Arte Povera brought the political upheavals of the 1960s into Italy’s genteel galleries – now, a new generation of fashion designers is drawing on the movement’s DIY spirit

Marking a major shift from the previous season’s geometric draping, Rick Owens’ A/W18 show saw models wearing tentacles of padded fabric that seemed ready to swallow them whole, tied together with an eerie palette of dark greys and silvers. In an unlikely reference point for a designer best known for his playful deconstruction and luxurious technical fabrics, Owens’ primary inspiration was the group of Italian artists united under the umbrella of Arte Povera, a gang of radical creators more likely to work with materials found on the street or in dumpsters than put brush to canvas.

Translating as ‘poor art’ (referring to the lowly status of the materials rather than the artists or their audience), Arte Povera now stands as one of the 20th century’s most quietly influential movements, anticipating everything from the flourishing of conceptual art in the 1970s to the studied banality of 1990s fashion designers. At a time when Italian design was characterised by colourful, graphic fluidity and the art world was in thrall to the sleek rationality of American minimalism, Arte Povera represented a dramatic breakaway from the cultural status quo.

Using everyday materials from coal to dried leaves, burlap sacks to neon, this loose artistic fraternity brought the class struggles of the period into the sanitised, genteel world of the whitewashed art gallery and by doing so, fiercely asserted their central belief that people from all social strata could create and engage with the elitist cosmos of high art. Across five key moments in the movement’s progression, we consider the influence held by Arte Povera in the worlds of art, fashion and beyond.

1. It was a response to a period of great political upheaval

The 1960s are remembered as one of Italy’s most tumultuous periods, as growing dissatisfaction with the country’s coalition government led to a widespread outbreak of civil unrest in 1969, now known as the ‘Hot Autumn’. As the political landscape became increasingly polarised, the artists grouped together by Germano Celant – the critic responsible both for coining the name of the movement and developing its first manifesto – hoped to bridge this divide by uniting all classes of society with their pragmatic, accessible vision of a new kind of social art.

From the very beginning, Celant noted an “undeniable” reciprocity between politics and Arte Povera: taking found materials and refashioning them as works of art was an attempt to break down the borders between daily life and the previously detached realm of high art. Celant’s manifesto purposefully nodded to the rhetoric of Communist political uprisings from China to Argentina, while works like Luciano Fabro’s Italia Rovesciata saw a sculpture of the Italian peninsula hanging upside-down and Jannis Kounellis’ Senza Titolo (Libertà o Morte) directly referenced key figures from the French Revolution such as Marat and Robespierre. For Celant, creativity was no longer the preserve of the wealthy or educated – anybody with a political voice could sign themselves up to this groundbreaking creative moment.

2. The movement was embedded in the traditions of Italian art history

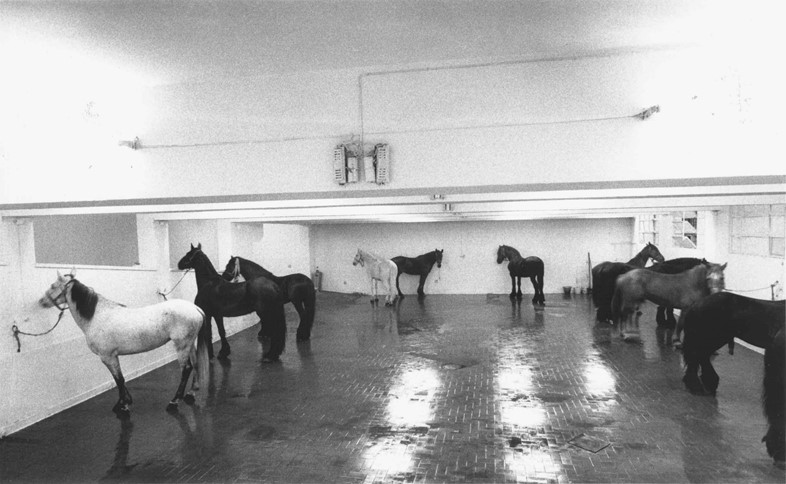

For all its iconoclasm, Arte Povera was always in dialogue with art and architecture from centuries past. Jannis Kounellis’ infamous 1969 installation Senza Titolo (12 Cavalli), first exhibited at the L’Attico Gallery in Rome and consisting of 12 live horses tethered to the gallery walls, spoke to the grand art historical tradition of the equestrian portrait that can be traced all the way back to the iconic statue of Marcus Aurelius in Michelangelo’s Piazza del Campidoglio at the top of the Capitoline Hill – here, Kounellis injects this iconic image of masculine military arrogance with a dose of wry humour.

Another key artist from the period, Mario Merz, took the neon strip lighting more likely to be found in the seedy bars and brothels of the Italian urban sprawl and used them to illuminate galleries in Rome and Milan’s most well-heeled neighbourhoods. A famous series by Merz uses neon to dictate the Fibonnaci sequence – a nod, perhaps, to the invisible rules and ratios of geometry, derived from organic patterns, that underpin the greatest works of the Italian Renaissance. Despite the lowliness of its materials, arte povera always linked back to its home country’s rich cultural and intellectual heritage.

3. Italy’s currents of artistic change spread all the way to America

Arte Povera emerged during a period when American art was dominated by artists like Donald Judd and Frank Stella, who prioritised experience and participation over the deeply personal (or as they would put it, egocentric) work of their predecessors, the Abstract Expressionists. Using industrial materials and geometric shapes to articulate spaces for the human body to interact with, the coldly impersonal work of the Minimalists was a world away from the politically charged, rough-and-ready sculptures of their Italian contemporaries.

The beginning of the 1970s, however, saw a marked shift in the American artistic consciousness, as land artists like Robert Smithson and Michael Heizer (another creator noted by Rick Owens as an influence on his collection) disavowed the Minimalist detachment from landscape and began making large-scale sculptural installations using natural materials. The rational, functional forms of the previous generation gave way to a newfound interest in myth, magic and mysticism – all key interests of the Povera artists, who looked to the hidden stories within even the most quotidian of objects.

4. The DIY spirit of the movement has been seen in fashion before

Rick Owens isn’t the first fashion designer to tip his hat to Arte Povera’s boldly egalitarian worldview. In 1991, Spanish designer Miguel Adrover arrived in New York and began showing his collections of spliced knock-off Louis Vuitton bags, distressed I Heart NY T-shirts and Burberry trenches refashioned as dresses. Despite fizzling out after a series of financial blunders, Adrover’s anarchic use of ready-made designs in the context of high fashion – and vocal dislike of the rampant consumerism of the 1990s – mark him out as one of fashion’s greatest heirs to Celant’s worldview.

Of course, no mention of the transgression between high and low in fashion could go without mentioning Martin Margiela. At the end of the 1980s, when designers like Thierry Mugler and Claude Montana dominated womens’ wardrobes with their sleek power-dressing, Margiela threw out the stilettos and sent models down the runway in garments that were ripped, frayed and falling apart. As with the artists of Arte Povera, Margiela understood that context is everything: his infamous S/S90 collection was shown in a tent out in the suburbs of Paris, with the locals sitting cross-legged on the front row, marking a seismic shift in fashion’s previously stringent definitions of how high fashion should and could be shown.

5. Rick Owens’ revival of the Povera spirit is surprisingly relevant

Looking more closely at the collection, Owens’ tip of the hat to Arte Povera becomes clearer. Pilled grey fabrics resemble the movement’s fondness for insulation materials and fibreglass, while the details of nylon safety buckles and metal studs that recall construction bolts point to the inside-out, industrial quality of Jannis Kounellis’ rickety assemblages. So too do the roughly hewn shapes and weathered, organic materials of Arte Povera’s best-known sculptures carry echoes of the prehistoric or the elemental – much like the intuitive, hand-crafted approach of Owens’ approach to form that has become his signature.

While the movement’s anarchic beginnings may be diluted as it becomes absorbed into the world of fashion, with Owens’ garments going on to be sold in some of the world’s most exclusive department stores and boutiques, it’s worth remembering that pieces from the Arte Povera generation now also reach eye-watering prices at auction. A more compelling explanation for why it feels relevant in 2018, perhaps, is its distinctive understanding of the relationship between art and activism. Arte Povera’s resourceful and inclusive spirit serves as a reminder of the political potential of design, and that everybody has the power to create regardless of the resources you have to hand.