What is the truth of Chechnya? David Monteleone's award winning photographs attempt to delve under the skin of an eternally shifting society

"Thank you". A simple expression, rarely posed as a question. But the viewer of David Monteleone’s exhibition Spasibo (Thank you) should be wary. For a keener eye and sharper ear are needed where a lens, seemingly clear, focuses on the twisted identity of Chechnya.

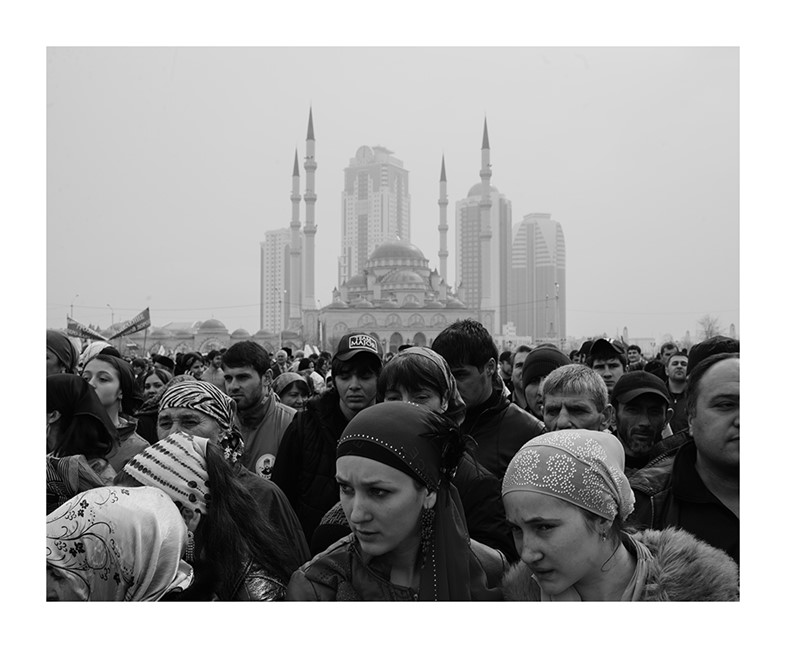

It is a country that drags with it a heap of tattered stereotypes, war-torn ideas of what constitutes a place and those who live in it. For many in the West, Chechnya is nothing but a place of conflict, its people either soldiers or victims. It is the purpose of the Foundation Carmignac and their Carmignac Gestion Photojournalism Award, to free countries like this, marked by moments in their past, so that they might live on in people’s minds as something present. Davide Monteleone, winner of the 2014 award and part-time Russian resident and long-time observer of Chechnyan life, believes this to be very important; "of course life goes on," he says with a shrug, "but the question is, how does life go on?"

His images demand a second glance. Each Carmignac award is about an idea rather than a series of images, and Monteleone’s exhibition asks us to "imagine what lies outside the pictures" that make up the portrait of a nation. For the viewer to "make their own story", drawing the separate images together with their own narrative thread. But, as in all politics, attention must be paid to what is not being said.

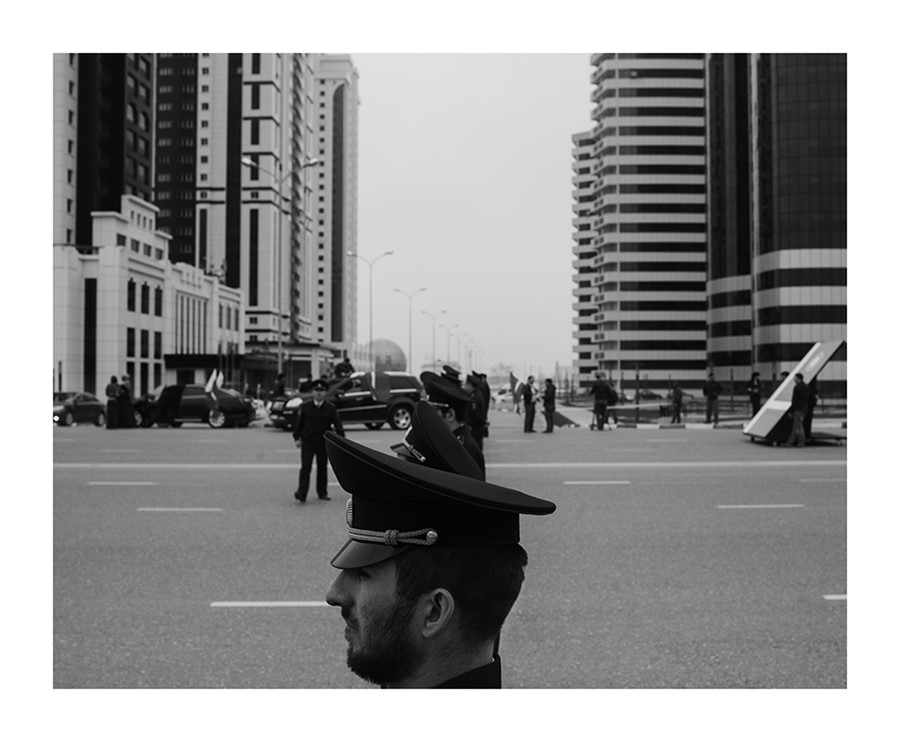

Each image is stalked by both the ghostly apparition of the country’s past and the shadowy hand of the state, embodied by the despotic ruler Razman Kadyrov, whose human rights violations are well documented. Monteleone seems at once in service to and in defiance of, Kadyrov’s brand of recently constructed nationalism – a strange "blend of Soviet ideals, Russian life, Islam and the cult of personality". The black and white images, hanging in the neat space of the Saatchi Gallery, carry the air of state-sanctioned authority. There is no sign of recent trouble, the cracks have been smoothed, all gaps covered over. But for those that want to see, are willing to look, Monteleone’s is a wry gaze that acknowledges what is being concealed, even as it reveals. Though taken with a leaden eye, it is all too easy to miss the point, as one thrilled Chechnyan official did on seeing the finished body of work and suggesting it should show in the newly built capital city of Grozny (literal translation ‘terror’).

"Each image is stalked by both the ghostly apparition of the country’s past and the shadowy hand of the state"

The famously resistant Chechnyan spirit, that has kept this nation in a state of constant tension with Russia, is echoed in Monteleone’s subtly subversive observations – the juxtaposition of a mosque and oversized Christmas tree (a gift from Moscow), a young actress dressed as a child bride (ghostly beneath her heavy white veil), or the group of soldiers lined up for a photo op, certain in the belief that they are in control of the image being created. There is prosperity here – a young bride before her Yves St Laurent trousseau, the gleaming buildings of Grozny. Monteleone references a quote passed to him by a friend in the mountains around Itum-Kali. "The Chechens are a combative people, difficult to conquer, easier to buy", and this deadpan documentation reveals the extent to which that same defiant spirit has been suppressed in the people themselves, the voice of resistance silent in the closed mouth of a young girl at a madrassa, the rebel spirit concealed in a seemingly empty mountain landscape. Here, in the gaps, is the price of this modern peace – the passive acceptance of a feudal tyrant whose regime strips away the notion of choice until the possibilities of the past are nothing but another ghostly memory.

Monteleone mirrors this game well. It seems that we are also given no choice but to engage with the propaganda-like images that present this state approved conception of Chechnyan identity. But this coercion is, of course, an illusion. We are free to pause between each image, a moment of contemplation that leads into the grey areas (for Monteleone, a defining colour of Chechnaya), the thread of our private narrative becoming a crack in the carefully presented façade that sheds just enough light to see things clearly, so that Monteleone’s neutral title begins to take on new meaning. "Spasibo Razman", he says, before asking, "Spasibo for what?"

Spasibo by David Monteleone is at Saatchi Gallery until November 3.

Text by Tamara Colchester