From Gucci’s double G to the the Moschino smiley face, a new exhibition on Italian fashion traces the frenzy of logomania

Much has been written about the boisterous resurgence of logo culture in recent seasons. Its impact on fashion is hard to overstate – whether described in awed tones as an ironic subversion of consumerist society, or disregarded as an epitome of ‘bad taste’, the designer logo is an inescapable symbol of modern fashion.

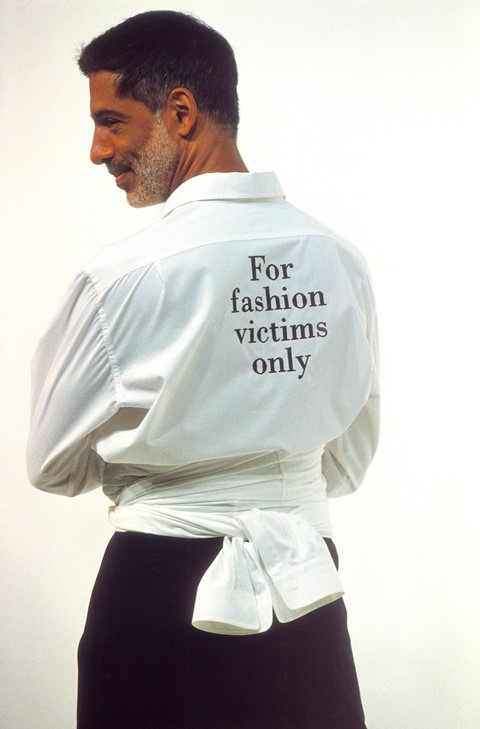

Now, a major exhibition is revisiting the formative fashion legacy of the logo and exhuming some facets of its lesser-known history. Held at Milan’s Palazzo Reale and curated by critic Maria Luisa Frisa and editor of W Magazine Stefano Tonchi, ITALIANA: L’Italia Vista Dalla Moda 1971-2001 purports to examine three seminal decades of Italian fashion through the cultural leitmotifs that most strikingly defined it. “The show focuses on the transitional period between haute couture and the birth of prêt-à-porter and industrial design,” Tonchi says. “1971 was a crucial year – that’s when Walter Albini first made the move from Florence to Milan, where all the factories were, to start creating clothes that were industrially produced.”

The logo played a key role in this shift towards industrialisation, which dissolved the icy image of high fashion as an elitist club only a privileged few could gain access to. “The idea of transforming a design into a product that can reach a large number of people wasn’t really popular in France or England, but it became inherent to the Italian ethos,” Tonchi asserts. “Albini was an industrial designer rather than a couturier, as was Gianfranco Ferré, and countless others; the birth of logomania was part of this greater attempt to democratise high fashion, create a product that is high quality but that could be for everybody.”

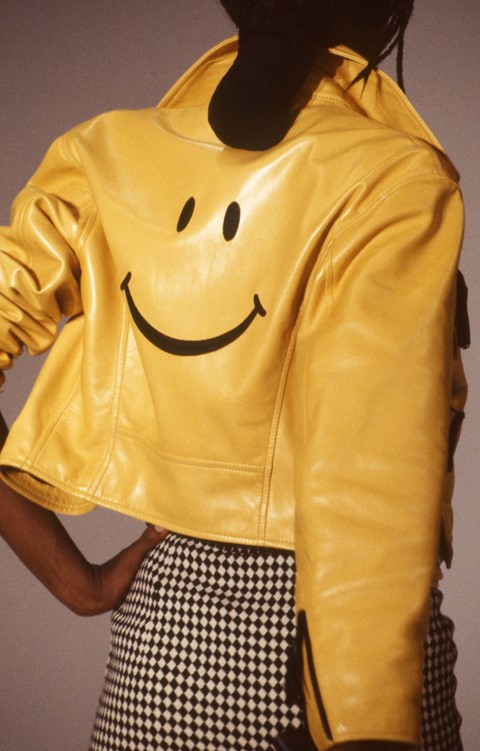

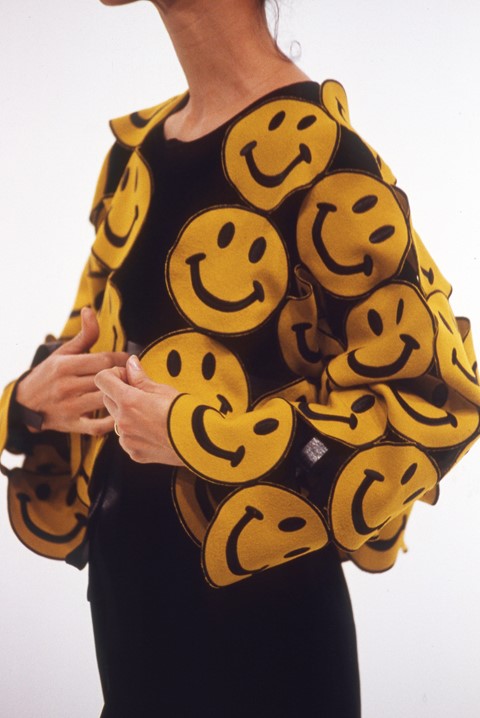

The logo movement started slow, but soon became revered as a game-changing cultural and aesthetic phenomenon. As early as the 1960s, Valentino was already embellishing his garments with a signature V; in the 70s, Walter Albini’s embroideries invariably bore his initials. A long list of iconic names followed suit, using initials, prints or patterns to create and communicate their own distinct, collectively enjoyable universe. As a result, the Armani eagle, the Versace Medusa, the Gucci snake, or the Moschino smiley face all became instantly recognisable symbols of fashion’s desire to be more democratic.

“When logomania reached its peak, in the 90s, it stopped being just about the clothes – it became a lifestyle,” Tonchi says. “After Giorgio Armani came Emporio Armani, followed by Armani Jeans, and then sportswear or home decoration.” As such, the logo allowed designers to reach a significantly larger audience and make a once exclusive dream accessible to many. “Ultimately, it’s about offering a point of entry to everybody. You can be a part of the Gucci world even if you just own a wallet, or a keychain.”

Today, the revival and reinterpretation of the logo remains as timely as ever, with the likes of Vetements and Balenciaga continuously reminding us of its unrivalled cultural relevance. While its function has become seemingly antagonistic, going from the democratisation of luxury to the elevation of banality, the appeal of the logo continues to seduce. “We are still obsessed with logos today, despite the shift in our approach to it,” concludes Tonchi. “Ultimately, it’s come full circle.”

Italiana: Italy Through the Lens of Fashion runs at Palazzo Reale, Milan until May 6, 2018. The accompanying book is available here.