Learning from Patience Gray, the free-spirited wordsmith who extolled the virtues of drinking wine with dinner and running away to Italy

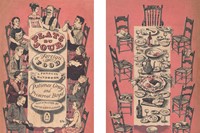

Who? Born on Halloween of 1917, Patience Gray was a visionary English food writer, perhaps best known for co-scribing Plats Du Jour, the bright pink-covered cookbook which introduced French dishes like Breton fish soup and Boeuf en Daube into British kitchens in the late 1950s. But there’s more to Gray than that, and so in what would’ve been her 100th year, it’s right that her eclectic life is celebrated in a new (and deliciously detailed) biography; Fasting and Feasting: The Life of the Visionary Food Writer Patience Gray, introducing new generations to her dazzling fusion of joie de vivre with a no-bullshit attitude. A combination which is surely the guiding force for a life well lived.

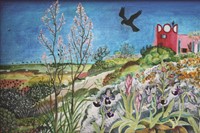

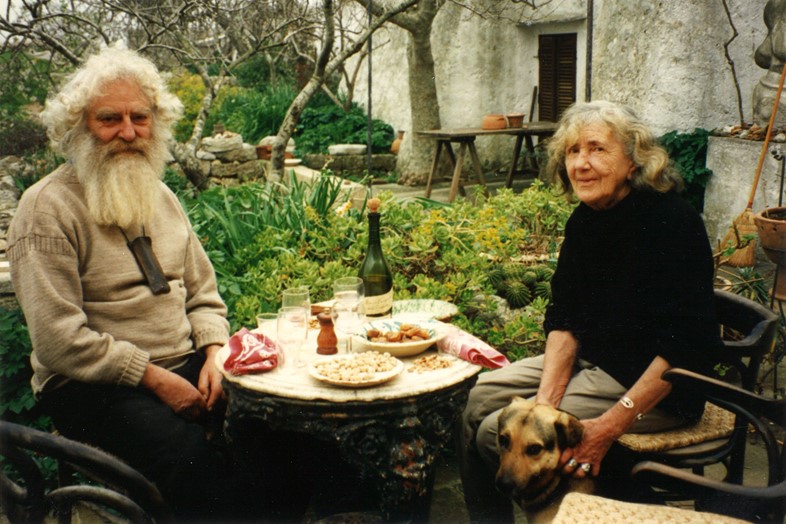

What? After raising her children alone – no mean feat in the 1940s – Gray, who was always an advocate of being good to yourself, spent many years living in Tuscany, Catalonia and the Greek Islands with her partner, the sculptor Norman Mommens, before settling in an isolated farmhouse in Apulia, Italy. There they lived off the land, foraging and slaughtering their own pigs, subsiding according to the whims of the seasons. Of course, she still believed in enjoying a bottle of wine with dinner “wherever possible”, a philosophy espoused in Plats Du Jour.

She wrote about this way of life in her 1986 autobiographical book Honey From a Weed, showing that the pleasure of food can be as much about memory and personal history as flavour itself. She wrote recipes in prose, balancing instruction with vivid anecdote, and peppered with humour. “Mrs Gray lists uses for goose fat,” novelist Angela Carter wrote in a review at the time; “In a cassoulet. In soups. On bread. On toast. ‘On your chest, rubbed in in winter. On leather boots, if they squeak. On your hands if they are chapped.’” Carter added that for Gray, “food is not an end in itself but a way of opening up the world.”

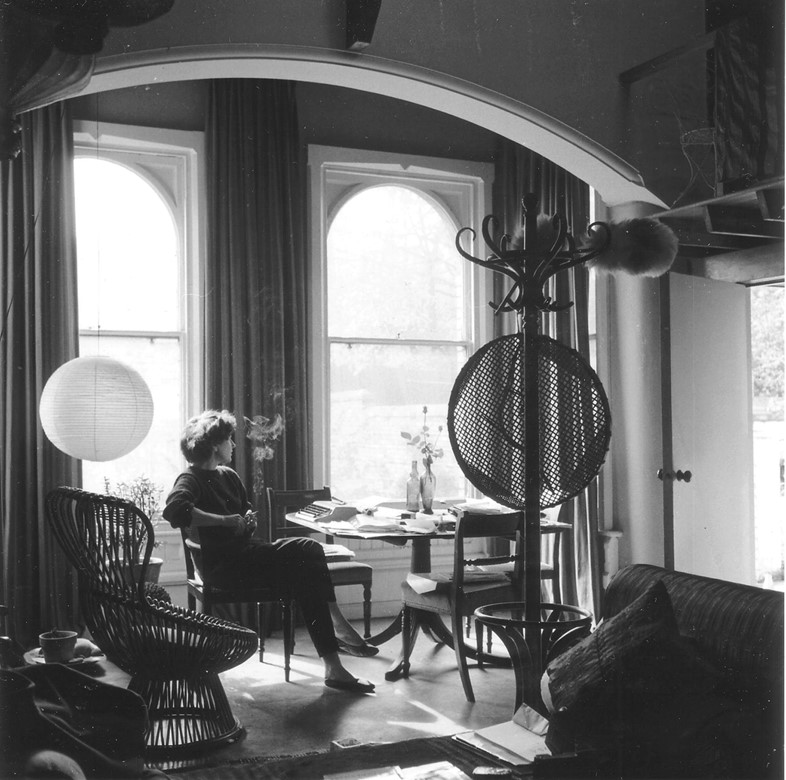

Besides writing about food, Gray was also an avid gardener, collector of antiques, and a funghi enthusiast. As well as editing a book about indoor plants, she was the first women’s editor at the Observer, instructing readers on modern architecture in Milan and European art and habits, much to the surprise of her superiors who expected notes on how to shop cannily. As well as a stint as an assistant at the Royal College of Art, London, she was also part of the team responsible for the thousands of tulips, trees and woodland plants on display at the Festival of Britain in 1951. In short, she is staunch proof that you should and must try your hand at the passions that niggle at you, no matter how new or small they might at first seem.

Why? Until now, an appreciation of the life and work of Patience Gray has been limited to a relatively small circle of food writing enthusiasts and cooks. But in a world in which there are increasing (supposed) requirements to tolerate – from rocketing rent to collective social pressure, and the ever-present craving of wanting more stuff with every thumb scroll – it’s important to celebrate people like Gray, who wasn’t afraid to opt out in favour of a more exuberant existence. Like a life in the Mediterranean, say. In times of doubt, it can be bolstering to remember that you too could move to the bright heel of Italy, eat coppa and share a writing studio with a large black snake.

Fasting and Feasting: The Life of the Visionary Food Writer Patience Gray is available now, published by Chelsea Green Publishing Co.