Stills and clips from the archives of Sirio Luginbühl are on display in Padua now

Who? Sirio Luginbühl was a man who saw cinema as an intimate act: “To a filmmaker a movie is like a son, it is always the result of an act of love, a cinematographic orgasm”. After graduating in sciences from Padua, the Veronese filmmaker fell hard for the arts in the electric energy of the 60s, and soon found himself at the centre of Italy’s neo-avant-garde, drinking with the Novissimi poets and directing the literary section of the Enne Studio.

Now famously the home of Gruppo N, an artistic collective founded by Alberto Biasi and Manfredo Massironi, the studio provided the creative hub that fostered Luginbühl’s love of film. Watching the experimental draughtsmen conceive and create works in collaboration, play with perceptions, and uncover optical illusions helped to fuel Luginbühl’s vision for a new kind of filmmaking. His unique creative and critical eye also saw him go on to author several texts on experimental and underground cinema, and co-found the city’s Independent Cinema Cooperative in 1970.

What? After his death in 2014, a retrospective of Luginbühl’s work has finally been digitised and archived, with the help of his wife and daughter. The collection at Padua’s Palazzo Pretorio presents the unique opportunity to view Luginbuhl’s shorts which for too long have been kept out of the public eye; with looped projections in a series of room,s the brief but intense scenes that made Luginbühl’s name are played out on repeat.

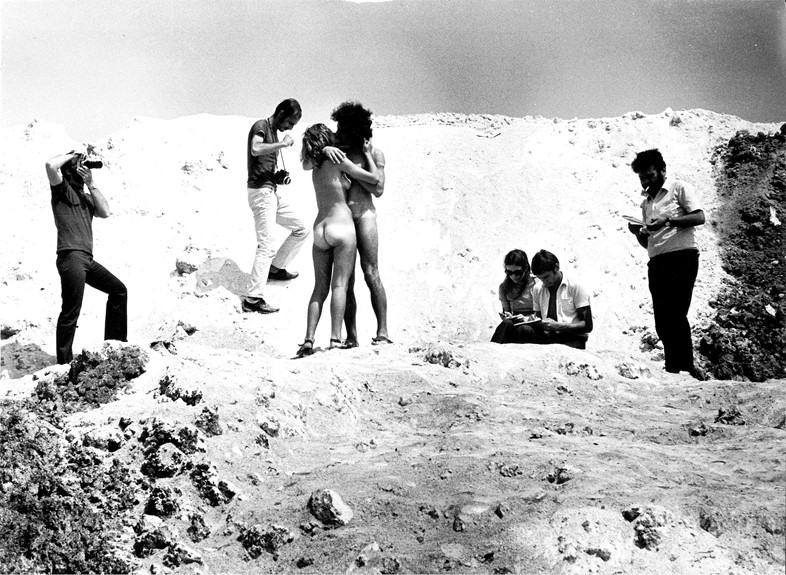

Although many of the films were created in reaction to events at the time of their creation, the themes of sexual liberation, consumerism and pollution ache with contemporary resonance. One particularly poignant work explores the impact of setting on emotion: two naked figures stand in the wilderness, a modern Adam and Eve in a barren Eden. The primitive becomes mystical in Luginbühl’s gaze, raising the central question, “could one love in such a hostile and violent environment?”

His characters “had never seen each other before that time, both of them were beautiful and unaware of what to do”. In the midst of the wasteland he asked them to kiss, to create a moment of beauty between themselves. And they did; intimacy exists in the unexpected. As with many of his films, he was adamant that spontaneity should underpin the structure. “It had to be a surprise for them too,” he said, “and so it was.”

Why? The 60s were a pivotal moment in cinematic history, and unsung pioneers such as Luginbühl paved the way for a new kind of filmmaking. Film became not merely a commercial medium, but an art – a tool with which to play, to provoke and to ask questions.

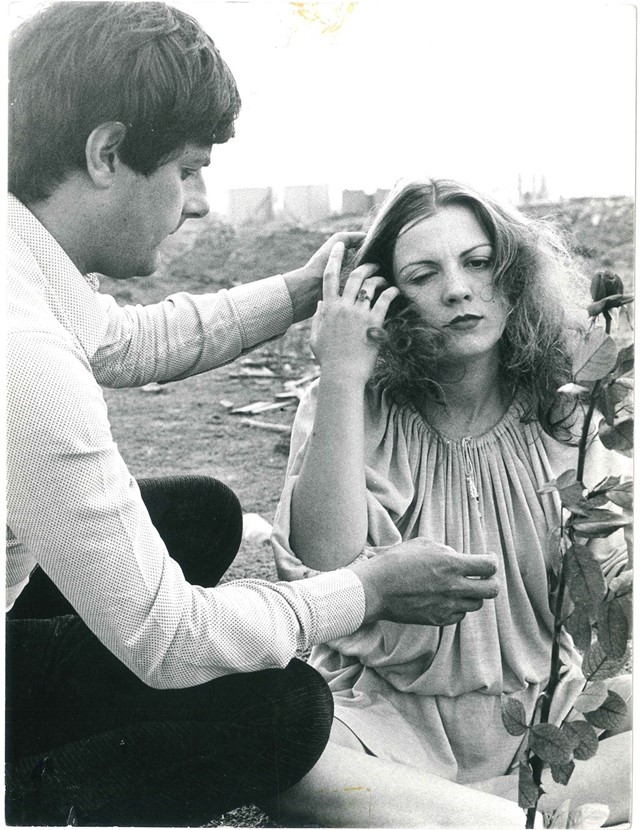

If a full-length feature film is a novel, Luginbühl’s shorts are novellas, meditations, fragments, or even poems. His film stills alone present compositions which evade the construction of their original form. Made to move, they sit contentedly still: a couple embrace on a church altar; a woman runs naked up a flight of stone stairs; a doll protrudes oddly from a fissure of volcanic land. Luginbühl’s expansive archive exemplifies the power such inquisitive and exploratory attitudes can have in front of the camera.

“Ours is a kind of cinema that wants to set itself apart,” he said, “a cinema that wants to be a return to nature, to arouse a valid theme in the spirit of the viewer, a cinema that wants to start over again.” In a world saturated by ever-changing screens, Luginbühl’s vision of connection through contemplation remains quietly radical.

Sirio Luginbühl: Experimental Films. The Years of Protest runs from April 15 – July 15, 2018 at Fondazione Palazzo Pretorio, Padua.