Nicholas Kirkwood is universally acclaimed as the most talented shoe designer of his generation. Often described as Manolo Blahnik’s legitimate heir, he started his career by working with Philip Treacy...

Nicholas Kirkwood is universally acclaimed as the most talented shoe designer of his generation. Often described as Manolo Blahnik’s legitimate heir, he started his career by working with Philip Treacy. His unique creative vision was acknowledged very early on by such iconic figures as Isabella Blow, Cecilia Dean, Franca Sozzani, and André Leon Talley. The recipient of numerous awards, he has collaborated with such major fashion voices as Rodarte and Erdem, and now appears on his own as a leading figure of contemporary fashion design.

How would you connect fashion to elegance?

Originally it is more of a personal trait, something people can actually have in a way they behave. Someone could be walking through with the most ridiculous outfit on and still somehow have an air of elegance about oneself. But it certainly is a word that has been appropriated by fashion as the propriety designers want their clothes to possess.

What is the role of history and art history in your conception of fashion?

Fashion loves to reference the past. I think that it’s somehow a shame: somebody first came up with the first mini-dress, and then it wasn’t a reference to something pre-existing. So why can’t we be original anymore? Why should we say that everything has already been done? Maybe certain things haven’t be done before… Like the pump: the pump didn’t grow on a tree, with the apple. Someone invented it. It is still possible to create newness without referencing history. However, for the consumer and for many designers it is more straightforward in the way it is talked about: it is more easy to talk in a referential way, to say “my inspiration was X, Y and Z”. People need to have that kind of historical reference. In architecture, things are totally different: architects completely look down on references past, and the reinvention of them, whereas in fashion, it’s pretty much all that happens.

"Why can’t we be original anymore? Why should we say that everything has already been done?...The pump didn’t grow on a tree, with the apple"

Would you describe fashion as a language and a discourse, as Barthes did?

It’s an applied art. And as such, it is the language of interpretation. Language is also something that exists across the world, but which experiences the impact of specific locations. American designer can be seen as very different from an European designer or a Japanese designer. It comes back to the interpretation of your city, of your friends, and your culture. You still see it now, even if the world if becoming smaller due to new technologies.

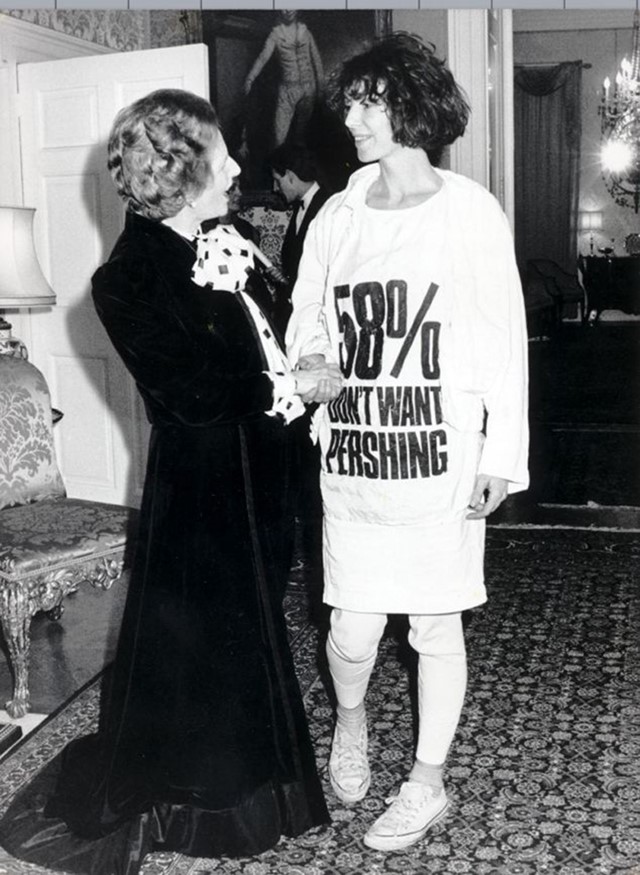

The word "intellectual" was coined in a time of great political distress. Does fashion have a political role? And in which way?

Fashion in most cases tends to be a reaction to a particular circumstance. In times of affluence, like the 1980s, it’s about excess: the shoulder pads got wider, the hair got bigger. Then there’s a financial crash, and, in the 1990s, everything became minimal. It became about not showing off in the same way. After the war, it was the exact problem. There were materials problems, and in the 1920s the dresses became very straight, because there was a lack of getting certain materials. Then there are other circumstances, and other forms of reactions, like the punk rock: it was a reaction to political circumstances, in an almost aggressive way. It became political, in the sense that it stood for a cause.

How would you relate the concept of "fashion" to the one of "style"?

Fashion is trend ultimately. Trends are very different to style. People loved perms in the 80s. It was definitely a trend, but was it stylish? I probably thought so at the time, but trends end up not belonging to style. You expect style to be continuous, and timeless in a way. Fashion is about evolving: if it didn’t have that excitement about it, everybody would be trying to be elegant the whole time, and perhaps that could be a bit boring.

What does fashion have to do with intellectuality ?

A certain type of fashion designers tries to intellectualise what they’re doing, in the way they promote their designs. When you look at certain brands, there is a kind of intellectual aura about it, but often it’s down to PR and the way the show is presented. Fashion is about the product, but it is also about the experience. You can show the same simple product in a very different way on different types of models, with a different music and a completely different spirit, and make it not feel so intellectually superior. Some people want to buy fashion, because it has a sense of glamour, others care for the intellect.

"Some people want to buy fashion, because it has a sense of glamour; others care for the intellect."

Your designs are full of fantasy. What is the role of imagination within your work and your conception of fashion?

There has to be an element of imagination. There are actually two forms of imagination: one is coming up with the design, and the other with the act of acquiring a piece of clothing. We need fashion to have an element of fantasy within itself – it is, after all, a form of escapism. It’s like watching a movie or reading a book, to get away from the real world. The real world is not that exciting or that happy… People can express themselves through the clothes they buy. They can become somebody else. Without the fantasy, it would only be utilitarian, and not nearly as attractive.

There is a sense of structure within your work. What is the role of architecture in your designs?

When I was ten years old, I was really attracted by the idea of being an architect, and conceiving actual buildings. Then I found out that it was a seven-years course – almost my entire life! But I am still fascinated by the concept of architecture, even if I didn’t study it. When I started designing shoes, and also when I worked for Philip Treacy, I was confronted to very sculptural objects. Shoes and architecture didn’t seem such an odd marriage. At the beginning, when talking about my products, I started using the expression “architectural shoes”. And then it spread around, and a few people started using it as well. All of a sudden, all shoes were architectural. Then I stopped using the word because it seemed such a cliché. I tried to come up with other words: “is it sculptural”, “is it this”, “is it that”. But at the end “architectural” was the fine word to use. That’s what I do. There is some very architectural element about it – there is a tension string, so to speak. The curve, the line, the angles, all of it is close to the structure of a bridge, if not of a building in itself.

In two weeks Donatien will be interviewing the artist Alexandre Singh.