It was 2012 when American documentary filmmaker Steve Hoover first came across Gennadiy Mokhnenko – the Ukrainian vigilante pastor around whom Hoover’s latest film Almost Holy is centred, who has made a name for himself in the south-eastern city of Mariupol by “forcibly abducting homeless drug-addicted kids from the streets” and taking them back to the centres he runs through his charity Pilgrim.

Hoover was in the final stages of post-production on his 2013 debut, the critically acclaimed Blood Brother, and was seeking out a subject for his next film. Some of his production team had encountered Mokhnenko while shooting a video in Ukraine and, after spending a few days with him “listening to his stories and witnessing his amorphous work”, they returned convinced that the charismatic man was the perfect focal point for Hoover’s next project. “I hadn’t met him, so I didn’t share their enthusiasm at first,” the director explains. “But they really worked hard to contextualise everything for me, to help me to understand Gennadiy; they sat me down and showed me a lot of raw footage and suddenly it just kind of clicked.”

One of the things that most struck Hoover about the pastor was “the connection he had with the kids – how he was this forceful figure in their lives. It turned the lights on for me.” Hoover had been a troubled teenager himself, “obsessed with hallucinating... the drugs were boundless”. He recognised that, had he been born in Mariupol, “Gennadiy would have had me by the collar”. But, he writes in his director’s statement for the film, “I found deeper interest not in the kids I empathised with, but in a character I didn’t understand. The story could have gone in many different directions.”

Indeed, when he first touched down in Ukraine – having gained enough money for the film’s early production via a Kickstarter campaign and on-boarded directing veteran Terrence Malick as an executive producer – Hoover really had no idea what to expect. “I went in pretty cold turkey, and I don’t speak Russian, but it was great because it was a constant process of exploration and discovery,” he tells us. “We flew into Donetsk airport, which is now destroyed, and Gennadiy came with a couple kids and ran over and grabbed all of our stuff; straight away it seemed like he had this endless pool of energy. It was probably 1 or 2am when they picked us up, and we had an almost two-hour drive to Mariupol, and he talked the whole way. I wasn’t planning on shooting as soon as we got there but I couldn’t help it – it was my first encounter with this guy, and he had this magnetism to him and his stories are fascinating. So I had our DP pull out the camera and we started right away.”

What Hoover would go on to encounter in Mokhnenko’s presence, however, would not make for such palatable viewing. Over the course of the film, the crew follows the formidable samaritan as he yanks children out of sewers, and away from the sinister advances of a child molester (whom he beats savagely), and pulls them from drugs dens before demanding who their dealer is and setting out to confront the villain in question. Yes, moral ambiguity is an underlying theme in the film, and Mokhnenko is, to say the least, an extreme character but as Hoover points out, “this is the sort of place and world he is functioning in”. “I really tried to put things into context for the viewers,” he explains, “and my hope is that people will do their best to disconnect themselves from their own known experiences and try to understand that where he is coming from is a completely different place.”

Unquestionably, there are many people, both young and old, in Mariupol who, without the help of Crocodile Gennadiy (as Mokhnenko has nicknamed himself, after the reptilian hero of a Soviet cartoon) would be left to suffer indefinitely. A small girl living with her mother in a filthy house, filled with rubbish and cats, explains without so much as blinking that her father hung himself with a telephone cord in the corner of the room; a woman with severe mental health and learning difficulties struggles to articulate her terror at the hands of a rapist who is holding her hostage: Mokhnenko’s world is not our world, and the pastor feels that his hands-on approach is the only thing he can do to counteract it.

Just as one starts to feel a glimmer of hope on the horizon as a result of the pastor’s relentless passion and determination, however, another even more foreboding force looms. “My dream for each family home,” Mokhnenko muses after a wholesome, home-grown meal shared with his wife, children and many adoptees, “[is] adopted children with parents, little greenhouse, and little house for chicken. Maybe 20 chickens... super! However,” he continues, “we dream about good time but we must prepare for bad time”. And, as predicted, a violent invasion by Russian forces ensues.

Hoover and his crew were also caught up in the warfare – finding themselves at the centre of a forceful attack, while driving in a van with Mokhnenko. It was a near-death experience that shook the American director to the core, leading him to renounce his faith thereafter. He wrote an in-depth article on the encounter for Vice, but chose not to include any decipherable footage of the attack in the film. “I tried a handful of ways,” he says when we ask why that was. “You’re editing a film where there are so many different ways to go and at one point I tried to incorporate that [part], but it felt like such an unnecessary departure. I think what was important about what happened was that violence came to Mariupol and violence came to Gennadiy and this thing was completely unavoidable, but trying to put us in as characters felt really disjointed.”

“Also, I didn’t want to make a political film,” Hoover muses. “I think whatever sort of politics that exist within the film are a result of the characters and how they think and feel versus a message I’m trying to propagate.” And indeed, the only sense of a director’s commentary upon the country’s situation comes indirectly from the clever snippets of the aforementioned Crocodile Gennadiy stop-animation inserted throughout the film. (“It became a great narrative device because it contextualises the different cultural elements and the decisions that Gennadiy was making, but in such a nostalgic and fun way,” says Hoover).

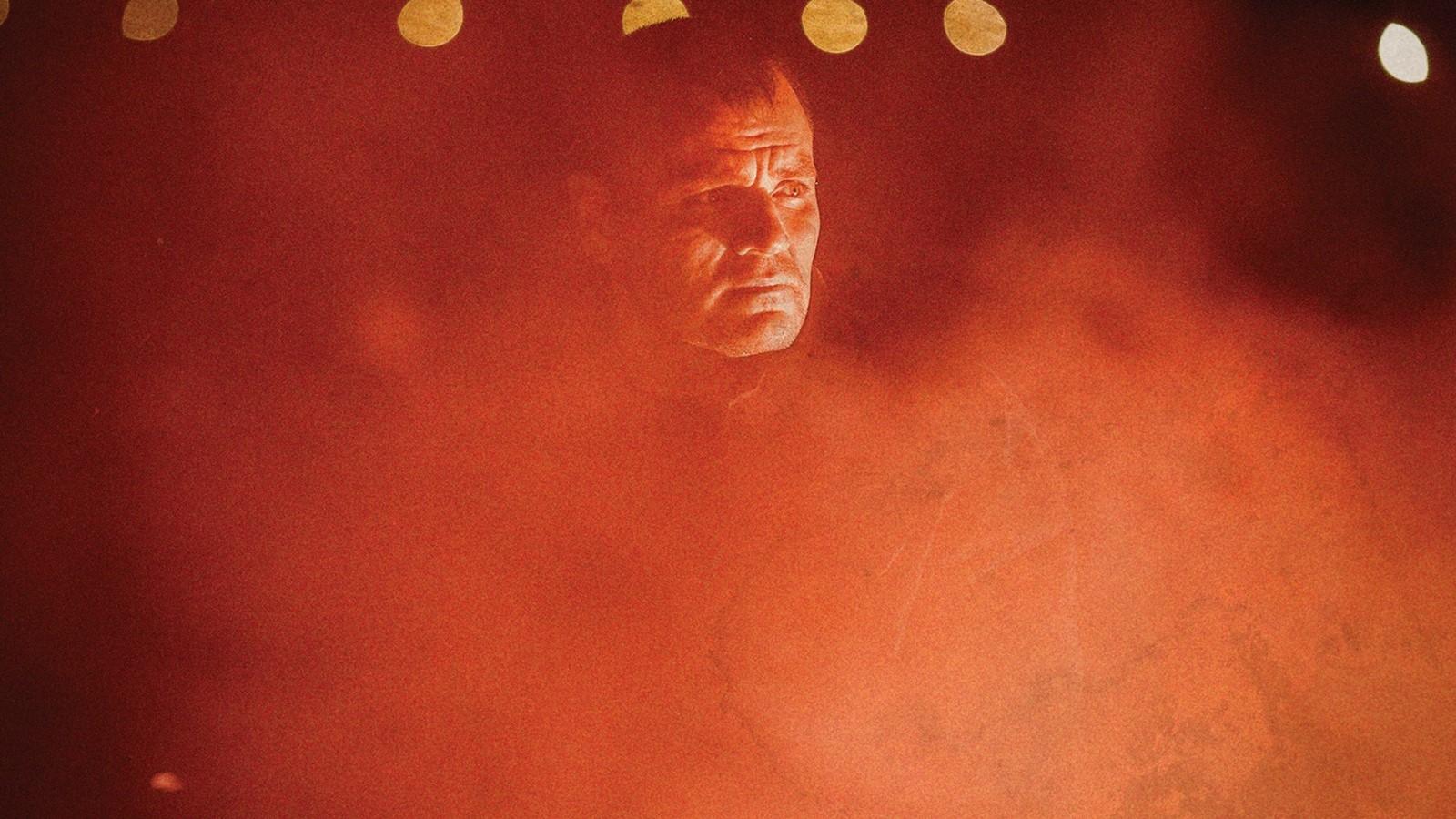

Sweet cartoon characters aside, Almost Holy is often unbearable to watch in its explicit (although beautifully shot) candidness and gritty exploration of human suffering. But it is vitally enlightening, and inspiring, and lingers uncomfortably in the back of your mind long after viewing. Unsurprisingly the impact its realisation has had on its director is enormous. “Trying to quantify the effect of that experience on my life is hard, but being attacked by a group of people and spending a year in an edit suite looking at footage of kids that are littered with track marks and of drug abuse and kids in coffins, all that stuff changes you.”

So, will Hoover seek out a more optimistic project to embark upon next? “The way I function is, if something strikes my interest then it’ll pull me in – whether that is a harrowing story like Gennadiy’s or a comedy. I wanted to tell these stories, to capture what I see and experience and relay that to another person to see how they think and feel about it. But I would like to do lighter material,” he concedes. “I’m not a thrill-seeker, I don’t want to go into war zones; some people do and they thrive off that and that’s amazing but I’m just not there, and having a brush with it and seeing bloodlust in somebody’s eyes, I don’t like it, it’s not something I’m looking for."

Almost Holy is in cinemas from August 19, 2016. Watch the trailer here.