As The Photographers’ Gallery celebrates Edward Steichen’s Condé Nast work of the 1920s and 30s, AnOther presents 10 key facts

Chances are that when you think of 1920s and 30s photography, you’re thinking of Edward Steichen (1879-1973). Way back when, in 1923, Vanity Fair described him as, “the greatest living portrait photographer.” Yet, young Edward, whose family had emigrated to the States from Luxembourg when he was a baby, started his career as a 15-year-old apprentice at a local lithographers’ firm in Milwaukee. As his teens progressed, Edward cultivated a talent for art. Here, to celebrate The Photographers' Gallery's new exhibition of Steichen's Condé Nast era works, AnOther looks back at Steichen’s life achievement in 10 key points.

1. One of Steichen’s first commissions was to photograph a drove of Wisconsin pigs for the lithography office. Later in life, he referred to such stock photographs as “useful images.”

2. On his way to Paris in 1901, Steichen met the influential photographer Alfred Stieglitz in New York. Stieglitz was impressed and over the next few decades commissioned Steichen for the critically acclaimed journal, Camera Work. Indeed, for much of 1900 and 10s, Steichen enjoyed a status as a somewhat avant-garde figure – someone who was a “paintre and fotographer”, living in Paris, and exhibiting in prestigious galleries.

3. After realising that he wouldn’t become the next Picasso, Steichen gave up painting in favour of photography. “I am personally willing," he said, "to avoid the discussion [of painting and photography] and calmly await development, feeling confident that even the most conservative critics will soon discover the superiority, at least in portraiture, of photography per se over the big majority of so-called portrait paintings.”

4. From the beginning of his career, Steichen maintained an equal interest in horticulture and photography. He won a gold medal from the French Horticultural Society in 1913.

5. In 1922, Steichen was 43, a divorced, heavily indebted father of two. His days as an artist, who had helped promote modern European art in America, appeared to be over.

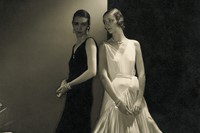

6. However, in 1923, salvation from poverty and obscurity came when Condé Nast offered him a job as Chief Photographer for Vogue and Vanity Fair. When Steichen accepted, it was assumed he wanted his work published anonymously or under a pseudonym. Fashion photography was regarded as a step down for him. But, almost anticipating Andy Warhol’s idea that art is only justified through commercial success, Steichen said, “There has never been a period when the best thing we had was not commercial art.”

“There has never been a period when the best thing we had was not commercial art" — Edward Steichen

7. During his time at Condé Nast, Steichen would slowly move away from softly focused images in the Pictorial style, which characterised much of his early work, to sharply focused, dramatically lit, and boldly composed portraits. In 1928, Steichen had fully moved to Modernism.

8. Photography Historian Joel Smith notes, “Steichen’s best celebrity photographs are realistic in a sense; when his sitters live up to the style in which they have been presented, one is convinced that their personal magnetism inspired the photographer’s vision of them, rather than the other way around.”

9. Steichen recalled the creation of the famous Gloria Swanson portrait: “Gloria Swanson and I had had a long session, with many changes of costume and different lighting effects. At the end of the session, I took a piece of black lace veil and hung it in front of her face. She recognised the idea at once. Her eyes dilated, and her look was that of a leopardess lurking behind leafy shrubbery, watching her prey. You don't have to explain things to a dynamic and intelligent personality like Miss Swanson.”

10. When the Second World War broke out, Steichen left his job at Condé Nast and worked for the US Navy as director of the Photographic Unit. Here he worked on the documentary The Fighting Lady, which won an Oscar in 1945. His post-war career was spent as the director of the Photography Department at MoMA, New York.

Edward Steichen: In High Fashion, The Condé Nast Years 1923 – 1937 at Photographers’ Gallery in London runs October 31 – January 18, 2015.

Words by Johan Deurell