Using discarded pattern paper, fabric samples and other objects found in her studio, Marie Valognes’ constructions capture ROBERTS | WOOD’s A/W18 collection in a whole new light

There has a been a growing tendency among young designers to do away with the traditional runway show completely. Whether choosing impressively realised presentations, intimate showings for editors behind closed doors or one-off printed publications as alternative ways to communicate their work, it is an approach both imaginative and pragmatic.

Nottingham-born, London-based Katie Roberts-Wood is one such designer. For her latest collection under eponymous label ROBERTS | WOOD, Autumn/Winter 2018, she called upon three image-makers, in lieu of a show, to interpret her clothing in a way entirely of their choosing: Bex Day, a photographer, undertook a live photoshoot; the collective Crown and Owls imagined an immersive, multi-sensory “world”; and Marie Valognes, known for her whimsical approach to sculpture under the pseudonym ‘mise en’, created pieces inspired by Roberts-Woods’ approach to the creative process.

“For a while now we’ve been experimenting with different things, whether it’s an installation, or presentations, or catwalk shows before that,” Roberts-Wood tells AnOther. “Getting into that trap of a standard way of showing doesn’t really interest me – I’d rather push trying different things. I think it can feel quite restricting if you get into this cycle of having to show in a certain way every season.”

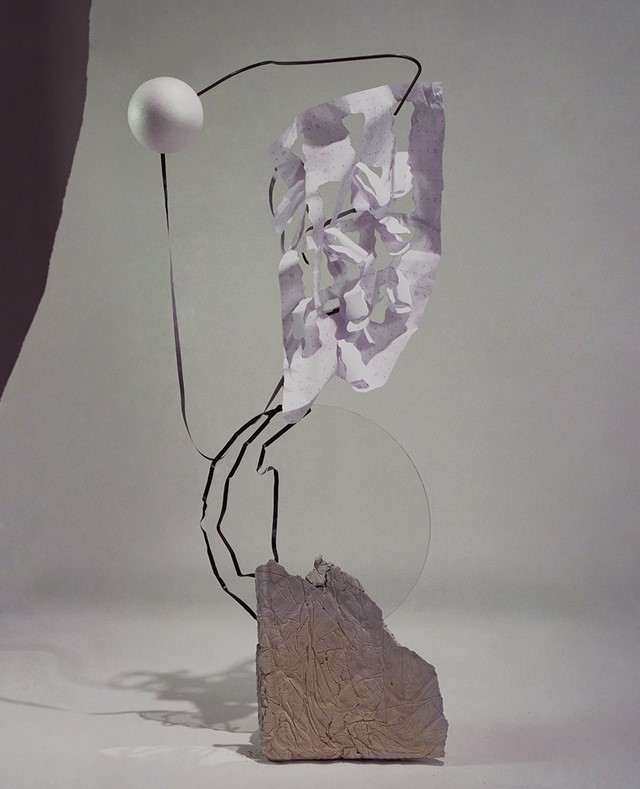

Perhaps the most interesting – or at least obscure, in that the final images do not feature a single garment – are the sculptures by Valognes, who Roberts-Wood discovered via Instagram. Valognes’ pieces – which often use disparate items (previous creations have used a Turkish sausage, marker pens, vegetables, plastic bags and toilet paper, among other things) – are idiosyncratic interpretations of what she sees around her.

Often, her sculptures find their starting point in looks from fashion shows – Valognes created such a series for AnOther – where the marabou trim of a Prada outfit might be made from hay, or the ruffles of a Molly Goddard gown are evoked in the undone blue netting of a shower poof. Her work delights in the freedom of pure association. “I tend to make visual connections when looking at forms,” she previously told AnOther. “They sort of bounce off each other.”

Here, though, Valognes took an altogether more abstract approach – invited into the ROBERTS | WOOD studio, she was fascinated not with the final garments but the oftentimes intricate processes behind them. There, she and and Roberts-Wood found common ground – the latter, who studied medicine for ten years before undertaking an MA at London’s Royal College of Art, relishes in an experimental, trial-and-error approach (her graduate collection was made with the challenge that it should not contain a single seam). “I don’t tend to start out with a theme or a moodboard or anything,” Roberts-Wood says. “I think part of that is my background – I wasn’t actually trained in design, so I feel like I missed out on that ‘the way you’re supposed to put a collection together’ thing.”

The result is a series of sculptures that become a portrait of a designer’s creative process. Pleats of fabric, crumpled pieces of pattern paper or folds of tulle are delicately balanced on polystyrene balls or shards of concrete to become visualisations of Roberts-Wood’s mind, and studio, at work. “I feel like it took a bit of a life of its own which is what I was hoping for; I was hoping people would run with it,” Roberts-Wood says. “I think she certainly recognised the really important things in the process about like making and the experimentation but visually took it in her own direction, and presented them in this really different way.”

The A/W18 collection itself, which Roberts-Wood and her team are currently finishing the production run for, for stores that include London’s Dover Street Market, became a study in the subversive power of cuteness. The designer was initially delighted by iridescent fabrics she found, which reminded of the surreal colours found in nature (“we call one the jellyfish dress,” she says). “I was really interested in the idea, especially with using ruffles and bows and things, of these traditionally cute emblems as a protective, evolutionary mechanism – how it can be an advantage either in nature or in life.”

In fact, the title of the collection, Kinderschema, came directly from this phenomenon. “It’s like the set of characteristics that you might find in a baby animal, like a puppy. They have this set of features, like really big eyes or big ears, and it’s actually a mechanism that they’re using to make sure they’re protected,” she says. “I just like this idea that it’s slightly… manipulative.”