In celebration of Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination at the Met, Osman Ahmed remembers McQueen’s searing A/W96 show that would propel the designer to fame

In the month Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination opens at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, anothermag.com is running a series of The Shows That Matter on collections that tackled religion, head on. First, Osman Ahmed considers Alexander McQueen’s A/W96 Dante collection, which would propel the designer to international acclaim.

Alexander McQueen will forever be embedded in history as one of the most provocative and subversive fashion designers to have defined the era in which they lived. McQueen’s shows were often fashion’s equivalent of a psychological thriller – dark, intense and twisted. Yet, often they were also eye-wateringly romantic and brazenly sexual – weaving heavy ideas into exquisitely cut garments presented in theatrical gestures. This month, the cockney designer’s work will return to The Metropolitan Museum of Art for the first time since the blockbuster Savage Beauty exhibition in 2011. In Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination, the Met’s largest exhibition to date, McQueen’s work will take centre stage alongside Gothic altarpieces in the exhibition – a meditation on the sartorial use of religious iconography and symbolism.

Of course, religion was a fascination for McQueen throughout his career, but no collection dealt with it as squarely as Dante, the designer’s Autumn/Winter 1996 show, which was staged in Christ Church, Spitalfields on March 1, 1996. The collection was named for the 14th-century Italian poet whose Divine Comedy portrays an allegorical vision of the afterlife, and the show, as McQueen relayed to Women’s Wear Daily at the time, was about “war and peace through the years”. In fact, McQueen went further by decrying institutional power. “I think religion has caused every war in the world, which is why I showed in a church.”

According to his collaborator Philip Treacy, Dante was the show that bolstered McQueen’s career and catapulted him to international acclaim. “The thing is, everybody loves Alexander now, but they didn’t at the beginning,” Treacy told The Cut in 2015. “When he did that show, suddenly people could see his potential, because it was beautifully done.” Indeed, WWD openly hailed McQueen as “the saviour of London Fashion Week” just three days after the show. “The overall feeling after four days of runway shows was flat, with most of the city’s young designers again failing to deliver on their initial promise,” wrote fashion critic Bridget Foley. “The diminishing excitement about London fashion is the reason that many American retailers skipped its shows and elected to head straight for Milan.” What ensued was a career-changing show for McQueen, which would lead him down the not-so-rosy garden path to international acclaim and commercial success.

The Show

Christ Church itself was built by Nicholas Hawksmoor, believed to be a secret Satanist, between 1714 and 1729. McQueen’s mother, Joyce, was an amateur genealogist and told her son that their family was descended from Huguenots who settled in the Spitalfields area, many of whom were baptised and buried in the church. Inside, the scent of roses drifted in the air around the crucifix-shaped catwalk and the pillars of the church were surrounded by candles and a skeleton occupied the seat next to Suzy Menkes. “If I get someone like Suzy Menkes in the front row, wearing her fucking Christian Lacroix, I make sure that lady gets pissed on by one of the girls,” he once told a journalist. Many of the crew members remember McQueen relishing in the eeriness of the space – McQueen’s dog, Minter, wouldn’t stop barking and had to be taken home, and make-up artist Val Garland’s rosary beads spontaneously broke. McQueen couldn’t be happier about the spooky ambience.

“There were huge crowds outside – it was mayhem,” remembers Susannah Frankel, AnOther’s editor-in-chief. “It was funny because it was the established fashion audience but also Lee’s friends, people who were there because they were in his world, so it was quite a clash of cultures and everyone was so, so excited.” Guests assumed that Christ Church was deconsecrated, but as it turns out, it wasn’t and the parish subsequently wrote to newspapers after the show to point this out. “Lee was always so irreverent,” adds Frankel. “I’m sure he loved that.”

Paint it Black by The Rolling Stones and fragmented sounds of helicopter blades from the 1979 film Apocalypse Now filled the church, followed by LL Cool J’s Mama Said Knock You Out, which was subsequently subsumed by disembodied Gregorian chanting as lighting designer Simon Chaudoir’s 20-kilowatt light exploded through the stately stained glass window of the church. The show came at a time when fashion was becoming unfashionable – Sharon Stone had worn Gap to the Oscars earlier that year, and it girl du jour Chloë Sevigny announced, “I’m trying to be anti-fashionable”. Two films were defining British society at the very moment: Danny Boyle’s Trainspotting, a gutsy, gaunt and surreal story of Scottish heroin junkies, and Sense and Sensibility, Ang Lee’s lush period Austen romance, laced with 90s irony. McQueen, as it turns out, managed to artfully capture and combine the essence of both.

The People

“I remember Isabella [Blow] incessantly clapping, because she wanted everybody to love it. She used to invite people to his shows – she used to make people go to his shows – and then she would come and see me afterward and she’d be so disappointed,” remembers Treacy. “She’d say, ‘That person said that maybe Alexander should make costumes. Costumes?’ They didn’t get it. People would love to pick holes in things, but Isabella was his defender.”

Much of the Victoriana influences could be traced back to Blow, who was a mentor and patroness to McQueen, right from his Central Saint Martins graduate show which she bought in its entirety with £100 weekly payments. The casting of the show was a mix of aristo-models such as Honor Fraser, who wore Shaun Leane’s silver crown of thorns, and South Asian models who were representative of the local Brick Lane community, dressed as the gangs of Hispanic teens in Paul Morrissey’s 1984 film Mixed Blood. Dante was also the first time that a young Kate Moss appeared in a McQueen show.

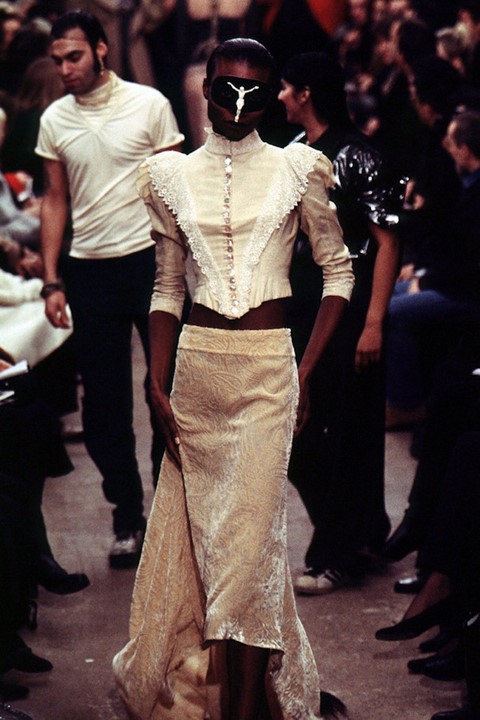

Sartorially speaking, there were incendiary slashed sleeve jackets, bumster cadet trousers with sharply-angled cuffs, brocade admiral’s coats, deconstructed gold bullion jackets, lilac half-morning corsetry, antler headdresses, bird claw earrings and crucifix-covered masks. Less overt were references to early Netherlandish religious paintings, reflected in the cut, construction, and layering of some of the garments such as the bias-cut pinstripe flannel suits. McQueen also borrowed from his favourite photographer Joel-Peter Witkin, in particular the mask with the figure of Christ crucified, which he took from Witkin’s 1984 portrait titled ‘Joel, New Mexico’.

Dante also marked an elevation in McQueen’s production, thanks in part to some income from a Japanese licence with Onward Kashiyama. The Mongolian wool-trimmed wool coats, bumster trousers and spliced suits in grey and lilac were being made in Italy and the haute corsetry was a collaboration with Mr Pearl. The face shrouds and body suits, however, were made from cheap lace purchased in Berwick Street market. Meanwhile, the draped devoré velvet dresses and skirts were made in-house and the bleached denim was knocked up by Andrew Groves in the bath of his studio flat.

Traumatic images of the Vietnam war and the Somalian famine, taken by war photographer Don McCullin were printed throughout the collection. However, the prints were pirated – sneakily printed by McQueen’s friend Simon Ungless using Saint Martins’ print room facilities. Ungless also borrowed rare feathers and horns for accessories from his gamekeeper father, and Philip Treacy mounted a set of antlers onto a headpiece. “Lee loved those [Don McCullin] pictures, and I’m assuming out of sheer naivety, he thought he could print them onto his clothes,” remembers Frankel. “In fact, that wasn’t the case because the rights didn’t belong to him and he didn’t ask permission. I love the fact that afterwards there was a row and then he became friends with Don McCullin and they collaborated.” To this day, McCullin continues to work with Sarah Burton, photographing her collections for Alexander McQueen in the atelier.

The Impact

Dante came at a time when the work of many designers was so derivative, it was almost akin to necrophilia. Dante was presented twice, the second show staged in a disused synagogue on New York’s Lower East Side, which was so packed that even the almighty Anna Wintour herself couldn’t get in. It marked the beginning of art-directed shows for McQueen, who would take the helm of Givenchy later that year and take on a majority investment from Gucci Group (now Kering) in 2000. “I think perhaps it was the first time he started thinking more like an art director, thinking about the set, the lighting, the venue, the atmosphere beyond the clothes,” says Frankel. “In the end, that was hugely important to him.”

As fashion historian Judith Watt recalls, in her definitive book Alexander McQueen The Life and the Legacy, “The links between Dante Alighieri, the Florentine fourteenth-century poet and author of The Divine Comedy were implicit at first, but the strange fusion of the inferno of life with the inevitability of death gradually became obvious.” McQueen’s Dante treaded the fine line between performance art and fashion spectacular, but essentially conveyed both. As a new documentary explores the designer’s life, the show is now more pertinent than ever. “If you leave a show without emotion, then I’m not doing my job properly,” he says in the documentary. “I don’t want you to walk out feeling like you’ve just had Sunday lunch. I want you to be repulsed or exhilarated – as long as it’s an emotion.”

Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination at the The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York runs from May 10 – October 8, 2018.