Cory Arcangel is a name that has become synonymous with the most cutting-edge in digital art over the last decade, and his commission at the Barbican Curve only serves to further his reputation as a conceptual wunderkind.

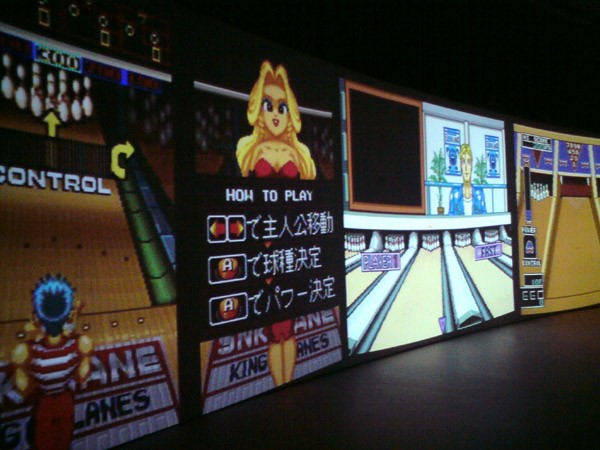

Cory Arcangel is a name that has become synonymous with the most cutting-edge in digital art over the last decade, and his commission at the Barbican Curve only serves to further his reputation as a conceptual wunderkind. In Beat The Champ the Brooklyn-based artist has hacked 14 different game consoles spanning a 30-something year history of gaming – from the Atari to the Game cube – and has programmed them all to play themselves on an endless loop, losing every single time. The game he has chosen to torture the machines with is ten-pin bowling, and various clunky graphic incarnations play inside the space on massive screens. The effect of all the machines playing together is disorientating, not least because of the cacophonous pinball-like sonic effect of the installation. We took some time out with the artist to find out why his latest work is a meditation on the emptiness at the heart of the virtual experience.

Cory Arcangel: "I used bowling games because I think bowling is a really awkward virtual game. It’s maybe the most awkward one I can think of – it’s almost an ambiguous physical game to begin with, so to have a virtual version of that seems almost to be in the realm of the absurd. I was thinking about the notion of machines playing themselves endlessly and poorly – machines versus machines, it’s just so kind of sad and clumsy isn’t it? I was thinking about the most unsuccessful way that this technology I had developed for them to play themselves could be deployed. Theoretically, my technology could play a perfect game on some of these systems but that didn’t seem interesting to me – it seemed a lot more interesting not to have it work at all. The reason I work with video games is not because I’m particularly interested in video games, but because I think they’re one of the things that exist now that represent the way things are going. I mean its like the ‘virtual' human experience. In the last ten years culture has really shifted towards that in a lot of different ways – social networks, iPhones... whatever – and I think that somehow these really weird, poorly rendered 3D characters bowling are in some way related to that shift, or at least that’s my intuitive feeling. I’m definitely not opposed to the way things are going though, because I like to actively position myself in regards to the river of culture, but having said that, culture is moving fast and it’s creating new and different tensions. I certainly like the distance that these new technologies create. I’m talking maybe specifically about social networking stuff, but those distances create tensions and it’s those tensions that I'm interested in exploring. It can cause a lot of friction to be at a distance from something, and I’m not so sure that we’re so wired for it. It can be an unnatural state. There’s a vivid demonstration in the work of the uncanny valley, which I kind of suspected was there – meaning the forms and the graphics, and the ability to relate to them, doesn’t really bear a direct relationship to the progression of what year the game was made, perhaps more the mood of the times. It’s far easier to relate to some of the earlier and middle graphics than it is to relate to some of the more recent, somehow darker, cyborg graphics. I found myself really attracted to some of the graphics that were in the middle actually, they weren’t quite cute but they also weren’t quite as scary – there still seems to be some ‘hope’ in those graphics somehow? The tag line in the work is that the machines are losing repetatively. It’s supposed to be a joke that is repeated over and over and over again, which eventually becomes unfunny, but then becomes funny again."

Text by John-Paul Pryor