Grace Wales Bonner: I wanted to start by asking you about your show in Paris a few years ago.

Andre Walker: That was Non Existent Patterns [Spring/Summer 2018]. What was cool about that show was that it came a year after my father died, when I was losing my mind and having an existential crisis. But then lots of people started sending me clothes that I’d designed when I was a kid – maybe 16 or 17 – and I thought it was amazing that those clothes had initially been made without patterns. Lots of the clothes were cut freehand, that’s how desperate I was to participate in fashion. I remember thinking, “I have to be a designer.” So, showing the collection in Paris, my teenage work, as an adult approaching a midlife crisis, was amazing. It was a gift from God. I really believe that was my father’s send-off. He was saying, “Please take care of him.”

GWB: It was so incredible and spectacular. It was just unbelievable how beautiful and timeless it was. In a way, it’s kind of shocking to see something like that because that’s not what we’re used to seeing in fashion at all. Do you think it’s possible to create in that way within the framework that currently exists in the industry?

AW: Oh, totally. Even more so now than ever. I believe these times will bring about the most important strongholds that will keep fashion going, because it’s a utility like soap. Intensity is just as necessary as simplicity and lucidity. The truth is that we only have this world to work on, so even with climate change, social injustices and a pandemic, it doesn’t change the fact that the economic model is still in place and we will always have to work. Trying to inject some kind of joy into what we’re doing is key, although passion can be very draining. I’ve been drained out, but I’ve also been lucky, I guess. Sometimes my passion overtakes my ability for reason and logic, but it’s up to you how sensitive you are about your business. If ten people say it’s wonderful but one person says it’s crap, you have to be able to look at what you’re doing, how you’re communicating your message, and take it from there.

GWB: I was so excited to first discover you and I’ve always really admired you. I’m so inspired by your work and it’s been incredibly influential on me and my friends – people like Tom Guinness, Mavi [Staiano] and Eric N Mack.

AW: I love you guys so much, you’re my lifeline.

GWB: I feel like you have really managed to protect your freedom over time and it’s inspiring to see how you create and how [your work is] completely in its own space. That’s so important, having space to work and operate in that way. How do you keep it sacred?

AW: The protection you talk about isn’t really protection, it’s more of a habit, but it can be protection, too. It’s a lot of intuition, observation and analysis, sometimes with a bit too much overthinking, too. If you can balance overthinking with a bit of spontaneity and a lot of impetuousness, then you’ll get what you love about me. I’m also a highly competitive person and an impossible elitist. I’m sure whenever my name is brought up in conversation, people say, “He’s impossible” – and I am impossible. I thought I had to look at 400 collections a year just to know what I didn’t want to do, but now it’s up to 10,000 collections a year. There’s so much stuff out there you could drive yourself insane just by looking around. It’s so stressful out there right now, especially for me – I grew up not having a phone or emails in my pocket, and that is real freedom. Freedom for me is also teaming up with people I can actually work with and [with whom it can] be mutually beneficial. Every designer has something different to share, whether it’s culture, process or provenance.

GWB: For me, I’m interested in a kind of sensitivity, sensuality or softness and allowing myself to express myself through that. It’s often in connection with the way I think about luxury as well. I look for a European luxury and these heritage brands, and then create something that comes from a different cultural perspective that celebrates or values the same ideas of beauty and craft. It’s about hybridity, a meeting point between the two things.

AW: You’ve done a great job of bringing the cultures you’re interested in into the story, it always feels like a discovery. You have a National Geographic approach to things – it’s about discovery, viewing what is out there and what exists without judgment, rather than feeling like you’re being hit over the head with some kind of blatant ideology. That’s how I think of what Yves Saint Laurent did. I didn’t really appreciate what he did until maybe ten years ago – I used to think it was pure appropriation. What he actually did is get these great caricatures and it’s wonderful. He introduced people to different cultures through his work.

“If you can balance overthinking with a bit of spontaneity and a lot of impetuousness, then you’ll get what you love about me. I’m also a highly competitive person and an impossible elitist. I’m sure whenever my name is brought up in conversation, people say, ‘He’s impossible’ – and I am impossible” – Andre Walker

GWB: I’m interested in beauty and connecting that through time – that’s one guiding principle for me. My work also connects to identity and representing identity, but it’s more about revealing something that is timeless or something that has always been there but hasn’t always been represented or shown in a nuanced way in fashion. That’s what I thought anyway, when I first started thinking about male representation. There are different strands to it, but I believe that beauty can seduce you into an ideology, so it has a role to play in enticing people into a story.

AW: The word nuance is interesting because that’s what fashion is all about. Fashion is about appropriation. All of this screaming about cultural appropriation and that blonde girls can’t have cornrows or Black women can’t have blonde hair – it’s totally ridiculous where I come from. Nuance is so important and this is the perfect moment to use the plasticity of this time to our advantage and reshape the narrative towards something more beneficial than entirely racial.

I love the idea of walking into LVMH and seeing lots of coloured people – by that, I mean different races – yet I love the idea of being surrounded by people who are really great at what they do, even more so than different races. That’s just my personal experience. I’m always looking for the best colours, or the best way to explain myself. It’s a continual search for the best of everything.

GWB: In terms of broadening the spectrum in fashion – which is what I was interested in when I first started out in 2014, 2015 – I think things have changed considerably since then. Things have been evolving and there’s a broader representation within fashion [now]. Compared to my initial starting point, the context has changed, but it’s a constantly evolving landscape.

“I’m interested in beauty and connecting that through time – that’s one guiding principle for me. My work also connects to identity, but it’s more about revealing something that is timeless or something that has always been there but hasn’t always been represented in a nuanced way in fashion. I believe that beauty can seduce you into an ideology, so it has a role to play in enticing people into a story” – Grace Wales Bonner

AW: I’ve never thought about race, unless I was being treated badly by somebody who was unfortunately inclined. When it comes to clothing and fashion, they’re utilities to me, so I never thought about race when it came to design. I grew up in a time when there were designers such as Yves Saint Laurent, [Hubert de] Givenchy, Claude Montana and Thierry Mugler – who were all making use of Black, Asian, Indian and lots of different models. There were also people like Willi Smith and Stephen Burrows. When I think about designers, I don’t think about race, I think about what is good – I refuse to be distracted by things such as race. Looking at the past is one thing and it can be helpful, because it clearly helps outline and identify inequality and injustice, which is great, but we can’t continue to live in the logic of unforgiveness forever. I’ve struggled with that for a while, but it doesn’t work in life or in fashion.

GWB: Something I think about is just having the space to develop things in a playful way. I do feel like I need to protect or shield myself so I can have a little bit of room. The world in some way, especially in terms of narratives, can be framed differently or taken somewhere else, but ultimately it’s personal expression. It should be more about having the space to create freely.

AW: It’s a very strange time we’re living in right now. We just have to watch what we’re actually believing and thinking and not just take things for granted. I don’t like the idea of being dragged into something or put in a box – designers, artists and creators are meant to be free.

GWB: That’s something that I really admire when I see your work, and it’s something that can’t be traced. Everything you’ve talked about in the sense of what you value and it not being pinned down is really powerful.

AW: That’s how I feel about your work, too, and I loved your last collection, by the way. You’ve done a great job at establishing yourself and you’re still a young girl – I’m twice your age. So kudos to you and kudos to me. I should be dead by now because of my ridiculous lifestyle, but it’s a total blessing to be here still.

I’ll send you my phone number so you can text me whenever you get freaked out. I’ll send you something ridiculous and make you laugh and you’ll think, “OK, I’ve got this.” With everything that’s taken place in my life, I would say keep going. You’ve established yourself so beautifully that you can just keep going, going, going – don’t be afraid.

GWB: For me, the goal is really to have the resources to create everything I imagine, and I hope for the same for younger generations, too. I hope that they will have access to the resources necessary to create at a certain level and will be ambitious with that. I hope that even older ideas of beauty will be celebrated, and that older and newer ones both have a place in the future.

AW: I’d like to have a place as well – I don’t stop looking for work. What I hope for fashion, though, is that people really start to review themselves. They can be so enamoured with the history and ideals of fashion that it can become stale. Fashion is sometimes so fleeting, too, so I really like the idea of having something to hold on to, like a treasure, instead of throwing stuff away. How can we get it to be more logical, practical, reasonable and sustainable? Those are my goals and that’s why I’m still working. If I were to express my personal wish, I’d say that I want to be immersed in what I do best and have the opportunity to do it. I won’t give up until I’m in a coffin – my dreams are endless. I dream of being the head of Hermès and I will never, ever stop.

This story appears in AnOther Magazine Autumn/Winter 2020, which is now on sale internationally.