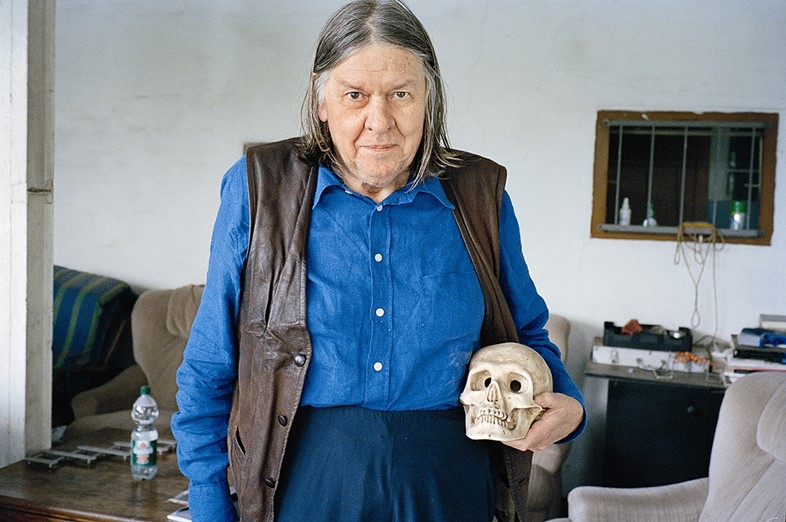

Author Chloe Aridjis visits filmmaker Werner Nekes, to delve into the world’s greatest collection of pre-cinematic objects

In the basement of a house in Germany, lie 500 years worth of optical instruments: experimental filmmaker Werner Nekes’s sprawling collection of pre-cinematic objects. Known for films including Beuys (1981) and Johnny Flash (1986), the director came across a thaumatrope – an optical toy considered the antecedent of the cartoon – in the 70s, and from there an obsession was ignited. Author Chloe Aridjis travelled to his home to delve into his fascinating world, the wellspring of all moving imagery.

Magic lanterns, zoetropes and perspective boxes, carved handles that cast shadows of historical silhouettes, games of anamorphosis where distorted scenes are brought into definition with the help of a special mirror or lens… In Werner Nekes’s home, one enters a world of Cartesian uncertainty where everything seems to be, or harbors, an illusion until proven otherwise.

I met Nekes in 2001 at a Magic Lantern Society convention in Birmingham, where he stood out in his black turtleneck and stern moustache. Over the years we fitfully stayed in touch, and in 2004 I went to Eyes, Lies and Illusions, an exhibition at the Hayward that comprised hundreds of items from his collection, probably the largest of pre-cinematic devices in the world. But my dream was always to see it in situ.

Nekes’s home is situated on a motorway in the small town of Mülheim an der Ruhr. He leads me down a steep flight of stairs, through a room crammed with film stock and video cassettes, and then into his vast compendium of marvels from the Renaissance onwards. The first he shows me is William Cheselden’s Osteographia, an anatomical tome from 1733 displaying life-size representations of bones. Drawn with the help of a camera obscura, many of the plates depict skeletons in animated poses. As with most objects in Nekes’s collection, it’s this play between interiority and exteriority, at work in both magic and science, that’s part of the wonder.

"In Werner Nekes’s home, one enters a world of Cartesian uncertainty where everything seems to be, or harbors, an illusion until proven otherwise"

He asks me what I’d like to see next. I look around, overwhelmed, with the sense that dozens of mechanical eyes stare back at me. I decide to pursue my own interest, magic lanterns. A large wooden one from Germany is the oldest in the collection, while his favourite is a Diableries brass lantern from around 1880. It is too fragile to handle – its images are hand painted on rhodoid and turn on a spool. Werner found it at auction in France – “Proust must have had such a lantern” – and claims only five were ever made.

Magic lanterns project images; perspective boxes keep theirs within. These little theatres of enigmatic depths often showed catastrophes such as the earthquake of Lisbon, and there’s a sense of a natural force, barely contained, bursting out of them.

So, where did it all begin? With thaumatropes, he smiles. In 1975, when Nekes was in Bilbao screening his films, he walked into a magic shop and asked the owner whether he had any “images that turn quickly”. The man brought out a handful of thaumatropes. These toys work on the principle of the afterimage and persistence of vision. Via a twirling motion, two sides of a painted disc merge optically, fusing into one: a parrot + an empty cage = an encaged bird; a woman in bed + a perching imp = an incubus. Although Nekes gave away his first thaumatropes to friends, something was triggered and he embarked on his passionate exploration.

Since my arrival, I’ve been aware of a sinister profile on a shelf, another eye. Nekes tells me to turn it fully around. A grimacing face comes into view, with a painted red mouth, a cold blue gem of an eye, a dangling earring. But it’s actually an ear from whalebone, he says, from around 1600, found at auction in Germany.

Of the value of his collection, Nekes says: “It has the grammar of everything that is possible.” I think back on Cheselden – bones form our own grammar, our verbs, subjects, prepositions, they dictate how we move through the world. Somehow Cheselden’s book, I realise, is emblematic of Nekes’ collection – for everything, on shelf or page, can be animated – and everywhere, there are reminders of mortality, haunting and beautiful memento mori.

Text by Chloe Aridjis