As a nationwide touring programme of her visionary work begins, we explore the life and work of the ‘grandmother of the French New Wave’

Agnès Varda is one of the great filmmakers of the 20th century, and – rather amazingly, given that she is now approaching her 90th birthday – 18 years into the 21st century, she shows no sign whatsoever of slowing down. Her most recent film, Faces Places, a documentary made in collaboration with the photographer and muralist JR, was nominated for an Oscar earlier this year, making the so called "grandmother of the French New Wave" the oldest person ever to be put forward for the award. For decades, Varda has quietly devoted herself to her art, constantly experimenting with new techniques and media to capture the world through her own, entirely unique, lens – producing some of cinema's most poignant, funny and fabulously feminist films along the way. But it's taken the world a long time to catch up, and finally recognise Varda as the filmmaking marvel she has long been.

Happily, this year is very much her year: her work has been the subject of a two month season at the BFI, titled Agnès Varda: Vision of an Artist and running until the end of July, while a nationwide, Curzon-produced touring programme of eight of her films kicks off next week, a timely celebration of Varda’s brilliance in the build-up to the UK release of Faces Places in September. Here, we catch up with Aga Baranowska, curator of the Varda season at the BFI, to bring you an essential guide to the Belgian-born, French auteur’s inimitable oeuvre.

1. Her work merges documentary and fiction to unique effect

Varda made her first film, La Pointe Courte, in 1955, diving into the world of cinema with very little prior knowledge of the medium and no schooling at all (she was working as a photographer up until that point). The bold, stylistically daring film centres on a married couple attempting to restore their failing marriage and is set against the the humble French fishing village of Sète. Varda punctuates the lovers’ lengthy conversations with snapshots of the lives of the village's poor but proud residents and their struggles for survival.

“Watching La Pointe Courte, you can see from the very beginning that Varda has taken an experimental approach to the film form, mixing documentary and fiction,” Baranowska explains. “The film is basically two stories. One about the married couple – the fictional element – but then another about the villagers, who we really get to know. It all takes place in the same place but on the other hand they could be completely separate films.” This mix of documentary and fiction, the curator notes, is something that Varda has actively continued throughout her career and has come to be viewed as one of her most defining, pioneering traits. A wonderful later example of this can be found in her 1991 film, Jacquot de Nantes, a fictional exploration of the early life of Varda’s filmmaker husband Jacques Demy, lovingly interlaced with documentary footage of him in later life.

2. She is a fiercely political filmmaker

Varda has always made films that confront contemporary politics head on. Early examples of this include her two short films about the Black Panthers, Huey and Black Panthers, both focusing on the demonstrations held in support of Huey P. Newton, co-founder of the political party, who was arrested after shooting a policeman. She also examined various political causes through fiction, perhaps most memorably in her 1977 musical One Sings, The Other Doesn't – centred around two female friends in rural France, one of whom is set upon having an abortion – and her celebrated vérité drama Vagabond (1985), about the death of a passionate young drifter named Mona. “One Sings, The Other Doesn't is a very personal film to Varda because she was involved in the abortion movement in France prior to its shooting,” says Baranowska. “And it's entirely influenced by what was happening in terms of the women's liberation movement in France in the second part of the 70s.” Indeed, the film depicts a reconstructed protest outside the famous Bobigny abortion trial in 1972 and includes a cameo appearance from defence lawyer Gisèle Halimi, who argued the case for various women who had admitted having abortions.

But it was in Vagabond that Varda said she felt her filmmaking and politics collided to most satisfying effect. “It was inspired by the story of a woman that was found frozen in a field,” Baranowska tells us. “Before making the film, Varda talked to a lot of women who were either homeless or didn't have a permanent home and she built the tale of Mona around their stories.” The result, Baranowska notes, is truly penetrating, the film’s various interviews with the people who last saw Mona forcing the viewer to consider their own sense of social responsibility.

3. But also a very funny one

Varda’s work is not all designed to be so hard-hitting, however. She is a deeply humorous and playful personality, as a watch of her brilliant autobiographical documentary Beaches of Agnès attests with its opening line, “I’m playing the role of a little old lady, pleasantly plump and talkative, telling her life story”. The film also includes a joyful introduction to the subject of French New Wave cinema by Varda's friend and fellow filmmaker, Chris Marker, presented in the guise of an orange cartoon cat – another embodiment of Varda's eccentric, non-stuffy outlook. “That's my favourite example of her humour,” Baranowska agrees.

Her sense of humour has sometimes landed Varda in hot water, however, as in the case of her third feature, Le Bonheur, which depicts what the BFI term “a paradise for men and a dystopia for obedient women”. The film caused outrage among some viewers at the time, with a handful declaring it anti-feminist. But those familiar with Varda’s humour can spot the veiled irony behind this depiction of a shiny male utopia where women are little more than commodities. As Varda once said, “Humour is such a strong weapon, such a strong answer. Women have to make jokes about themselves, laugh about themselves, because they have nothing to lose.”

4. A love of art – in all its forms – defines her practice

Varda embraces art in all its guises – from her training and early career in photography, which she has continued to pursue both within and outside of her filmmaking (“I take photographs or I make films or I put films in the photos, or photos in the films,” she once explained of this fluid interchange) to her recent forays into installation art and her embracing of digital technology, including Instagram. “The theme of the BFI season is Varda as an artist,” says Baranowska. “I wanted to show that, while many think of her move into art as being a recent thing, her interest not only in cinema as art but in art in general comes through in her work from the very beginning.”

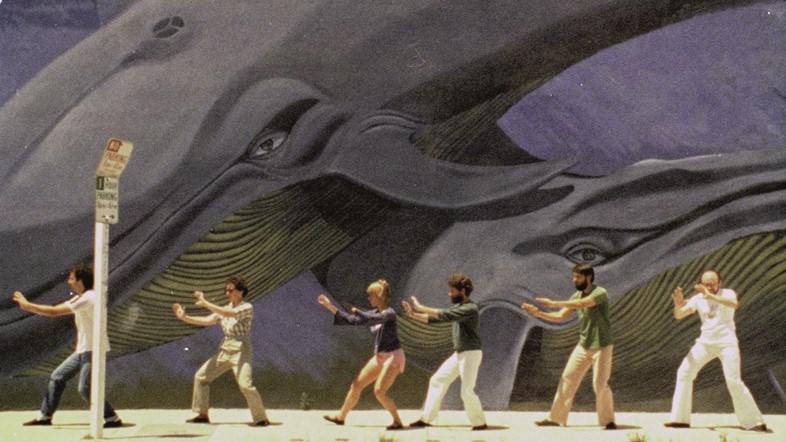

La Pointe Court’s photographic style is proof of this, the curator says – “some of the frames could be still images, beautiful photographs” – while Le Bonheur, with its sumptuous, painterly colour palette (it was filmed in the gardens of Île-de-France, a source of inspiration for the French Impressionists) is another early example of this. “Another key film is The Gleaners and I," Baranowska continues, talking of Varda's thought-provoking 2000 documentary about scavenging culture in France. “It's about people who use found objects in new ways and I believe that here Varda is looking at what it means to be creative, what it means to be an artist or a filmmaker creating something.” Varda's interest in other people’s creativity as well as her own also manifests itself in films like her 1988 docudrama Jane B. for Agnès V., made in collaboration with Jane Birkin and exploring what it means to be a muse, as well as, in Baranowska's words, “how the idea of a star is really built as a creative force”. “Then there's Mur Murs, where she looks at artists in LA who do outdoor murals, and Faces Places with JR,” she adds. “The creative process really is an enduring source of fascination for Varda.”

5. She changed how women were represented on film

One of Varda’s most important legacies in an industry still dominated by men – she was one of the 82 women who led a red carpet demonstration at this year’s Cannes to protest women’s secondary status in cinema – is her ongoing dedication to investigating women's issues and conveying what it means to be female in the modern world. Two of her most stirring works in this respect are her acclaimed 1962 drama Cléo from 5 to 7, the insightfully fleshed-out portrait of a singer awaiting the results of biopsy and pondering her own mortality, and Vagabond, which is widely celebrated for its de-fetishisation of the female body from the male perspective.

“Vagabond is one of my favourite films she has made,” enthuses Baranowska, “and one of the reasons is because of the protagonist, Mona. She is so uncompromising, so stubborn; she knows that she wants in life and I think that's so refreshing. I personally haven't seen that many films with protagonists like her – even now – which is why the film is so vital.” The curator is quick to add, however, that Varda is not merely a feminist filmmaker (a label that's easy to attach to any female director who tells women’s stories in their work). “She has of course created so many important, influential female characters in cinema so she is a feminist in that sense, but she's also so much more,” she says. “A couple of weeks ago, at a Q&A after a screening of Beaches of Agnès, she was asked about being a feminist, and her reply was that her main concern has always been to reinvent cinema and be proud and happy as a woman.” Both of these ambitions Varda has undoubtedly succeeded in, carving out a path in filmmaking unlike any other, while flying the flag for women, both as creators and complex beings – statuses that cinema has long denied us.

Agnès Varda: Gleaning Truths commences its tour of eight of Varda's films nationwide on August 3, running until September 21. Agnès Varda: Visions of an Artist as at the BFI until the end of July.