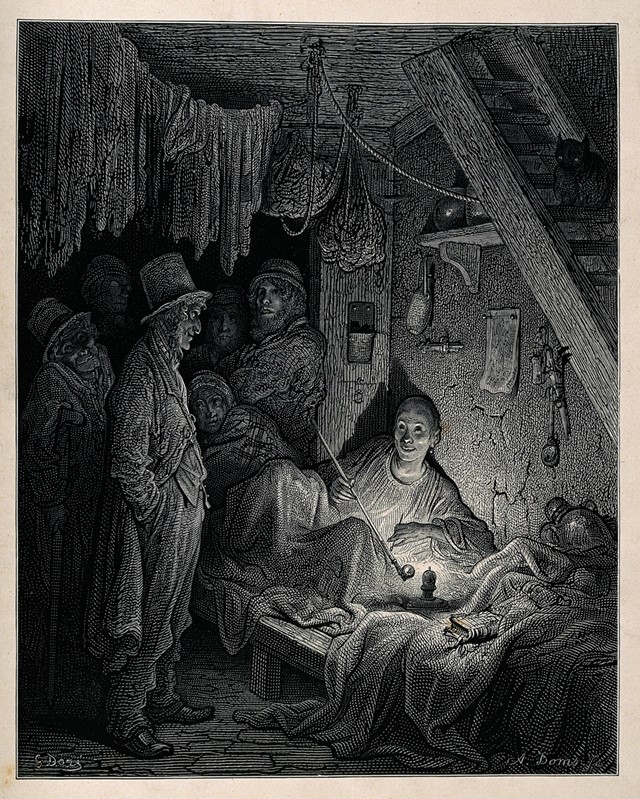

Here is a scene of gibbering shadows and sinister smiles. In Gustave Doré’s depiction of an East London opium den from 1872, we witness drug-induced oblivion from the corner of a subterranean lair. A Lascar, or Asian sailor, reclines on a rumpled

Here is a scene of gibbering shadows and sinister smiles. In Gustave Doré’s depiction of an East London opium den from 1872, we witness drug-induced oblivion from the corner of a subterranean lair. A Lascar, or Asian sailor, reclines on a rumpled bed with his long pipe resting on his knee, next to the lamp that will cook its contents. Above a grin, his eyes have turned completely black while those of his little cat, crouched above him on the stairs like a presiding goblin, burn demonically. Beyond, in the murky recess of the doorway, a mass of huddling men and women wait for their next fix.

This is typical of Doré’s vision of the city, realised across 180 engravings in his masterpiece, London: A Pilgrimage, the book he created with the writer Douglas Jerrold. Doré was a bestselling artist and engraver, who’d illustrated the work of Byron at only twenty-one, earning him the accolade of “the last Romantic”, and whose achievements include defining images for Don Quixote, and Dante’s Inferno. His London is every bit as hellish. Streets burst with bodies like an overcrowded prison. In a plate that inspired a painting by Van Gogh, Newgate’s inmates tramp in a ring in the yard: a vision of perpetual damnation. Everything is pressed in, airless and gloomy.

Indicating just how successful Doré was, he was paid the staggering sum of £10,000 a year to create this work. Yet like his peer Charles Dickens, he had social polemic on his mind. In fact, Doré’s opium den claims direct allegiance with that of the hallucinogenic opening scene in Dickens’ final novel Edwin Drood – both were inspired by the same Limehouse address.

It ranks amongst tens of compelling works included in High Society, a thorough and thoughtful show exploring drug culture across the ages. Doré’s mad hovel is very different from the genteel, peaceful dens depicted by artists in China at the time. While he excelled in his hard-hitting vision of the oppressed poor, his image of a drug-addled Lascar also plays squarely into Victorian prejudice about an ‘Oriental contagion’, as Chinese communities developed in city slums and Christian missionaries railed against the opium habits of the Far East.

High Society is at The Wellcome Collection until 27 February