A new show curated by Francesca Gavin, featuring work by the Chapman Brothers, is a discomfiting exercise in marrying horror and satire

There is something incredibly disquieting, even inappropriate, about the images that populate Toot Toot Tootsie Goodbye. But for once in the world of modern art, this hasn't come via wilful showboating or unnecessary nudity. The exhibition at Copenhagen’s V1 Gallery, curated by AnOther contributing editor Francesca Gavin, shows works by contemporary artists such as Jake and Dinos Chapman, Susan Hiller and Dionisis Kavallieratos that baldly depict and reference the darkest period of recent history: the rise of Hitler and National Socialism, World War II and the Holocaust.

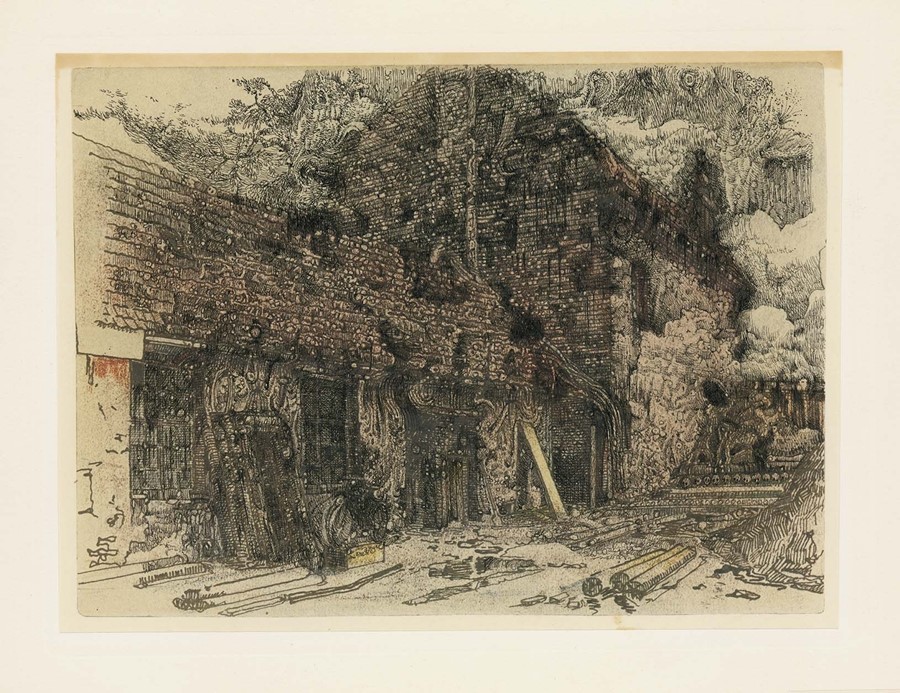

For many, the idea of a show like this is anathema. What good is gained from showing works featuring these 20th century bogeymen and their filthy deeds? Yet the power of the show comes from the treatment that these figures of horror receive at the hands of the artists. There is no fearful reverence – instead their ideals, their intentions and their figures themselves are reduced and ridiculed using the very blackest of satire. Kavallieratos shows a cringing soldier whose double handed heil is mirrored by his enormous erection; Fox has Hitler on the devil’s knee while a shrieking Ronald McDonald sprints away from hellfire; the Chapmans’ work is one of their infamous reworkings of Hitler’s own mediocre sketches. Together it is a collection that makes one snigger and then think, undermining the potency of the evil while never allowing the viewer to forget its existence.

"Together it is a collection that makes one snigger and then think, undermining the potency of the evil while never allowing the viewer to forget its existence"

Here, in advance of the show’s opening, we speak to curator Gavin about the victory of satire over evil, and what makes the events of the 1940s so powerfully resonant now.

What was it that inspired you to pull together this show at this time?

The exhibition was conceived as a response to the work of Hesselholdt and Mejlvang – a female duo working largely with installation and ceramics who asked me to curate something alongside their solo show at V1 Gallery in Copenhagen. Their work often explores ideas around politics and the rise of the far right. We met and they showed me some of their research into contemporary neo-Nazis and in particular these shrine-like images of their collections of guns and Nazi memorabilia. I felt that it was a very timely and very interesting subject to be responding to. I had curated a collection in Berlin a few years ago and had come across some works by Dionisis Kavilleratos and Dennis Rudolph that I found really interesting, unsettling and had always had in mind to do something with them.

What is it about this moment in time that requires a show recalling the darkest elements of WW2?

No one seems to be talking enough about what is happening in Europe and Russia at the moment – the horrific rise in anti-Islamic and anti-semitic sentiment, violent responses to homosexuals and transsexuals. I was very aware how elements of the far right were exploiting the current recession for their own ends. It immediately brought to mind the rise of National Socialists in Germany in the 1930s and how those circumstances were not just time specific. That genocide and violence can happen again and we must always be wary as a wider populace so it doesn’t.

Laughter and satire were needed at the time of the Nazi atrocities to undercut the power of the enemy and maintain morale. How is it still relevant to laugh at these things today, when the perpetrators have been defeated yet their crimes remain?

I think it is even more relevant now to address the power of the myth of Hitler and Nazis with humour than in the past – though I’d point out that in this exhibition humour is strongly balanced with some exceptionally disturbing works of horror. I have always been a huge admirer of Mel Brooks’ approach to WW2. If you remove the potency of the symbol, the mythic character, this sense of something taboo – and therefore for some people attractive – it becomes less powerful. I think Brooks spoke about it eloquently in Der Spiegel, “You can laugh at Hitler because you can cut him down to normal size... Of course it is impossible to take revenge for 6 million murdered Jews. But by using the medium of comedy, we can try to rob Hitler of his posthumous power and myths.”

Is there an image in the show that best defines how you feel about this moment in art and cultural history?

The humour in the exhibition (from Dionisis Kavilleratos and Neal Fox), the disturbance (from Dennis Rudolph, Jake and Dinos Chapman and Stephen Dunne) for me personally all is centred around Susan Hiller Brandenburg Suite – an offshoot from her J Street Project. She photographed hundreds of German street signs with names like Judenstrrasse, Judengasse, Judendorf (Jews Street, Jews Alley, Jews Village) - highlighting a community that was completely wiped out. All the streets in Hiller’s images are empty and devoid of people. I think it is one of the most poetic and haunting reflections on the Holocaust.

Who are your favourite artists who were working and commentating at the time of WW2?

My exhibition is focused on contemporary artists, but looking back in time I’m a huge admirer of George Grosz who did an incredible painting in 1944 titled Cain, or, Hitler in Hell, of Hitler sitting on a piles of bones in an apocalyptic landscape. Erwin Blumenfeld did a photomontage of Hitler with a skull in 1933 that is impossible to forget. Also I think Charlie Chaplin’s 1940 film ‘The Great Dictator’ is an incredible artwork.

Toot Toot Tootsie Goodbye curated by Francesca Gavin runs from Sept 13 – Oct 14 at V1 Gallery, Copenhagen.

Text by Tish Wrigley