In the late 1960s my dad drove across America with some of his friends, and on the way through Mississippi they wanted to visit William Faulkner's old house, but they didn't know which town it was in, and no one would tell them...

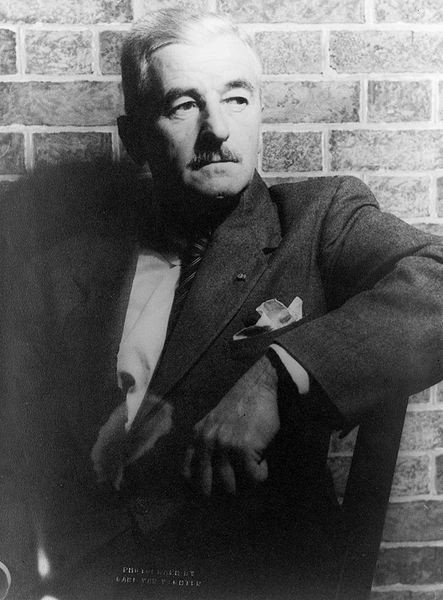

In the late 1960s my dad drove across America with some of his friends, and on the way through Mississippi they wanted to visit William Faulkner's old house, but they didn't know which town it was in, and no one would tell them. Then when they finally got to Oxford, in Lafayette County, they didn't know what street it was on, and no one would tell them that, either. The problem wasn't just that they had New York number plates on their car; it was also that even though Faulkner is the only Nobel prize winner ever to come out of Mississippi, toward their most famous son the locals felt mostly shame and resentment. Faulkner's imaginary Yoknapatawpha County, based on Lafayette, is feverish with “murder, rape, incest, suicide, greed and general depravity,” as the New York Times put it in his obituary, and it was Faulkner's novels that defined the entire south for generations of non-southerners. His exaggeration of his origins into a fictional universe so vividly grotesque that it begins to overwhelm reality connects him to another genius who died on this date, the German artist George Grosz.

“I had a blinkered hatred of the human race and I saw everything from the viewpoint of my little attic studio,” wrote Grosz about his Berlin paintings, which show purulent whores, crippled war veterans and gluttonous arms dealers waltzing joylessly through a gothic city of perpetual night. After Christopher Isherwood's novels and their spin-offs (such as Cabaret), it is Grosz's work that most informs our idea of Weimar Berlin. Read more about the era, though, as I have as part of the research for my second novel, and you discover that most recollections of Berlin in the 1920s also include beaches, rollercoasters, ice cream parlours, boxing matches, department stores, and modernist glass-and-steel buildings full of air and light. Grosz would never have denied that his work was a very selective caricature of the world in which he was raised. Nor would Faulkner. And neither, I think, would have wanted their perspective to be the only one that survived. But the sheer force of each man's vision has been enough to blot out nearly every other more moderate chronicle.

Late in their careers, Grosz went to New York and Faulkner went to Hollywood, but, with the exception of Faulkner's short story Golden Land, neither produced any worthwhile work in these more commercial, anonymous settings. They needed their homelands, because it was only their homelands that they really knew how to pillage and pillory for their art – a strange sort of loyalty. Perhaps, after all, it's not hard to understand why my dad didn't find the people of Oxford, Mississippi, too grateful to Faulkner for putting their town on the map.