This Follow Friday we've lined up a handful of Instagram feeds that favour impeccable furniture design

If you've designated your weekend as time to redecorate, or simply to furnish a fantasy home in your head, we’ve found a way to render the task less laborious. The Instagram accounts in the spotlight today offer both the antique furniture purchases necessary to complete a space, or simply some interior design inspiration. Happy scrolling!

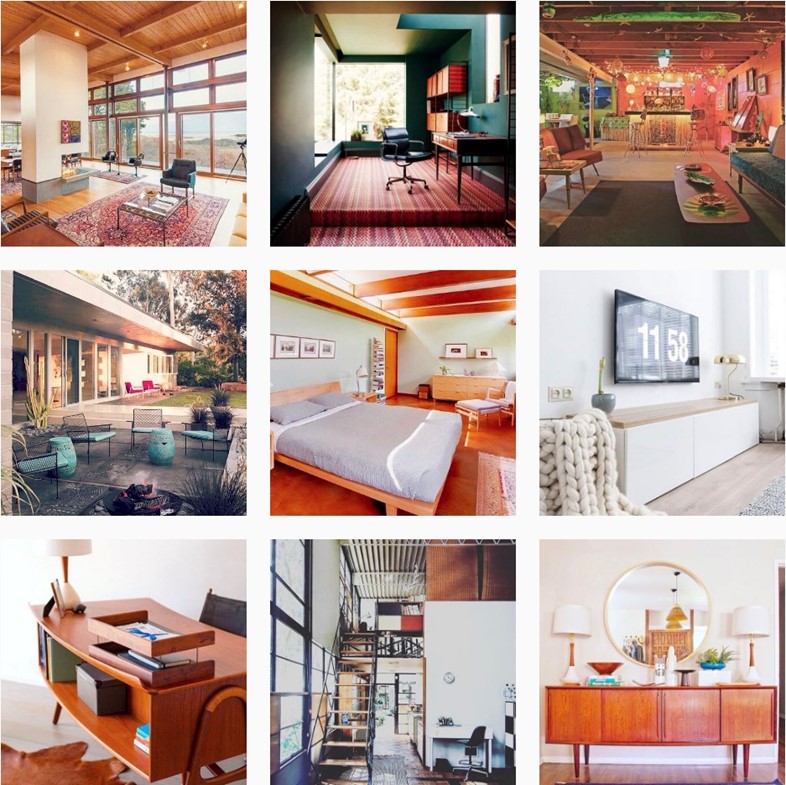

@midcenturyeverything

What is it about Mid-Century Modern furniture that is so damn pleasing? @midcenturyeverything doesn’t attempt to answer such a complex query, but it goes to great lengths to celebrate the movement. The account’s unbridled enthusiasm shines through in its captions – “I think there’s a lot to love in this #midcentury bathroom. What’s the consensus? Yay or nay?” – which sit underneath envy-inducing images of Mid-Century-loaded interiors. It’s a definite yay from us.

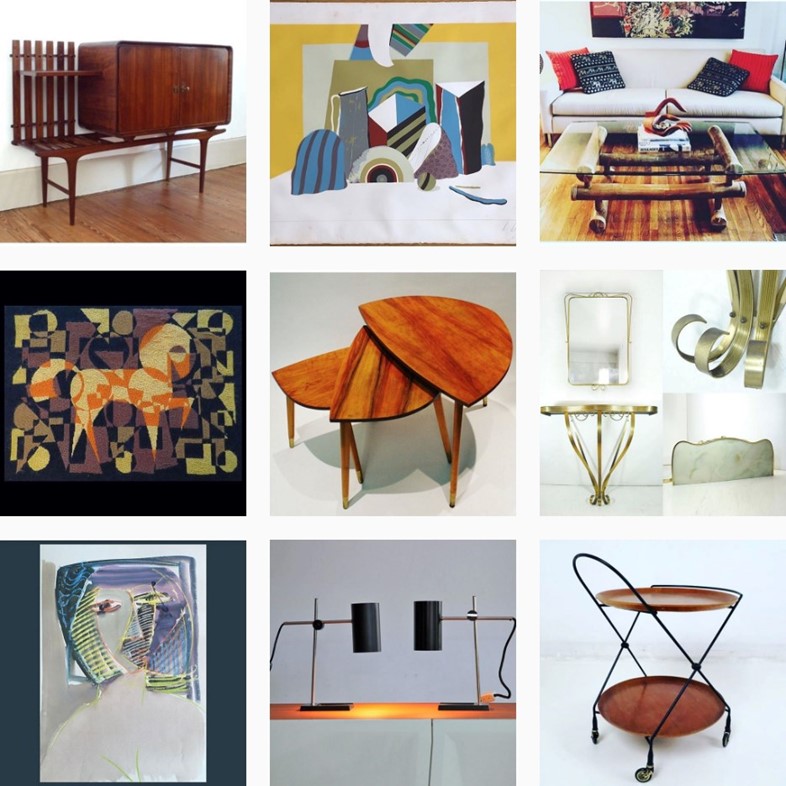

@theartofobject

Vintage clothes aren’t the only things shoppable on Instagram these days: there’s furniture up for grabs too. “Treasure hunters,” reads the bio of @theartofobject, and treasure is what they offer. Everything from tables to paintings, light fixtures to rugs fill up the feed of this account, which operates out of bases in LA, Paris and Berlin. If you’re in need of that one-of-a-kind, slightly kooky, standout piece to complete a room, look no further. Alternatively, this feed makes for excellent moodboard fodder.

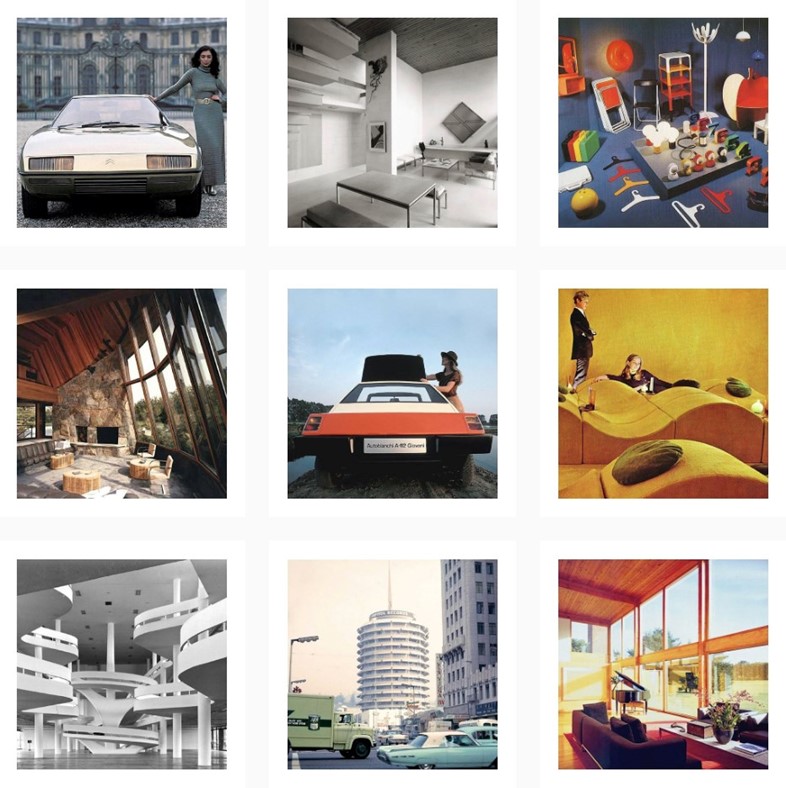

@designtel

@designtel’s artfully curated selection of images is escapism at its very best. Each image has a distinctly retro feel, whether that’s the curvy, space-age white of Villa Fjolle or the sleek wood floor and undulating walls of Palais Bulles. Alongside images of domestic perfection, @designtel also shares shots of vintage cars and vastly impressive architecture – all the components are there to build a fabulous fantasy life.

@sieclesdebrocante

Dealing exclusively in antique furniture, @sieclesdebrocante’s feed comprises unique pieces (all available to purchase) in warm chestnut or beige hues, interspersed with shots of pieces in situ, making up chic scenes which are the epitome of cosy. Think rugged leather sofas or a hanging rattan chair complete with cream sheepskin rug, and Scandinavian sideboards or wicker armchairs. You’ll be flying to Belgium to visit the shop IRL in no time.

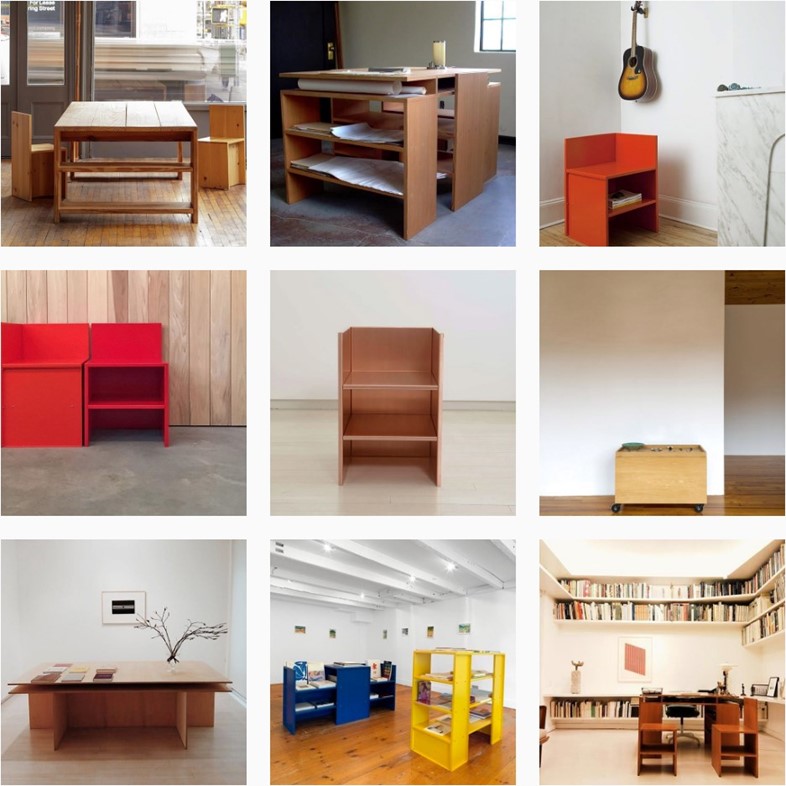

@donaldjuddfurniture

Clean and pared back is the overarching aesthetic of @donaldjuddfurniture. Stark, functional spaces and pieces of wooden or primary coloured furniture to match dominate this feed, with the examples on show designed by the eponymous deisgner – the account is run by the late artist’s Foundation, which has continued to produce Judd’s original designs since his death in 1994. These photographs of side tables, desks, shelves, chairs and the like are testament to Judd’s classic and enduring designs. @donaldjuddfurniture makes for a fitting celebration of this beacon of furniture design.